Fine Art Painting

Genres, Mediums, History, Movements: Oils,

Watercolours, Acrylics.

MAIN A-Z INDEX

|

Fine Art Painting |

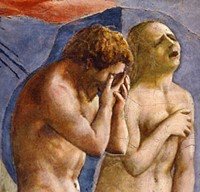

Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (detail), Brancacci Chapel, Florence (c.1426-7) by Masaccio. See Famous Paintings Analyzed. |

Fine Art Painting

|

|

|

Definition: Form of 2-D Visual Expression: The art of painting consists of the arrangement of shapes, lines, colours, tones and textures on a two-dimensional surface, thus creating an aesthetic image. More than that one cannot say, the sheer variety of possibilities precludes any more precise definition. The finished painting may be wholly representational and naturalistic - such as those of the photorealists (eg. Richard Estes) - or wholly abstract - comprising only geometric shapes (like those by Piet Mondrian, or Bridget Riley) - or anywhere in between. In genre terms, it might be a narrative history work, a portrait, a genre-scene, a landscape or a still life. It may be painted using encaustic, tempera or fresco paint, oils, acrylics or watercolours, or any of the new contemporary mediums. And as art critics and historians can testify, there are countless conflicting theories about the function, design, style-hierarchy and aesthetics of painting, so perhaps the safest thing is to say that as "visual artists", painters are engaged in the task of creating two-dimensional works of visual expression, in whatever manner appeals to them. |

|

WORLD'S GREATEST

ART |

|

ART OF PAINTING WORLD'S COSTLIEST

ART VISUAL ARTS CATEGORIES WORLDS TOP ARTISTS QUESTIONS ABOUT PAINTING GREATEST ARTISTS |

Painting Composition and Design Sometimes called "disegno" - a term derived from Renaissance art which translates as both design and drawing, thus including the artist's idea of what he wants to create as well as its execution - painting design concerns the formal organization of various elements into a coherent whole. These formal elements include: Line, Shape/Mass, Colour, Volume/ Space, Time/Movement. (1) Line encompasses everything from basic outlines and contours, to edges of tone and colour. Linework fixes the relationship between adjacent or remote elements and areas of the painting surface, and their relative activity or passivity. (2) Shape and Mass includes the various different areas of colour, tone and texture, together with any specific images therein. Many of the most famous paintings (eg. The Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci) are optically arranged around geometric shapes (or a mixture thereof). Negative space can also be used to emphasise certain features of the composition. (3) Not surprisingly, given that the human eye can identify up to 10 million differing hues, colour has many different uses. (See colorito.)It can be used in a purely descriptive manner - Egyptians used different colours to distinguish Gods or Pharaohs, and to differentiate men from women - or to convey moral messages or emotional moods, or enhance perspective (fainter colours for distant backgrounds). See also: Titian and Venetian Colour Painting 1500-76. Above all, colour is used to depict the effects of light (see the series of Haystacks or Rouen Cathedral by Claude Monet), while many great painters like Caravaggio and Rembrandt have exploited the contrast between colours for dramatic effect - notably in the technique of chiaroscuro (see Rembrandt's The Night Watch). See colour in painting. |

|

|

|

|

(4) The elements of Volume and Space are concerned with how the painter creates depth and spatial relationships within the flat surface of the picture. Traditional painters do this by deploying the concept of linear perspective, as developed during the Florentine Renaissance by Piero della Francesca and others (see also the illusionistic techniques of quadratura and foreshortening), while Cubists like Picasso, Braque, Duchamp and Juan Gris, expressed space and volume by showing a range of overlapping "snapshots" of the same object as if viewed simultaneously from different viewpoints. Still others, like naive (naif) or primitive-style painters show objects not in their true-life naturalistic relationship to each other, but separately, from whatever angle best shows their characteristic features - this includes the flattened stylistic forms used, for instance, by the Egyptians. (5) The elements of Time and Movement concern how the viewer's eye is allowed to experience the picture, in terms of speed and direction, both for its narrative development (eg. in large-scale history murals), its trompe l'oeil potential, or its angular opportunities for study (eg. Cubist paintings depicting several "snapshots" of the same objects). |

|

|

In addition to creating a visual object, an artist also aims to infuse it with a degree of intellectual content, in the form of symbolism, a moral or social message, or some other meaningful content. Thus, the famous American critic Clement Greenberg (1909-94) once stated that all great art should aim to create tension between visual appeal and interpretive possibility. The history of art is full of examples of interpretive content. For example, Egyptian art is noted for its iconographic imagery, as are Byzantine panel paintings and pre-Renaissance frescos. Renaissance pictures, such as those by Old Masters such as Botticelli, Leonardo and Raphael , often took the form of highly complex allegorical works, a tradition that was maintained throughout the succeeding Baroque and Neoclassical eras of the 17th and 18th centuries. Even still lifes, notably the genre of Vanitas painting, were infused with moralistic allegory. However, the tradition waned somewhat during the 19th century, under the dominant influences of Romanticism, Impressionism and to a lesser extent Expressionism, before reemerging in the 20th century, when Cubism and Surrealism exploited it to the full. For more, see: Analysis of Modern Paintings (1800-2000). Encaustic One of the main painting mediums of the ancient world, encaustic painting employs hot beeswax as a binding medium to hold coloured pigments and to enable their application to a surface - usually wood panels or walls. It was widely used in Egyptian, Greek, Roman and Byzantine art. Fresco Fresco (Italian for "fresh") refers to the method of painting in which pigments are mixed solely with water (no binding agent used) and then applied directly onto freshly laid plaster ground, usually on a plastered wall or ceiling. The plaster absorbs the liquid paint and as it dries, retaining the pigments in the wall. Extra effects were obtained by scratching techniques like sgraffito. The greatest examples of fresco painting are probably Michelangelo's "Genesis" and "Last Judgment" Sistine Chapel frescoes, and the paintings in the Raphael Rooms, such as "The School of Athens". Tempera Instead of beeswax, the painting medium tempera employs an emulsion of water and egg yolk (occasionally mixed with glue, honey or milk) to bind the pigments. Tempera painting was eventually superceded by oils, although as a method for painting on panels it endured for centuries. It was also widely used in medieval painting in the creation of illuminated manuscripts. For more details about this genre, see: Gothic Illuminated Manuscripts (1150-1350). |

|

Oils The dominant medium since 1500, oil painting uses oils like linseed, walnut, or poppyseed, as both a binder and drying agent. Its popularity stems from the increased richness and glow that oil gives to the colour pigments. It also facilitated subtle details, using techniques like sfumato, as well as bold paintwork obtained through thick layering (impasto). Important pioneers of oil paint techniques included (in Holland) the Flemish painters Hubert and Jan Van Eyck, and (in Italy) Antonello da Messina, Leonardo Da Vinci, and especially members of the school of Venetian painting, including Giovanni Bellini and Titian. Watercolours and Gouache Watercolour painting - a rather unforgiving medium - developed in England - uses water soluble pigments pre-formulated with a binder, typically gum arabic. When watercolours are thickened, made opaque and mixed with white, it is called gouache. Early pioneers of watercolour painting include Thomas Girtin and JMW Turner. Gouache was an important medium for many of the best miniaturists involved in early miniature portrait painting, before the use of enamel. Acrylics The most modern of all mediums, acrylic painting is a man-made paint containing a resin derived from acrylic acid that combines some of the properties of watercolour and oils. Highly versatile, it can be applied to almost any surface in varying amounts, ranging from thin washes to thick impastoed layers. It can give either a matt or gloss finish and is extremely fast-drying. Popular with many famous painters, including David Hockney, acrylic painting may yet supercede oils during the 21st century. Murals Dating back to Paleolithic cave painting, murals were painted in tombs, temples, sanctuaries and catacombs throughout the ancient Western world, including Etruria, Egypt, Crete, and Greece. Initially devoid of "depth", they were fully developed as a medium for Biblical art during early Renaissance, by fresco artists like Giotto (see: Scrovegni Chapel frescoes), and later by Masaccio, Fra Angelico, Raphael and Michelangelo. As interior decoration became increasingly dominated by stained glass and tapestry art, mural painting declined, although a number of site-specific works were commissioned during the 19th and 20th centuries. Panel Painting The earliest form of portable painting, panels were widely used (eg) in Egyptian and Greek art (although only a few have survived), and later by Byzantine artists from 400 CE onwards. As with murals, panel-paintings were rejuvenated during the late Gothic and early Renaissance period, chiefly as a type of decorative devotional art - eg. "The Ghent Altarpiece" (1432) by Hubert and Jan Van Eyck, and "The Deposition" (1440) by Roger van der Weyden. For details of Renaissance panel painting in 16th century Venice, a genre and period which illustrates the colorito approach of the city, please see: Venetian Altarpieces (1500-1600) and Venetian Portrait Painting (1400-1600). See also: Legacy of Venetian Painting on European art. Wooden panel painting was especially popular in Flemish painting and other Northern schools, due to the climate which was not favourable for fresco murals, and remained so up until the end of the 17th century. Easel Painting This form, like panel painting, was a form of studio art but used canvas as a support rather than wood panels. Canvas was both lighter and less expensive than panels, and required no special priming with gesso and other materials. From the Baroque era onwards (1600) oil on canvas became the preferred form of painting throughout Europe. It was particularly popular with new bourgeois patrons in 17th century Dutch painting (1600-80), notably in the form of portraiture, still life and genre works. |

|

|

Manuscript Illumination Dating back to celebrated examples from ancient Egypt, like the "Book of the Dead", this type of painting achieved its apogee during the Middle Ages (c.500-1000 CE) in the form of Irish and European illuminated manuscripts. Early examples of this type of book painting include: Cathach of St. Columba (early 7th century c.610-620), Book of Durrow (c.670), Lindisfarne Gospels (c.698-700), Echternach Gospels (c.700), Lichfield Gospels (730), Godescalc Evangelistary (781-83), The Golden Psalter (783-89), Lorsch Gospels (778-820), Book of Kells (c.800), Gospel of St Medard of Soissons (810), Utrecht Psalter (830), Ebo Gospels (835), Grandval Bible (840), Vivian Bible (845). Later examples of Medieval manuscript illumination include Romanesque works such as: the Egbert Psalter, St Albans Psalter, Winchester Bible, Codex Vigilano and the Moralia Manuscript; Gothic works such as: the Psalter of St Louis, Bible Moralisee, Amesbury Psalter, Minnesanger Manuscript, Queen Mary's Psalter; and International Gothic works like: Missal for the Chancellor Jan of Streda (1360, Prague, National Museum Library, MS); the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1416, Musee Conde Chantilly) by the Limbourg Brothers; the Annunciation by Jacquemart de Hesdin (1400, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris); the Brussels Hours (Brussels, The Belgian National Library, MS. 11060-1); the Hours of the Marechal de Boucicaut (Jacque-mart-Andre Museum, Paris); Le Livre du coeur d'Amours Espris (1465, Osterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna). Typically executed in egg-white tempera on vellum and card, these painted manuscripts featured extremely rich and complex graphic designs of Celtic-style interlace, knotwork, spirals and zoomorphs, as well as figurative portraits of Saints and Apostles. Sadly, the advent of the printing press in 15th century Germany put this art form out of business in Europe. Thereafter it survived only in the East, notably in the form of Islamic calligraphic painting and decorated texts, and miniatures from India. Scroll Painting Hand scrolls are a form of Asian art dating from c.350 CE, common to both Chinese painting and Japanese art. Composed of varying lengths of paper or silk, they featured a wide variety of ink and wash paintings whose subjects included landscapes, Buddhist themes, historical or mythological scenes, among others. For a guide to the aesthetic principles behind Oriental arts and crafts, see: Traditional Chinese Art: Characteristics. Screen/Fan Painting There are two basic types of painted screen: traditional Chinese and Japanese folding screens, painted in ink or gouache on paper or silk, dating from the 12th century - a form which later included lacquer screens; and the iconostasis screen, found in Byzantine, Greek and Russian Orthodox churches, which separates the sanctuary from the nave. This screen is traditionally decorated with religious icons and other imagery, using either encaustic or tempera paints. Painted fans - typically decorated with ink and coloured pigments on paper, card or silk, sometimes laid with gold or silver leaf - originated in China and Japan, although curiously many were actually painted in India. In Europe, fan painting was not practised until the 17th century, and only properly developed in France and Italy from about 1750 onwards. Modern Forms of Painting 20th Century painters have experimented with a huge range of supports and materials, including steel, concrete, polyester, neon lights, as well as an endless variety of "found" objects (objets trouves). The latter is exemplified in the works of Yves Klein (1928-62), who decorated women's nude bodies with blue paint and then imprinted them on canvas; and Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) whose work Bed (1955) consisted of the quilt from his own bed, painted with toothpaste, lipstick and fingernail polish. There are five traditional painting

genres. These are ranked as follows: History and Styles of Painting Origins The history of art has witnessed a wide range of painting styles. Beginning with pre-historic cave painting (eg. in the Altamira, Chauvet and Lascaux caves), it encompasses the murals and panel paintings of Egyptian, Minoan, Mycenean and Etruscan civilizations, as well as the classical antique style of Greek painting and Roman art. An excellent example from Classical Antiquity is the series of Fayum Mummy Portraits, found mostly in the Faiyum Basin near Cairo. The collapse of Rome (c.450 CE) led to the ascendancy of Byzantine art, based in Constantinople. Meanwhile Western Europe suffered four centuries of stagnation - The Dark Ages - before Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne the Holy Roman Emperor. Charlemagne's court sponsored a mini-cultural renaissance known as Carolingian art (750-900). This revival was maintained by Otto I, II, and III, the era of Ottonian art, before a revitalized Roman Church launched the successive cultural styles of Romanesque (1000-1200) and Gothic art (1150-1375). The main painting activities undertaken as part of these five movements, were icon panel paintings, religious fresco murals, and book illuminations. Proto-Renaissance Medieval Western painting was heavily regulated by convention. Not only was subject matter limited almost exclusively to the depiction of Biblical figures, but also there was a fixed canon of rules which laid down which Old and New Testament figures might be included, and how they should be recognized. The structure of the picture adhered to the "perspective of meaning", whereby important subjects were shown large, and less important ones on a smaller scale. Painters were also obliged to follow a formulaic set of conventions in their compositions, concerning (eg) colour, space and background. Thus naturalism was not generally permitted. The divine world of God, Jesus, The Virgin Mary, the Prophets, Saints and Apostles - which was the predominant theme - was viewed as a transcendental world, whose magnificence and glory were generally symbolized by a glowing gold ground. The first artists to challenge the rigidity of these painting rules were Cimabue and his pupil Giotto (1270-1337) whose fresco cycle in the Capella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel) in Padua introduced a new realism, using a far more naturalistic idiom. As a result Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) describes Giotto in his "Lives of the Painters" ("Vite de' piu eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani") (1550) as "the father of painting." Another innovator of the proto-Renaissance trecento period (c.1300-1400) was Ambrogio Lorenzetti (active 1319-48), of the Sienese School of painting. |

|

|

Early Renaissance While the old-fashioned styles of Byzantine art, and International Gothic were gradually playing themselves out in Siena (Italy) and in feudal royal courts across Europe, Giotto's creative ideas were being examined and developed in Florence during the Early Renaissance (1400-90). This movement saw four major developments: (1) a revival of Classical Greek/Roman art forms and styles; (2) Greater belief in the nobility of Man (Humanism); (3) Mastery of linear perspective (depth in a painting); and (4) Greater realism in figurative painting. Supreme painters of the Early Renaissance included: Tommaso Masaccio (c.1401-28) who painted a series of fresco paintings in the chapel of the Brancacci family, in Florence; and Piero della Francesca (1420-92) whose passionate interest in mathematics led him to pioneer linear perspective, with geometrically exact spaces and strictly proportioned spaces (see his The Flagellation of Christ, 1450s). Realism, linear perspective and new forms of composition were all further refined by quattrocento artists that followed, such as the Florentines Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1432-98) and Alessandro Botticelli (1445-1510), and the Northern Italian Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506). High/Late Renaissance High Renaissance painting (c.1490-1530), centred on Rome and driven by Pope Julius II (reigned 1503-13) and Pope Leo X (reigned 1513-21), witnessed the zenith of Italian Renaissance ideology and aesthetic idealism, as well as some of the greatest Renaissance paintings. All this is well exemplified in the work of Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519) (The Last Supper, Mona Lisa), Raphael (1483-1520) (The School of Athens) and Michelangelo (1475-1564) (the Genesis fresco in the Vatican Sistine Chapel). This High Renaissance trio were supported by other great painters from Venice, including Jacopo (c.1400-1470), Gentile Bellini (c.1429-1507) and Giovanni Bellini (c.1430-1516), Giorgione (c.1476-1510), Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) (c.1487-1576), Paolo Veronese (1528-88) and Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti) (1518-94). Northern Renaissance Meanwhile, in Northern Europe (Flanders, Holland, England and Germany), the Northern Renaissance evolved in a slightly different way, not least in its preference for oil painting (fresco being less suited to the damper climate), and its espousal of printmaking. Great artists of the era were: Jan Van Eyck (1390-1441), Roger van der Weyden (1400-1464), Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516), Albrecht Durer (1471-1528), and Hans Holbein (1497-1543). Mannerism Art in the turbulent cinquecento or 16th century, was characterized by a less harmonized, more forced style of painting, called Mannerism. Michelangelo's second Sistine fresco, The Last Judgment fresco is an exemplar, as is The Burial Of Count Orgaz by El Greco (c.1541-1614). Baroque During the late 16th century, in response to Martin Luther's Protestant Reformation movement (c.1520 onwards), the Roman Catholic Church launched its Counter-Reformation, using every means at its disposal to revive its reputation, including art. This coincided with the emergence of a new European style of painting known as Baroque painting, which flourished during the 17th century. In some ways, Baroque art was the apogee of Mannerism, being characterized by large scale extravagant theatricality in both form and subject matter. Rubens (1577-1640) was the Catholic Counter-Reformation Baroque painter par excellence. In Spain, another bastion of Catholicism, the leading painters were Diego Velazquez (1599-1660) and Francisco Zurbaran (1598-1664). In Italy, Caravaggio (1571-1610) became the leading Counter Reformation painter, famous for his naturalism and down-to-earth imagery. He was an important pioneer of Tenebrism and chiaroscuro, the painterly use of shadow popularized under the name of Caravaggism. A key centre of both Italian Baroque art and Caravaggesque painting was Naples - at the time the second biggest city in Europe, after Paris. For more information, please see: Painting in Naples (1600-1700). Dutch Realist School Non-Catholic Dutch Baroque art, and some Flemish Baroque art, was obliged to develop differently, since Protestant church authorities had little interest in commissioning religious works. However, growing prosperity among the merchant and professional classes led to the emergence of a new type of art-collector, whose pride in house and home triggered a new demand for easel art: in particular, genre-works, landscapes and still lifes. Thus arose the great Dutch Realist schools of genre painting in Delft, Utrecht, Haarlem and Leiden, among whose members we find geniuses like Rembrandt (1606-1669) and Jan Vermeer (1632-1675). Rococo By about 1700, the weighty Baroque idiom developed into a lighter, less serious style, which eventually took independent form in a movement known as Rococo. Exclusively French to begin with, this whimsical decorative style eventually spread throughout Europe during the 18th century. Its greatest exponents were the French painters Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), Jean-Honore Fragonard (1732-1806), Francois Boucher (1703-70) and the Venetian Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770): the latter renowned for his fantastic wall and ceiling fresco paintings. Rococo became closely associated with the decadent ancien regimes of Europe, notably that of the French King Louis XV and his mistress Madame de Pompadour. |

|

|

Neoclassicism and Romanticism (Flourished c.1789-1830) The French Revolution of 1789 coincided with the emergence of two differing artistic styles: Neoclassical art and Romanticism. Exponents of neoclassical painting looked to Classical Antiquity for inspiration; their pictures being characterized by heroicism, onerous duty and a tangible sense of gravitas. Its leading exponent was the French political artist Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). Other renowned Neoclassical artists included the German portraitist and historical painter Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-79), and the French master of the Academic art style, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). The movement's greatest contribution, however, was its architecture, which is still visible throughout the world. In contrast to the gravitas and universal values promoted by Neo-Classicism, Romantic painters sought to return to nature - exemplified by their espousal of spontaneous plein-air painting (eg. at the Barbizon, Pont-Aven, and Norwich schools of painting), and placed their trust in the senses and emotions rather than reason and intellect. Romantic artists tended to express an emotional personal response to life. Celebrated Romantics included John Constable (1776-1837), and JMW Turner (1775-1851) - important representatives of 19th century English Landscape Painting - Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) and Camille Corot (1796-1875); as well as the history painters and portraitists Francisco Goya (1746-1828) Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), James Barry (1741-1806), Theodore Gericault (1791-1824) and Eugene Delacroix (1798-63). See also English Figurative Painting (1700-1900). Later Romantic art included Levantine Orientalist painting, American frontier landscapes of the Hudson River School, the mystical works of the Symbolism Movement and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, as well as the fantasy dream-like pictures of the Magic Realism school. Realism Up until the 19th century, with the exception of 17th century Netherlandish art, painting focused primarily on "important" subjects, as defined by tradition the fine arts academies and the Paris Salon. Even when painters turned to less exalted subjects (eg. child beggars), typically they would depict them in an idealized manner. But in keeping with the new ideas of "Liberty, Fraternity and Equality", unleashed by the French Revolution, artists began to give equal priority to everyday subjects, which were depicted in true-life, naturalistic fashion. This new style - known as Realist painting - emerged mainly in France and attracted painters from all the genres - notably Gustave Courbet (1819-77), Jean-Francois Millet (1814-75), Honore Daumier (1808-79), Ilya Repin (1844-1930) and Thomas Eakins (1844-1916). The influence of 19th century French Realism continued into the 20th century, during which time it spawned numerous sub-movements such as Ashcan School (New York), Social Realism (assisted by Federal Arts Project) Precisionism (industrial scenes), Socialist Realism, Contemporary Realism, and others, and continues to this day.

Impressionist Painting By the latter half of the 19th century, Paris had become the undisputed centre of world art. It consolidated its position by giving birth to one of the greatest modern art movements of all time - Impressionism, whose principal adherents included: Claude Monet (1840-1926), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Edouard Manet (1832-83), Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), and Berthe Morisot (1841-95). Other painters associated with the Impressionist style, included Georges Seurat (1859-1891), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), James McNeil Whistler (1834-1903) and Walter Sickert (1860-1942). See also: Best Impressionist Paintings. Although the Impressionists dissolved as a 'group' during the early 1880s, the style spawned a number of related painting styles, loosely referred to under the headings Neo-Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. These included Pointillism, an offshoot of Divisionism, Intimism, and the American Luminism style of landscapes and seascapes, as well as artist-groups like the English Newlyn School and Camden Town Group, the decorative French painting styles of Synthetism (Gauguin) and Cloisonnism (Bernard, Anquetin) which inspired the Nabis, and the German Worpswede Group. Fin de Siecle and Early 20th Century Painting Between about 1882 and 1925, the art world witnessed a flurry of new painting styles. The two main movements of this outburst of modern art were: (1) Expressionism - a colourist style (coinciding with the short-lived Parisian Fauvist movement, led by Henri Matisse) featuring German Expressionism groups like Der Blaue Reiter, Die Brucke and Neue Sachlichkeit, and exemplified in the paintings of Wassily Kandinsky (1844-1944), Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Alexei von Jawlensky (1864-1941), Georges Rouault (1871-1958), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), Franz Marc (1880-1916) and Egon Schiele (1890-1918). See also: History of Expressionist Painting (c.1880-1930). (2) Cubism - a more intellectual style which featured Analytical then Synthetic Cubist painting, pioneered by Georges Braque (1882-1963) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). Cubist experimentation with the two-dimensional picture plane led to offshoot styles such as Futurism, the Italian artistic movement founded in 1909 by Filippo Marinetti (1876-1944); the Orphic Cubism (Simultanism) of Robert Delaunay (1885-1941); Rayonnism developed by the Russian artists Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) and Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962); the Russian Abstract art movement of 1913-15, known as Suprematism, led by Kasimir Malevich (1878-1935), and the Dutch De Stijl movement founded in 1917 by Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) and Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), which later became Neo-Plasticism. For more, see: Abstract Paintings. Early 20th century painting was also influenced by the decorative designs of both Art Nouveau (Jugendstil in Germany) and Art Deco.

Post-World War I Painting: Surrealism After the anti-art antics of Dada, the first international painting movement of the interwar years was Surrealism, whose irreverent, populist style became a major influence on later Pop-Art. After the pioneering metaphysical painting of Giorgio de Chirico, a major precursor for Surreal art, leading Surrealist artists included Max Ernst (1891-1976), Man Ray (1890–1976), Jean Arp (1887-1966), Joan Miro (1893-1983), Rene Magritte (1898-1967) and Salvador Dali (1904-89). Post-World War II: Abstract Expressionism (c.1945-65) By 1940, with Europe in chaos, the art centre of the world had shifted to New York, where a growing number of indigenous painters mingled with emigrant artists from France, Spain and Germany, finding patronage and support from the Guggenheim family, among others. The atmosphere was heavy with war, from which many artists recoiled, seeking comfort and meaning in abstraction rather than figurative art, which had effectively gone into decline following the demise of American Scene Painting and its mid-west variant Regionalism. Out of a combination of influential emigrant Europeans - such as Max Ernst (who married Peggy Guggenheim), the ex-Bauhaus painter Josef Albers (1888-1976), and the Armenian Arshile Gorky (1904-48) - plus unique American painters such as Mark Rothko (1903-70), Jackson Pollock (1912-56), and others - came Abstract Expressionism, with its variants of "action-painting" (Pollock and Lee Krasner), Colour Field Painting (Rothko, Still, Newman, Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland), Hard Edge Painting (Frank Stella) and Post-Painterly Abstraction (Ellsworth Kelly). In Europe, abstract expressionist painting evolved under the general banner of Art Informel (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze: Wols), whose sub-styles included Lyrical Abstraction (eg. Nicolas de Stael) Tachisme (Sam Francis), Matter Painting (Antoni Tapies), and Cobra group (eg. Asger Jorn, Karel Appel). A highly influential movement, Abstract Expressionism eventually led to Minimalism - one of the first contemporary art movements - via sub-styles like Op-art, championed by Bridget Riley (b.1931). Pop-Art (1960s) As the abstract style became ever more intellectual, other American painters sought alternatives rooted in - if not figuration then at least everyday reality. In the late 1950s, Jasper Johns (b.1930) and Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) began to explore the use of popular culture as a source of inspiration. This quickly led to the anti-intellectual Pop-Art movement, exemplified in works by Roy Lichtenstein (1923-97), Andy Warhol (1928-87) and David Hockney (b.1937), among many others. After declining during the early 1970s, it reappeared as Neo-Pop during the 1980s. Representational It's quite conceivable that all this is more apparent than real. For example, the lack of "international" movements might be creating an illusion that little progress is being made, despite significant local developments. Furthermore, postmodernist artists still have the ability to produce wonderful examples of abstraction - take for instance, the hallmark word art created by Christopher Wool (b.1955) in his black and white enamel paintings. So overall, to put it crudely, picture-making since the 1970s - despite much individual brilliance - does not seem to have produced its fair share of masterpieces. Instead, one might argue that postmodernist painters have had their hands full trying to find answers to these three questions: (1) How meaningful is figurative painting in an age dominated by photographic journalism and video film? (2) What more can abstract painting offer in the way of aesthetic originality? (3) To what extent can painting compete with more "modern" art forms like installation, for the attention of ordinary people, in art museums or other public venues? Perhaps traditional drawing and painting skills, which no longer receive the attention previously accorded them by art colleges and academies, are in decline, although not, it seems - at least to the same extent - in Russia, Eastern Europe and China, where perhaps modern video/photographic technology has less impact. On the other hand, new paint technology, as well as software graphics, has opened up painting to a wider range of practitioners, which can only be a positive development. |

|

• For more information about classical painting, see: Visual Arts Encyclopedia. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ART |