Ancient Persian Art

History, Characteristics of Achaemenid,

Sassanid Cultures.

MAIN A-Z INDEX

|

Ancient Persian Art |

|

DIFFERENT FORMS OF ARTS |

Art of Ancient Persia (from 3,500 BCE)Contents • Persian

Art: Introduction (3500 BCE - 1700 CE) What is Ancient Persian Art? The art of ancient Persia includes architecture, painting, sculpture and goldsmithing from the early kingdom of Iran in southwest Asia. The term "Persia" derives from a region of southern Iran previously known as Persis, or Parsa, which itself was the name of an Indo-European nomadic people who migrated into the region about 1000 BCE. The ancient Greeks extended the use of the name to apply to the whole country. In 1935, the country officially changed its name to Iran. From its earliest beginnings, ancient art in Persia was a major influence on the visual arts and culture of the region. |

Gold Chariot from the Oxus Treasure (c.600-400 BCE) A collection of some 180 pieces of gold and silver metalwork from the Achaemenid civilization of Ancient Persia. The chariot comes from the region of Takht-i Kuwad, Tadjikistan. |

|

|

Persian Art: Introduction (3500-1700 BCE) Persia, one of the oldest countries in the world, and one of the earliest civilizations in the history of art, occupies the Persian plateau, bounded by the Elburz and Baluchistan mountains in the north and east. In ancient times, during the first Millenium BCE, Persian emperors like Cyrus II the Great, Xerxes and Darius I extended Persian rule into Central Asia and throughout Asia Minor as far as Greece and Egypt. For much of Antiquity, Persian culture intermingled continuously with that of its neighbours, especially Mesopotamia (see: Mesopotamian art), and influenced - and was influenced by Sumerian art and Greek art, as well as Chinese art via the "Silk Road". For more about this, see also: Traditional Chinese Art: Characteristics. |

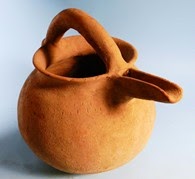

Luristan Pottery Vessel (c.1500 BCE) Ancient pottery from Western Persia. Hixenbaugh Gallery of Ancient Art. New York. See Pottery Timeline. |

Early Persian artworks include the intricate ceramics from Susa and Persepolis (c.3500 BCE), as well as a series of small bronze objects from mountainous Luristan (c.1200-750 BCE), and the treasure trove of gold, silver, and ivory objects from Ziwiye (c.700 BCE). Most of this portable art displays a wide variety of artistic styles and influences, including that of Greek pottery. Items of ancient Persian art are exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) and the British Museum, London. Achaemenid Era (c.550-330 BCE) The first upsurge of Persian art occurred during the Achaemenian Dynasty era of the Persian Empire, under the influence of both Greek and Egyptian art. Persian art was exemplified in a series of monumental palace complexes (particularly at Persepolis and Susa), decorated with sculpture, especially stone reliefs, and the famous "Frieze of Archers" (now in the Louvre Museum in Paris) created out of enameled brick. The city gate at Persepolis was flanked by a pair of huge bulls with human heads, while in 515 BCE, Darius I ordered a colossal relief and inscription to be carved out of rock at Behistun. The sculpture portrays shows him vanquishing his enemies watched by the Gods. Persian sculptors influenced and were influenced by Greek sculpture. Other artworks from this period include dazzling gold and silver swords, drinking horns, and intricate jewellery. See also the History of Architecture. |

|

Parthian Era (c.250 BCE) Persian art under the Parthians, after the death of Alexander the Great, was a different story. Parthian culture was an unexciting mixture of Greek and Iranian motifs, involving visible on monuments and in buildings decorated with sculpted heads and fresco wall painting. Sassanid Era (226-650 CE) The second outstanding period of Persian art coincided with the Sassanian Dynasty, which restored much of Persia's power and culture. Sassanid artists designed highly decorative stone mosaics, and a range of gold and silver dishes, typically decorated with animals and hunting scenes. The biggest collection of these eating and cooking vessels is displayed at the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. As well as mosaic art and metalwork, frescoes and illuminated manuscripts were two other art forms which thrived during this period. In addition, crafts like carpet-making and silk-weaving were also strongly encouraged. Persian carpets and silks were exported as far as Byzantium (present-day Istanbul) to the west and Turkestan to the east. However, the most striking relics of Sassanian art are rock sculptures carved out of steep limstone cliffs (eg. at Taq-i-Bustan, Shahpur, Naqsh-e Rostam and Naqsh-e Rajab) which depict the victories of the Sassanid leaders. The influence of Sassanian artists extended to Afghanistan (a Persian colony of the time), where excavations at monasteries at Bamian have revealed frescoes and huge Buddhas. The Sassanian Empire collapsed after being defeated by the Byzantine Roman Emperor Heraclius. Persia Under Islam After being overrun by the Arabs in 641, Persia became part of Islam and its visual arts developed according to Islamic rules. One of these - the ban on three-dimensional portrayal of living things - led to an immediate decline in Persian sculpture and forced fine art painting to become more ornamental and adopt the flat traditions of Byzantine art. However, in decorative art, like ceramics, metalwork and weaving continued to flourish, especially from the time of the Abbasid Dynasty (750-1258) in the eighth century. Ornamentation of Islamic temples like the Mosque of Baghdad (764), the Great Mosque at Samarra (847), the tenth-century mosque at Nayin, the Great Mosque at Veramin (1322), the Imam Riza Mosque at Meshad-i-Murghab (1418), and the Blue Mosque at Tabriz. Mosaics and other decorations were widely used in mosques and other buildings. Coloured roofs, using ceramic tiles in blues, reds and greens were also a popular part of Persian architecture. Illumination and Calligraphy With the decline in figure drawing and figure painting, one popular Islamic art form which developed in Persia was Illumination - the decoration of manuscripts and religious texts, especially the Koran. Iranian illuminators were active during the Mongol takeover of the country during the late Middle Ages, and the art of illumination reached its heyday during the Safavid Dynasty (1501-1722). The copying of religious works also stimulated the development of ornamental writing like calligraphy. This grew up during the eighth and ninth centuries, roughly concurrent with the era of Irish illuminated manuscripts and became an Iranian speciality. Painting Painting was regarded as an important art under Islam. Around 1150, several schools of religious art emerged which specialised in the illustration of manuscripts of various types, all illustrated with miniature paintings. This art form, in combination with illumination, grew into a significant artistic tradition in Iran. The most famous Persian miniature painter was Bihzad, who flourished at the end of the fifteenth century, becoming the head of the Herat Academy of Painting and Calligraphy. His landscape paintings were executed in a realistic style using a vivid colour palette. Among his pupils were several noted painters of the day, including Mirak and Sultan Mohammed. Bihzad's paintings are represented in the University Library at Princeton, and the Egyptian Library in Cairo. Other painting styles, such as mountain-scapes and hunting scenes became popular during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries with Baghdad, Herat, Samarqand, Bukhara and Tabriz becoming the main art centres. Later, portrait art became fashionable. From the late 1600s, Persian artists imitated European painting and engraving, leading to a slight weakening of Iranian traditions. |

|

|

Ancient Persian Art & Culture: Summary Archaeology Surviving remains of ancient Persia were first brought to notice by Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela in the 12th century, and subsequently by Sir John Chardin (l7th century), Karsten Niebuhr (18th century), Sir Henry Rawlinson and Sir Henry Layard (19th century) and by the many travellers to Persia. E. Flandin and P. Coste were commissioned to make drawings of these remains in 1839. Investigation began only in 1884-86, when M. and Mme M. Dieulafoy settled in Sus a (identified by W. K. Loftus) where J. de Morgan began systematic excavations in 1897; this work was carried on by R. de Mecquenem and later by R. Ghirshman, while the Oriental Institute in Chicago and the Department of Iranian Antiquities concentrated their efforts on Persepolis. Geography Persia assumed the name of "Iran" under the Sassanids. It is bounded by Armenia, the Caspian Sea and Russia to the north, Afghanistan to the east, the Persian Gulf to the south and Iraq to the west. The country is made up of a very high plateau with a central salt desert. To the west this plateau runs into the mountains of Armenia and, along the eastern side of Mesopotamia, matches the plateau of Asia Minor which borders Mesopotamia to the north-west. These two plateaux, cut by small valleys, form the extreme edges of the central Asian plateau known as the 'great steppes'. The empire of the Achaemenid Persians extended far beyond these boundaries, stretching from the Indus to the Aegean Sea and the Nile. History Civilisation grew up in this part of the world at a very early date. Its existence during the age of Neolithic art, possibly from the 5th millennium, is borne out by the excavated sites at Tepe Hissar, Tepe Sialk (pre-'Ubaid culture) and, a little later, at Tepe Giyan ('Ubaid culture). The excavation of Susa, the capital of the country of Elam bordering on lower Mesopotamia, has shown that the growth of this civilisation was to be closely dependent on the development of Mesopotamian civilisation.

The great Indo-European migrations of the 3rd millennium brought Aryans, on their way to India by way of Turkestan and the Caucasus, to the Iranian plateau. Some of them intermarried with the people of the Zagros Mountains, where they took control; soon after, they swept down into Babylonia, and this was the beginning of the Kassite domination that was to last almost until the end of the 2nd millennium. (See also: Hittite art 1600-1180 BCE). The Assyrians, in a few centuries, were to reverse the situation. The Medes, a young Iranian warrior tribe like the Scythians and brought up in their tradition, had selected Ecbatana as their capital, while the Persians, members of the same race, descended the slopes of the Iranian plateau. About the 9th century B.C. the Assyrians began to move southwards and came into conflict with the Medes and Persians in the Zagros Mountains; in the 8th century Sargon smashed the alliance of Median leaders. Phraorte then became the leader of the Medes, Mannaeans and Cimmerians, and conquered the Persians. The Scythians, who had taken control of Media, were governed by Cyaxares; he reorganised the army and, following his alliance with Nabopolassar, founder of the Chaldean dynasty in Babylon, and with the help of nomadic tribes, he destroyed Nineveh in 612, thereby avenging the Assyrian sack of Susa in 640. Prior to the Scythian invasion the Persians had established a sovereign state under Achaemenes, which was to be reunited under Cambyses I; his marriage to the daughter of the Median king produced Cyrus, who conquered Media in 555, then Lydia in 546 and lastly, in 538, Babylon. He was succeeded by Cambyses in 529. Cambyses had his brother Smerdis put to death, conquered Egypt and proclaimed himself king and conquered Ethiopia, but because of the Phoenician sailors' lack of cooperation, he was unable to reach Carthage. On his death a pretender claiming to be Smerdis stirred up the people. Darius I deposed the usurper, crushed the rebellion and launched out to conquer India (512). Later, turning to the north and Europe, he marched as far as the Danube. The rest of the story belongs to Greek history: the Ionian rebellion, the burning of Sardis (499), the fall of Miletus (494) and finally the first Persian War and the battle of Marathon (490). Darius, who had recognised his son Xerxes as heir to the throne, died at the age of thirty-six. None of his successors came near to matching his greatness,with the exception of Artaxerxes II (Mnemon) who signed the peace of Antalcidas (387), a compensation for Marathon and Salamis. He was the last of the great kings; Artaxerxes III (Ochus) and Darius III (Codamannus), the ill-starred opponent of Alexander, were both unfit to rule.

Early Art Little has survived of the art of the Medes,

and the most important remains come from the Sakkez treasure found

to the south of Lake Urmia. It could just as well be the treasure of a

Scythian king. The objects belonging to it can be divided into four groups

which reveal the various influences affecting Median art: in the

first group can be put a typically Assyrian bracelet adorned with

lions carved in relief; the second group, identified as Assyro-Scythian,

includes a breast-plate on which a procession of animals is making its

way towards a cluster of stylised Sacred Trees. In actual fact, except

for one or two animals in the Scythian style, this shows entirely Assyrian

influence. The last two groups are Scythian (scabbard and dish

decorated with Scythian motifs, notably the lynx) and native (which

can be related to bronzes like those from Luristan). Achaemenian art, the youngest art of the ancient Orient, covers two centuries (from the middle of the 6th to the middle of the 4th). Examples can be seen in the ruins of Pasargadae, Persepolis and Susa. |

|

|

Architecture Ancient Persian City of Pasargadae This was the first settlement on the plateau for which Cyrus was responsible. The palace and various other buildings were set among gardens, and the many columns, surmounted by bulls' heads, show that the ideas behind the apadana were already in full force. Pasargadae can be described as the forerunner of Achaemenian architecture, but the terrace near Masjid-i-Sulaiman, with its gigantic walls and the ten flights of stairs leading up to it, can be attributed to the Persians and to a period prior to the building of Pasargadae and Persepolis. Fire Temples At Pasargadae there is also a fire temple.

These temples were square towers, built of well-bonded stone with mock

loopholes and windows in dark materials; inside, the sacred fire was kept

alight by the Magi, who belonged to a Median tribe specially trained in

the study and practice of religious ritual. At one time these buildings

were thought to be 'towers of silence'. Similar structures can be found

near Persepolis and at Naksh-i-Rustam, along with four-sided monuments

having ornamental bas-relief battlements, that have been identified as

fire altars. Not far from Pasargadae, at Meshed-i-Murgad, stands the tomb of Cyrus, a rectangular building set on a base of seven stone-courses, with a gabled roof made of flat stone slabs. It can be compared with monuments in Asia Minor. At Naksh-i-Rustam, near Persepolis, are the royal rock-tombs standing one beside the other. The tomb of Darius Codamannus at Persepolis was never finished. The tombs are hollowed out of the rock on the pattern of the tomb of Da-u-Dokhtar in the province of Fars. The architects carved from the rock itself an imitation of a palace facade with four engaged columns, crowned by 'kneeling bull' capitals which support an entablature decorated with a Greek moulding; above this is carved a line of bulls and lions, on which rests a dais held up by Atlantes; the king, turning towards a fire altar, stands on steps beneath the emblem of Ahura Mazda whose face is inside the circle. Private tombs have been discovered (like the one at Susa) in which a woman of high rank, adorned with jewels, was laid in a bronze receptacle. Ancient Persian City of Persepolis It was here that the Achaemenian genius developed to the full. The barracks and citadel were built on a mountain overlooking a wide plain in the direction of Shiraz. The lower slopes were levelled off for an esplanade on which a virtual city of palaces was built. Although excavations have now uncovered almost all the buildings, we still have no very clear idea of the purposes for which they were intended, although it would seem that the buildings in question are almost exclusively state or ceremonial edifices. From the walled esplanade a great stairway with a double ramp leads down into the plain; opposite the highest landing are the propylaea of Xerxes, a massive four-sided structure open at each end and along the sides and decorated with colossal human-headed winged bulls. Around the entrance, spaces left empty with regular hollows cut out of the rock were intended for terrace gardens. What is left of the palace is a veritable skeleton structure of doors and windows hewn from great blocks of stone that served as supporting props for walls that have long since vanished. Here the Egyptian gorge was used, and the king was portrayed on the lateral blocks of stone inside the doorways. On the right side a stairway, decorated with bas-reliefs, led to the apadana of Darius and Xerxes. The apadana, used as an audience chamber, was a typically Achaemenian structure. Its roof was supported by columns about seventy feet high-fluted, slender shafts that were mostly set on a bell-shaped base and were crowned by typically Achaemenian capitals like the one from Susa which is now in the Louvre. The lower part of these eighteen-foot-high capitals was made up of volutes, like C's set back to back, which supported the main part of the capital - the forequarters of two kneeling bulls, joined together. Beams rested on the saddle and in turn supported the larger beams of the roof so that some weight was taken by the bulls' heads. The apadana at Susa had thirty-six columns and covered an area of almost two and a half acres. This chamber at Persepolis had the same number of columns and was surrounded by a single peristyle that had two rows of six columns on three sides. Ancient Persian City of Susa The old royal cities continued to be important alongside the new capitals. At the ancient Elamite capital of Susa, on a hill, Darius I built his winter residence, with its vast apadana which was restored by Artaxerxes II (Mnemon). It was explored by M. Dieulafoy, who retrieved some of its glazed ornamentation, and then by J. de Morgan in 1908, who uncovered the building's plan by tracing cuttings in the ground pavements (made of a sort of concrete composed of chalk and pounded baked clay) which corresponded to the baked-brick walls dating from 440. The palace was planned on similar lines to the one in Babylonia, with chambers arranged around a rectangular court. Plastic Arts (Sculpture) The plastic arts were primarily devoted to the ornamentation of the palaces. Bas-reliefs formed the main part of the Persepolis ornamentation: the double stairway which led on to the terrace and into the palace chambers was decorated with two kinds of bas-relief. The motif of the lion attacking a bull, a familar device since the earliest period of Mesopotamian art, appeared on the triangular panels of the balustrades; elsewhere, the king 'in majesty' was found. On a dais shaped like a throne, a colossal prototype of the royal Persian throne (the Peacock Throne), the king sits in a great chair. Beneath the dais, lines of figures are carved, whose dress indicates that they belong to the various satrapies. The second type of bas-relief depicts processions of guards, courtiers and tribute-bearers. The artist has taken immense trouble to differentiate the characteristic features of their dress. The Persians wear a single or embattled tiara and long robes whose wide sleeves are adorned with symmetrical folds in imitation of drapery (a concession to Greek influence) but of a completely uniform treatment. Over one shoulder they carry a quiver holding a bow and arrows. The Medes, wearing caps, have a short tunic, and trousers, entirely free of folds, caught in at the ankle. They carry daggers with scabbards of the same shape as those of Scythian origin. The tribute-bearers are distinguished more by the nature of their gifts than by their costume and are preceded by a chamberlain. Along the great routes of the empire, even in the most outlying regions, artists carved bas-reliefs in the king's glory, like the one carved on the rock at Behistun, which accompanies Darius' proclamation and portrays him as a conqueror in an already familiar pose, with the defeated enemy beneath his foot. Graeco-Persian reliefs from the end of the 5th century have been discovered in the region of Dascyleium in Bithynia, depicting a procession of men and women on horseback and a Persian sacrifice with two priests (Magi), the lower half of their faces veiled, carrying a mace in their hands, nearing an altar, with the heads of a ram and a bull on a brushwood stake at their feet. At Susa, glazed bricks, copied from Babylonia, took the place of the marble ornamentation of Persepolis. The Achaemenians, howewer, used a different method from that of by their teachers. Instead of clay they used chalk and sand. The bricks were first baked in a moderate heat and then the outline of the figures was added in blue glaze and the bricks were returned to the oven; finally the areas outlined in blue were filled in with chosen colours and received one last baking to complete the process. The ornamentation of the staircase balustrades at Susa drew its inspiration from the Theban tombs with their superimposed lotus flowers, and from Aegean art with its alternating volutes. The gates were adorned with lions, their coats dappled grey-green or blueish, set in a framework of zigzags and palmettes interspersed with scallops and rosettes. The palace walls were embellished with mythological beasts, whose origins can be traced back to Babylonia, with scallop-edged wings and breasts coloured alternately yellow and green. Elsewhere, as at Persepolis, there were robes of lavish embroideries on material of white or yellow ground, adorned with three-towered castles and eight-pointed stars, the folds indicated in dark colours; these garments had wide yellow or purplish-brown sleeves; the shoes of the guards were yellow, their quivers made of panther skin and their hair held back by a bandeau. Between the gateways sat sphinxes wearing the horned tiara head-dress, their heads turned to look behind them in an inscrutable attitude but one which adds a great decorative appeal to this motif which recurs on the seal of Darius' chancellery, where the sphinxes turn to face towards each other. Minor Arts Metal-work, of the utmost importance to an equestrian people, suffered no decline under the Achaemenids. Bronze was used for the facing of certain parts of buildings, such as doors. For work in gold and silver an especially elaborate technique was employed, with silver dishes in repousse (foreshadowing Sassanian plate with its rosette and boss-beading ornamentation), angled rhytons whose bases are formed by the head of a goat or an ibex, vases with handles ending in an animal's head or else made to represent an animal's body (like the two handles of the same vase, one of which is in Berlin and the other in the Louvre, depicting a winged silver ibex incrusted with gold), a triangular stand from Persepolis composed of three roaring lions, the realistic treatment of which contrasts with that of the bronze lion found at Susa, comparable in pose to the lion from Khorsabad but far more stylised and suggestive of the monsters of the Far East. Jewellery shows a wide variety of influences. Some ornaments from the Oxus treasure in the British Museum - gold plaques, bracelets and rings - indicate the same Scythian influence that can be found in other treasures. Gems from the Susa sepulchre - crescent-shaped earrings decorated with coloured stones set in gold, and bracelets with no clasp but tipped with a lion's headand incrusted with turquoise and lapis lazuli, illustrate a technique which was to be adopted by the 'barbarians'. (See: Jewellery: History, Techniques.) Achaemenian glyptics surpassed in refinement anything hitherto known: one of the finest intaglios shows the king in his chariot out hunting with bow and arrow, his horses at full gallop. A plaque used as a mould for inlaid gold leaf has been found, as well as a small head of extraordinary delicacy - all that remains of a statue, for after the looting by Alexander's soldiers statuary, like everything else, survived only in a mutilated condition. On the obverse side of the gold coins called darics, the Achaemenid kings, kneeling on one knee, are depicted as archers. |

|

|

Ancient

Persia: Art and Architecture Greek civilisation owed a great deal to that of Asia Minor; at a very early date, contact between the two was established along the shores of the Aegean. This lasting contact developed, little by little, into a formidable struggle against the Persian empire, whose history was closely linked with an Oriental civilisation that the West was for ever to be confronted with and that it was never able to escape. The Medes and Persians were part of the tide of Aryans who, taking advantage of the upheaval produced by the Indo-Europeans throughout the entire ancient world, came to settle on the Iranian plateau. The Medes, like both the Cimmerians - who came from Thrace and Phrygia - and the Scythians, were a race of horsemen possessing no other riches beyond objects that could be carried with them, such as weapons, metal vessels and ornaments. Median art, of which the Sakkez treasure is the main example, combined the influence of the Medes' northerly neighbours the Scythians with that of their opponents the Assyrians. The Persians, who settled farther south, spent some time, however, in northern Iran where they came under Median domination. Their art, consequently, from the time they were firmly established on the Persian plateau presents an everlasting dualism springing from this mixture of influences, from the north and from the south with its echoes of Mesopotamian traditions. The union of these two basic factors was strengthened by the marriage of the Persian king Cambyses to the daughter of the Median king. It also incorporated elements of foreign arts in the expansion of that vast empire that one day was to extend from the Indus to the Nile; thus a composite art was created which was typically Achaemenid but of which only a few works, created for the court, remain. The Achaemenids - The Builder-Kings When Cyrus captured Babylon in 538 and

the Achaemenid Dynasty took the place of Babylonian rule, the capitals

of the new empire were brought farther east to the Persian plateau and

to Susa, bordering on the plains of lower Mesopotamia, thus reducing the

great cities of the Tigris and Euphrates basin to the state of mere satellites.

This kind of upheaval was inevitably bound to carry the art of this region

in new directions. |

|

|

Art and Symbolic Meaning When we come to consider the number of columns generally used in buildings we find that it is always connected with the number 4 and its multiples: 4, 8, 12, 16, 36, 72,100. It could very well be that here as in Mesopotamia we are faced with a law that obeys the 'symbolism of numbers'. From the very earliest times, the Sumerian goddess Nisaba was thought to be versed in the meaning of numbers, and the Tower of Babel and the Great Temple provide us with typical examples of the architectural application of sacred numbers. The preponderance of the number 4 at Persepolis corresponds to some new conception; did it perhaps symbolise the four elements of fire, air, water and earth? The number 12, that was soon to be endowed with a quite special significance, was also used a great deal. In more ways than one the influence of Europe was already making itself felt among the Persians. This is borne out if we look at certain themes such as the king battling with a fantastic beast, where it is now no longer a question, as it was with the Assyrian king, of exalting his bravery in a hunting exploit: the king is at grips with a demon, plunging his dagger into its body. Now it has become a conflict between the spirit of good (Ahura Mazda) and the spirit of evil (Ahri-man). This theme came to symbolise the victory of the Aryan god of light, who was depicted in the act of killing a dragon. It seems likely, nevertheless, that the Persians were responsible for the introduction of a new type - the 'horseman-god' - who became an accepted iconographical figure; he recurs in Egypt in Coptic art with the god Horus on horseback (in Christian iconography identified with St George) crushing the crocodile. This conception of the conflict between good and evil was developed and spread by the Persians. Before this, it seems to have been touched on in Babylon with the victory of the god Marduk over Tiamat - the victory of order over chaos, an idea which might possibly stem from an earlier period. Persian religious thought, governed by the idea of the polarity of good and evil, penetrated the entire ancient world of that time. Mostly artists drew upon local portrayals of gods and malevolent or guardian djinns. They dominated a people who went on seeing them as they had always been, and the Persian artist, using scenes that were already well known, elaborated them not only in the way they were depicted but also in the purpose for which they were intended. Their treatment is disturbingly cold and detached, and the protagonists seem totally unconcerned with whatever they are doing. On the other hand, if we look at these scenes from another point of view we shall see that the artist invariably produced set pieces that were extremely fine as architectural ornamentation, as, for example, the motif of the lion attacking a bull, which had possibly been chosen because it could symbolise one of the religious themes that was later to take root: Mithra the sun god slaying the bull. It was at this time that the idea of survival

after death, and the mediation of a spirit or a god that was the guide

of souls, took a firm hold. Royal tombs, far from being concealed as they

had been in Babylonia or in Egypt, stood proudly beneath the sky like

the mausoleum thought to be the tomb of Cyrus. The royal rock-tombs at

Naksh-i-Rustam and Persepolis were very well known, a fact which explains

why they were plundered. On the tomb at Naksh-i-Rustam the king, standing

on a dais, towers above a facade (carved out of the rock) in imitation

of his earthly home; he is alone before a fire altar under the |

|

|

The Splendour of Persian Art The artist had also to create for the world some impression of that vast state which was the Persian empire and of the tens of thousands of subjects living under its sway. This he tried to do in the bas-reliefs which adorned the palaces, exploiting to the full all the splendour and magnificence of the court and the surroundings in which the king lived. The Assyrian kings had surrounded themselves with scenes of atrocious barbarity, like the banqueting scene where Assurbanipal and his queen feast before the head of a defeated enemy that hangs from a hook, the bas-reliefs showing heaps of enemy heads cut off at the neck and meticulously counted by the scribes, the impaled bodies standing out against the landscape (a universal reminder of the fate awaiting rebels), battle scenes with their horrifying confusion of mangled bodies and appalling atrocities, and, lastly, the hunting scenes which acclaimed the courage of the king. The Persians portrayed nothing like this on their palace walls. The stairway balustrades, like the palace halls, were decorated with great ornamental friezes whose chosen theme was a feast where a crowd of courtiers press round the king to pay him homage while a line of tribute-bearers approaches. The artist was able to produce a series of the most vivid tableaux, fascinating in the variety of people and tributes depicted, that far and away surpassed King Shalmaneser's timid attempt on the Black Obelisk at Nimrud. The figures grasp each other by the hand; some turn to talk to the person behind, or hold the shoulder of the man in front, just as in some fabulous procession which at night by the flickering light of torches could leap into life on the walls. But finally we are overcome by a feeling of weariness and monotony when faced with these scenes which recur in everyone of the palaces and sometimes even several times over in the same palace. We must set aside, then, our own opinions if we are to understand this art that does not fit in with Western attitudes, for a Persian artist, if he had not penetrated to their deeper significance, could make just the same complaint of our cathedrals with their Nativities and Crucifixions. What the Persian artist wanted to produce was a great, uniformly decorated, frieze. We watch a procession in stone where almost all the figures are shown strictly in profile, standing out from the wall. Light and Colour The fantastic colours used by the artists for the bodies and wings of these djinns, possibly with some magical purpose, seem to have been inspired by a world of dreams where fancy rules supreme: such, for example are the glazed panels where we see two sphinxes turning their heads backwards towards the doorways (for they were set between the entrances so that no person coming in could pass unnoticed before their brown, inscrutable, mysterious faces. Similarly, the innumerable archers at the king's side had a magic significance, almost a security against any possible desertion on the part of the actual guard, who had, in fact, given the monarch such poor protection. At Susa, as at Persepolis, there are friezes wholly devoted to lines of guards, but in glazed bricks, vivid and glowing warmly in this light, with all the rich ochres and yellows and, as in Babylon, invariably standing out from a blue ground, the forerunner of the incomparable blues of the Ispahan mosques. The artist has paid 'attention to racial differences among the archers by distinguishing the swarthy complexioned southerners from the fair-skinned men of the north. The lavish magnificence of their embroidered silk robes appears to be exactly matched by the description of the immortals crossing the Dardanelles by a bridge of boats, crowned with flowers and with myrtle branches beneath their feet; and we can understand how these archers, though of unsurpassed skill as marksmen, should have been so hampered by their clothes when it came to a hand-to-hand tussle with the well-armed Greek infantry. It is not difficult to imagine the envy of the Greeks, a young and poor people then, as they gazed at the splendour and wealth of Asia. |

|

|

The Cosmopolitan Empire Persia then appeared to be the country that was potentially a centre for every kind of activity: in 512 Darius ordered Scylax of Caryonda, the Carian captain, to sail down the Indus. The Greek doctor Ctesias lived at the court of Darius II and Telephanes of Phocaea worked for the King of Kings for the greater part of his life. This in part explains the infiltration of Greek and other foreign influences, along with the use of foreign labour with which the foundation charter of the palace of Darius at Susa (translated by Father Scheil), is very much concerned; this charter is, in this respect, one of our most useful and instructive sources. There the king lists all the materials required, from. India to Greece, for the building of his palace: they came accompanied by craftsmen experienced in working with these materials. Cedarwood was brought from Lebanon; brick walls were built by Babylonians. There was continual contact between all the different regions of the empire and the neighbouring countries; ambassadors, scholars and artists travelled from one country to another and the fame and reputation of the East, with the Persians as its representatives, spread far and wide. So the Greeks came to be acquainted with the sciences of ancient Babylonia (handed down by initiation ceremonies) and it has been pointed out that Pythagoras' headgear was, in fact, that worn by the initiated. But these interchanges often produced clashes. Trade was made considerably easier by the adoption of the daric (which can be traced back in origin to Croesus) and was backed up by the great banks established in Babylonia by Murashu and his sons. The ancient great highway - the old Semiramis road - was extended to Susa, and at intervals along it monuments were set up in honour of the King of Kings, like the Behistun rock where it was a feat of daring for sculptors to climb up (and this was repeated in modern times by archaeologists) and to carve bas-reliefs to the glory of Darius and engrave his address from the throne in three languages (Babylonian, Elamite and Persian). The fact that the Achaemenids were compelled to make use of other languages besides Persian in order to communicate with all the subject peoples of the empire has enabled scholars to decipher cuneiform script - with the help, too, of a successful reading of an Egyptian cartouche on an oil-bottle where the name of Xerxes appears. When they came to power the renown of the

Persians spread throughout the ancient world; before this, Nabonidus had

been told by the god Marduk, who had appeared to him in a dream, of Astyages'

downfall and the coming of Cyrus. We have a typical example of the infiltration

of Medo-Persian influence in Babylon, where Nebuchadnezzar II had built

the hanging gardens, to delight his wife Amytis, the grand-daughter of

Astyages who remembered with longing the gardens or 'paradises' which

were part of every Achaemenid palace, those The Magnificence of the "King of Kings" Many new characteristic features came into

being under Persian rule. After the Sumerian patesis, the viceroys of

the gods, after the rulers of Babylon and Assur, kings of 'everything

that was', the Persian king appeared as something quite different; from

now on, royal protocol conferred upon him the title of King of Kings.

He was created by Ahura Mazda to govern that vast land, entrusted by him

with that great kingdom with its fine warriors and 'excellent horses',

in recognition of the fact that his forebears had Texts and monuments alike have nothing to say of the Persians' religion, which we can only begin to appreciate by its contribution to culture - so unlike anything that happened in Greece - as its light shone throughout the ancient world long after the collapse of the Achaemenid empire. Crystallised within the Persian civilisation was an Oriental civilisation many thousands of years old; but a new spirit had swept across the great plateau in the tracks of those audacious horsemen, and when Alexander embarked on his conquest of Asia he followed the routes taken before him by the King of Kings. See also: Greek Architecture (900-27 BCE). |

|

• For more about ancient civilizations, see: Homepage. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ANCIENT

ART |