African Art

Characteristics, History of Traditional

Native Arts of Africa.

MAIN A-Z INDEX

|

African Art |

|

ANCIENT ARTS AND

CULTURES |

African ArtContents • Introduction For the chronology of early primitive art, see Prehistoric Art Timeline. |

|

PREHISTORIC ART |

The aim of this article is to place African tribal art in its social context rather than to discuss aesthetic appeal, stylistic zones, and the formal qualities of art objects. European art frequently uses symbols that are immediately meaningful to educated people - symbols of Christ, the saints, historical episodes. A knowledge of the meaning behind these symbols plays an important part in understanding and appreciating painting and sculpture. The same is true for African sculpture and other art forms: it is essential to discover whether a mask or a sculptured figure is made to entertain, frighten, promote fertility, or merely to be art for art's sake. We need to know whether a mask portrays a chief, a god, a slave, a were-animal, or a witch; whether a mask is worn on the head or over the face, carried, or secretly conserved in a cult-house. Although African art is presented here as an integral element of economic, social, and political institutions, in the final analysis the prime element is aesthetic. Despite the splendors of "classical" African art - like the sculptures of Nok, Ife, Benin - the main concern here is with the arts that continue to flourish in the chiefdoms, villages, and nomadic tents. (Note: For North African funerary art, and temple design, see: Egyptian Architecture.) |

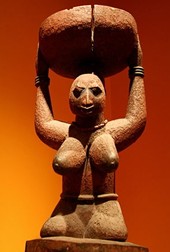

Yoruba Statuette of Female Figure (c.1900) Dedicated to Shango, the god of thunder. |

|

ANCIENT

CIVILIZATIONS EGYPT ART OF ISLAM DIFFERENT FORMS OF ARTS |

The earliest known prehistoric art of Africa - such as the Blombos Cave Engravings (c.70,000 BCE), the Diepkloof Eggshell Engravings (c.60,000 BCE), or the Apollo 11 Cave Stones (25,500-23,500 BCE) - was probably the work of yellow-skinned Bushmen, the aboriginal peoples of southern Africa. (For a guide to symbols used at Blombos, please see: Prehistoric Abstract Signs 40,000-10,000 BCE.) Bushmen are the oldest known natives of South Africa, although exactly when they appeared, and how far their history dates back, remains a mystery. It is not even certain if it was their ancestors who were responsible for the pictographs and petroglyphs which have been found at various prehistoric sites in the country. The Bushmen were driven back into the desert areas, not only by the white man, but also by the Hottentot invaders. The Hottentots are also a yellow-skinned race, so closely resembling the Bushmen that, according to some experts, it is inadvisable to separate them. There remains however, an enormous difference between their artistic achievements. None of any consequence can be attributed to the Hottentots, but the old Bushmen have to their credit some of the finest and oldest art in the world, at sites all over Southern Africa. The general character of Bushman rock art is naturalistic, and many of the images can be seen as pictographs, in that they express ideas and are not "art for art's sake." The large majority of the figures are men and animals, but there are a few other objects which are probably symbolic, although their meaning is not always clear; In some regions the pictures are painted in colour; elsewhere only engravings or chippings occur. The difference is due to the natural conditions of the country, although it is generally assumed that engravings are more archaic than paintings. The Prehistoric Colour Palette used by Bushmen artists in their cave painting consisted of earth pigments. Red and brown from bole or heematite; yellow from iron ochre; white from zinc oxide; black from charcoal or soot; blue from iron and silicic acid. The blue is particularly unusual and does not occur in the cave paintings of Europe. The fine lines found in Bushman paintings were drawn with thin hollow rods sharpened and used like quills.

African rock paintings and engravings were, curiously, discovered earlier than European ones: those in southern Africa as early as the mid 18th century, those in the North in 1847 when they were found by a group of French soldiers who reported engravings of elephants, lions, antelope, bovids, ostriches, gazelles, and human beings armed with bows and arrows. The best-known site of desert paintings in the north is the Tassili plateau, active from the age of Mesolithic art, which was explored and described by Henri Lhote in the 1950s. This is a mountainous area - 2000 sq miles (5180 sq km) of rock and shifting sand - now inhabited by only a few Tuareg shepherds. Thousands of years ago, when the paintings were made, the land was fruitful, covered with forests and crossed by rivers alive with fish. |

|

|

The style of the pictures is naturalistic, animated, and entirely different both from the conventionalised Libyan-Berber style, and from the early naturalistic, group of the Atlas. They seem to be much more closely related to South African Bushman art. Of particular interest are several polychrome paintings in the Tassili mountains representing graceful human figures with dappled cattle close by. To the south-west of this region, the French Ahagger expedition discovered in 1935 another site with the same kind of polychrome wall-paintings, showing various animals, but chiefly cattle. A few human figures are distinguished by extraordinarily animated and often graceful movements. The work is carried out entirely in spaces, so that they are genuine paintings and not linear drawings. On the same site, however, there are also a number of prehistoric engravings similar to the type in the Atlas region. There is a strong similarity between the Ahagger paintings and Bushman art, and, in addition they have a striking resemblance to the art of Ancient Egypt. Some of the Saharan paintings depict Negroes and a hunting way of life (dating from the prehistoric Roundhead period), while others (from the Cattle period, 4000 BCE - 800 CE) show pastoralists, figures with copper-coloured skin and straight hair who resemble the Fulani cattle-herders of the west African savanna. Art historians have suggested, and ethnographical research partly confirmed, that these works of Neolithic art were created by proto-Fulani groups: they contain elements that correspond to features of Fulani myths taught during boys' initiation rites, such as the hermaphroditic cow from whose chest emerge the heads of domestic animals, and the graphic portrayal of what resembles a Fulani initiation field (a circle with the sun in the center and heads of other cows, representing different phases of the moon, spaced around it). The rock pictures in the Atlas region of Algeria were first investigated in 1913. They are almost all engravings: only two pictures painted in ochre were discovered and these belong to earlier periods. Three principal art groups may be distinguished. There are first the very early naturalistic drawings of animals which are now either extinct in this area, or belong to a very remote geological period. The huge impressive design of a lion at Djattou is a good example. Next come a group of somewhat less naturalistic drawings, of slightly more recent date. Finally, there are the comparatively late Libyan-Berber designs, described as in part rather crude animal outlines, in part designs that are of a purely geometric and schematic character. |

|

|

Thanks mainly to archaeologists, African bronzes and terracottas no longer belong to an "unknown" past. Detailed comparative studies aided by radiocarbon dating have located them in historical contexts and continuing traditions. One of the best-known examples of an early sculptural tradition is that of "Nok", a label covering a range of terracotta sculpture of human and animal figures found widely distributed across northern Nigeria. They first came to light in tin mines near the village of Nok in Zaria province and have since been dated to the 4th or 5th century BCE. Some art historians have detected similarities between the stylized human figures and the naturalistic animals of Nok and the undated stone sculptures of Esie, the Nomoli figures of Sierra Leone, and the Afro-Portuguese ivories carved at Sherbro. But a more convincing suggestion is that the Nok style - the main features of which are a spherical or conical head, and eyes represented as segments of a sphere with the upper lid horizontal and the lower lid forming a segment of the circle - has many features in common with that of Ife, the religious and one-time capital of the Yoruba people. One thing is certain: the traditions of African art have not been without development. Radiocarbon dating and oral traditions suggest, for example, that the naturalistic style of sculpture at Ife lasted for about as long as bronze-casting in Benin. However, the rich Ife style shows an unvarying canon from the 10th to the 14th centuries, while in Benin, from the 15th to the 19th centuries, the progression from a moderate naturalism to a considerable degree of naturalization is very marked.

|

|

Less is known about the arts and civilizations of Sao (Lake Chad) and Zimbabwe, but enough to show that they are indigenous African cultures: there is no longer need to invoke Egyptian, Phoenician, or Portuguese influences. Archaeologists have shown, for example, that the walls and towers of Zimbabwe were raised by African builders and from African sources of inspiration. Nor is there any doubt about the Africanness of the Cross River akwanshi of southeastern Nigeria and neigh boring Cameroon - stone figures that resemble no other works of art in any medium in the whole of Africa. They are phallic in shape, with a general stylistic progression from phallus to human form. Some are little more than dressed and decorated boulders but they are distinguished by profuse surface decoration centred on the face, breasts, and navel. Other less well-known examples of "classical" African art are the bronze sculptures of Nupe and Ibo, in Nigeria. The bronzes of Ibo Ukwu were discovered in 1938 when a cistern was dug in the village. The site proved to be a repository for elaborately decorated objects - vessels, mace-heads, a belt, and other items of ceremonial wear. A grave excavated nearby contained a crown, a pectoral, a fan, a fly-whisk, and beaded metal armlets, together with more than 10,000 beads. Radiocarbon tests agree in dating these objects to the end of the 1st millennium, which makes this the earliest bronze-using culture of Nigeria. The bronzes are extremely detailed castings with elaborate surface decorations, but they differ from other African traditions of casting, such as those of Benin and Ife. Moreover, the high standard of wealth they reveal has no parallel in "democratic" Ibo-land where there are no centralized chiefdoms or wealthy aristocracies as among the Yoruba and Benin. Like Oceanic art, one of the most striking aspects of African art is that it is always very much an intimate part of social life, manifest in every aspect of Africans' work, play, and beliefs. The style and symbolism of paintings, figures, and masks, therefore, depend on their political, economic, social, and religious contexts, an examination of which often provides valuable insights into the meanings of African art. The Bushmen of the Kalahari desert, for example, hunt in an inhospitable environment, leading a life dominated by their absolute dependence on immediately available resources for survival. There is an intense relationship between the hunters and the hunted, between life and rain. The Bushmen's anxieties are expressed in their myths, their ceremonies, and their rites, and they are represented too in their paintings and engravings. Bushman rock paintings not only depict the animals they hunt, rain rituals, and the hunters themselves, but the animal species that have greatest mythical meaning. Another group, the Kalabari Ijo, are fishermen who also depend on chance - the luck of the tides, the shifting shoals of fish. Their art also directly reflects their way of life, their anxieties, and their myths. Living in isolated, self-contained communities in the mangrove swamps of southeastern Nigeria, they believe in water spirits, "Lords of the creeks" who live in a fabulous underwater world, who are, like the sculptures that represent them, anthropomorphic or zoomorphic, or a mixture of the two. The essence of the spirits is contained in the masks and sculpted headdresses worn by the fishermen at masquerades. The types of animals depicted in the masks are selected not for their economic importance but for their symbolic meanings and roles in Ijo myth and ritual. |

|

|

The numerous nomadic peoples of Africa are prevented by the very nature of their way of life from owning bulky or heavy works of art. In many cases they prefer literature, the most portable form of art - bucolic poems, epics, tales, and satirical pieces which vividly express a nomadic aesthetic. The Fulani of west Africa are a case in point. They have a positive disdain of the working of wood, iron, and leather; any cultural objects made from these materials which they possess are made by Negro groups on whose lands they graze their cattle. Even Fulani who have settled in villages prefer to give artistic expression to architecture, elaborate clothes, and ornaments. Authentic Fulani art is therefore rare, and restricted to details of dress, amulets, head-dresses, girls' anklets, ceremonial tools, and containers, and the body itself. Indeed, the Fulani have developed a veritable aesthetic of personal appearance, involving various forms of body art including body painting and face painting, as well as piercings and tattoos. From childhood they learn to decorate and paint themselves, fashion their hair into wonderful shapes and patterns, cultivate splendid styles of walking; mothers even massage the skulls of their babies to achieve ideal shapes. During annual ceremonies, which are both sadistic tests of manhood and male beauty contests, youths use all the arts of personal decoration - the body is oiled, painted, and ornamented. The men line up before the judges, "like sumptuous images of gods", their faces painted in red and indigo patterns, their hair decorated with cowries and surmounted by tall headdresses. On both sides of their faces hang fringes of ram's beards, chains, beads, and rings. Old women loudly berate those youths who do not come up to the highest standards of Fulani beauty. The greatest contribution Africa has made to world culture is its fine tradition of sculpture, although it was hardly known outside the "dark" continent until towards the end of the last century. Then, works that had previously been considered only as colonial trophies and weird museum objects attracted the attention of European artists keen for new experiences. Andre Derain (1880-1954), Maurice De Vlaminck (1876-1958), Picasso (1881-1973), and Matisse (1867-1954), were in turn overwhelmed by the expressive and abstract qualities of the figures and masks that turned up in Paris from the distant Congo and the French Sudan. Juan Gris even made a cardboard copy of a funerary figure from Gabon. The interest of these painters led to a generally heightened sensitivity to the qualities of African sculpture, although for many years it was a sensitivity that could only react to the pure form and mystery of the sculpture from ignorance of its function or symbolism. Today we are better informed, although whole corpora of African art remain mysterious entities since they were collected long ago, as curiosities, from people who had lost awareness of their uses or symbolic meanings. Among the Dogon of Mali there are a number of famous old sculptures, known as tellem, about which neither the Dogon nor archaeology can tell us anything (although innumerable art historians continue to make more or less inspired guesses). Tellem figures usually have uplifted arms and are mostly female or sometimes hermaphrodite. Others include animals or anthropomorphic figures carved along the lines of the original curved pieces of wood. With sculptures of this kind we are restricted to formal comparisons of style and subjective aesthetic appreciation. To this class belong the Fang masks and Kota figures, once the new-found "idols" of Derain and Epstein. The plaque behind the head of the Kota figure has been described, confidently, as "rays of the sun", "horns of a goat", "a crescent moon", and a "Christian cross". The majority of Africans are not kings, priests, witchdoctors, and sorcerers, but farmers who spend the greater parts of their lives producing grain or cultivating root crops. Their aesthetic life is closely linked to this fact of their existence. Some of the greatest sculptural traditions of Africa are represented by masks and figures produced to assure the fertility of the fields and the survival of their cultivators. The Bambara, a Mandinka group of more than one million people living in Mali, have become noted for their metalwork, basketry, leatherwork, weaving, dyeing, and woodcarving. Bambara masks are associated with four major cult associations: the n'domo, komo, kove, and tyi wara. These societies bring out their masks during both dry and wet seasons; they "help" with the sowing, weeding, and harvesting of the Bambara's staple crop, millet, and celebrate the coming and going of rain. The n'domo mask, with its vertical horns, symbolizes growing millet - the corn will stand up strong and erect like the horns of the mask. The horns are eight in number and rise up straight in a row, like stretched fingers above the top of the head and on the same plane as the ears. The horns represent, in a schematic way, the various episodes of the Bambara creation myth, the eight horns in the ideal mask representing the eight primordial seeds created by God for the building of the universe. The basic meaning of the horn symbolism derives from the assimilation of these organs to the growth of grain and the human liver - Bambara farmers say that animal horns are to animals what the liver is to humans and what vegetable shoots are to the earth. The symbolism and rites of other Bambara societies and masks are also closely related to the prosaic activity of farming. The komo mask represents the hyena, the great laborer of the soil and guardian of life. The tyi wara mask represents a fabulous being, half man, half animal, who in the past taught men how to farm. During the sowing and growing seasons the tyi wara antelope mask represents the spirits of the forest and water, and assures fertility to the fields and to man.

|

|

|

The Art of the African Kingdoms Art is universally a means of glorifying persons of rank. The presence of objects elaborately carved in such precious materials as gold, silver, or ivory usually indicates the presence of a ruling class, surplus wealth, and the wherewithal to employ specialized craftsmen. In Africa, most lost-wax bronze castings, for example, require a highly specialized production technique and although it is not an art entirely restricted to kingdoms, it receives its greatest elaboration where the chief or a wealthy caste can afford to maintain a group of specialized artists. In Benin the privilege of working bronze was reserved for a special corporation who lived in a special quarter of the town and who came under the control of the Oba - the ruler. Among the Bamileke, artists were thought of and treated as servants, even slaves, of their chiefs in whose palaces they lived and through whom they sold their work. In these situations African art is not the result of "instinct" - capturing the soul of an animal or object through a "primitive ecstatic imagination" - but the product of training, apprenticeship, and a close knowledge of tradition. The artist in an African chiefdom worked portraits, insignia, and emblems to portray the king and his royal relatives as special, awe-inspiring figures, and to make them outlast the short periods of their lifetimes by commemorating them in art. So kings are shown as powerful and beautiful, without blemish and usually without expression, bedecked with royal symbols. The chiefs themselves wear splendid cloths and ornaments, sit on high, ornate stools, and sleep on elaborately carved beds. Artistic production under royal control is also used to emphasize the need for the royal caste to control its subjects, and princes often use art objects to terrify citizens. In Africa, as well as in Europe, the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a chief or an oligarchy often results in a local renaissance of the arts. Ashanti and Dahomey are good modern examples, where brilliant courts, receptive to multiple influences, produced distinctive and sumptuous art styles. In Dahomey the king concentrated on the working of silver, brass, and the production of appliqué work in his court. Wall sculptures decorated the palace, depicting historical and allegorical scenes and battles. Among the Ashanti, trade in gold and slaves brought great wealth to the kings who made the working of gold a court monopoly. Their goldsmiths formed a respected and privileged caste and produced ceremonial objects and portraits, the most famous of which is the gold mask from the treasury of King Kofi Kakari (Wallace Collection, London). Small weights cast in brass were also produced in order to weigh gold dust. One of the richest artistic zones in Africa covers the basins of the Kwango, Kasai, Katanga, and north-western Angola. This is an intermediary zone between forest and savanna occupied by farmers whose ancestors were the subjects of powerful kingdoms - the Luba, Tshokwe, Lunda, and Kuba. In each the artists were closely tied to the court and the royal cults. Among the Luba, for example, statues of kings and queens, caryatid stools, headrests, scepters, maces, and arms were produced to reflect the might and glory of the rulers. Among the Kuba the dominant Bushong group inspired an aristocratic culture that imbued social life with a passion for beauty and decoration. Kuba art and decoration flourished in all aspects of daily life - in building, metalworking, basketry, and weaving. Artistic endeavor became a way of life for many: even rulers were often artists and sculptors. Art was used to glorify Bushong kings, statues of whom are masterpieces of Kuba sculpture and have been made since the 17th century. All show the king seated, his legs crossed, wear-ing emblems of sacred kingship. They are small, barely more than 20 in (50 cm) high. Their faces are expressionless, their eyelids half closed; the artists have achieved remarkable appearances of timeless repose and deep gravity. Like all good kings they are fat and adorned with bracelets, anklets, belts, and necklaces. While the statues have a similar general form, they are not identical and individual details have been given to their faces. Yet they are hardly lifelike portraits: rather, conventionalized representations of kings with distinguishing characteristics. The main aim of the sculptor was to suggest the essence of kingship, an essence that is transferred from one king to the next. Chiefs and wealthy individuals are not the only patrons of art. In Africa important objects may be commissioned by lineage groups and, in societies without chiefs, works of art are most frequently held in common by members of associations of important men which perform governing as well as religious functions. The qualifications for membership of such cult associations, age grades, or secret societies differ from society to society. Sometimes all adult males are included; sometimes membership is restricted to individuals with special abilities or to those who possess particular statues or other sacred paraphernalia. Perhaps the most famous "secret society" is that of the Poro, the membership of which is most densely concentrated among the Mande- and Kpe-speaking peoples of Liberia and southern Sierra Leone although it also spreads, usually under different names, into Guinea and the Ivory Coast. Closely connected with the men's Poro are the Sande or Bundu women's associations which take the form of lodges among the women of specific chiefdoms. Both male and female societies maintain cycles of ceremonies connected with the recruitment and initiation of members. The main actors in the ceremonies are the uninitiated youths, all the adult men of the Poro, the adult women of the Sande, and the sacred elders representing the ancestors. They are joined by the masked impersonators of the nature spirits who are allied with the founders of the country. Throughout the area of the Paro and Sande we find generally two types of mask: the sleek, naturalistic masks associated with the name Dan, and the violently contrasting, roughly finished "Great Masks". There are also subsidiary masks used to enforce law and order and to educate the youths during the para initiation rites. Dan masks are well-balanced and harmonious. Their beauty derives from their naturalistic but highly simplified form. There are also miniature copies of the large masks, 3 to 4 in (7.5 to 10 cm) long, which are worn by those initiated into the secret societies. The Great Mask of the Poro is a

fierce, abstract representation of the demon of the forest. Its stylized

face is supposed to represent a long-dead, almost mythical ancestor of

great wisdom - the culture hero who introduced the Poro to the land of

men. The Mask is the symbol and oracle of the priest, who, as judge and

clan leader, is allowed to keep the mask on behalf of the Poro. Using

it he can obtain the sanction of the ancestors to punish criminal and

civil offenders. When important disputes are to be settled, the priest

carries the Mask to the meeting of the elders and places it on the ground

under a The use of the Great Mask in such a manner usefully provides divine ratification: judgment is considered to come from the spirit world, via the Mask, not from human beings. The Mask takes responsibility, for example, for the death from poisoning of someone who has undergone the sasswood ordeal. At important council meetings the Mask attends to ensure the presence and approval of ancestors. During violent quarrels the priest puts on the Mask and stops the litigants with his word. Lesser Masks,are also used to act as messengers or policemen. The Great Mask itself is characterized by protuberant eyes, faced with perforated china or metal disks, red felt lips, and a long beard hung with palm nuts or beads. Its typical thick patina comes from black, dried blood from sacrifices and the reddish remains of chewed kola nuts spat into the mouth of the Mask by the priest. During the actual Poro initiation rites the Great Mask appears mysteriously four times, merely to utter a secret phrase at which all fall prostrate to the ground. Minor masks, known as ge, are used to discipline and educate the initiates. The masks act as officials controlling the women and children outside the village, or work as scavengers rounding up food by begging, borrowing, and stealing from citizens. In appearance Ge masks are hideous, combining animal and human features. They are said to be artistic attempts to represent the belief that spirit power has both animal and spiritual attributes - the combination of traits, plus distortion, suggesting that there are certain unexplained phenomena more potent than the forces possessed by animals and humans separately. During the long initiation rites the women are led to believe that their children are swallowed by the masks, and scarification is said to be caused by the masks when they ingest the boys and later give birth to them. After their rebirth from the stomachs of the masks, the initiates sit on mats with blankets over their faces and in two days the masks teach them everything all over again - how to walk, eat, and defecate. Near the end of the session the Great Mask, with its deep growling voice, takes the boys to the waterside where they are washed and given new names. Girls are also initiated into the Bundu or Sande societies. At their coming-our ceremony they are anointed with oil, their hair is beautifully coiffed, and they wear rich clothes and jewelry. They parade to the accompaniment of songs, dances, and acrobatic performances, all performed by the masks. The Sande mask is shining black and the women bearers are hidden behind a cloth costume and raffia veils. The form and symbolism of the mask vary little. The most conspicuous fea-tures are the spiral neck, the complicated decoration of the hairstyle, and the small triangular face.

|

|

|

The most important feature of many African societies, and the source of political action within them, is kinship, in the form of corporate lineage organizations. Art frequently serves as an adjunct and symbol of the powers of lineage and clan. Among the Bakwele, lineage elders meet together in times of crisis and attempt to circumvent the trouble through the use of masks. Among the Fang and the Tiv tribes, where political power is transmitted through lineages, masks and statues are symbols of the rights of lineage heads to succeed and are used in the administration of social affairs. Similarly, among the Lega of eastern Zaire where chiefship does not exist and the lineage system functions without political leaders there are men of prestige who gain influence through their age, their personal magic, and their possession of art objects. The Lega have included carvers able to produce original and skillfully-made work in a variety of materials; their masks and figurines are used by the bwame association in its dramatic and ritual performances. The objects used in initiation ceremonies present a complex of symbols that help translate the essence of Lega society and thinking from bwame elders to initiates. They are corporately owned by lineages and as they pass from hand to hand they act as symbols of the continuity of Lega lineages and as the link between the dead and living members of the patrilineal family. In Ghana matrilineal lineages play an important part in maintaining the well-being of the Akan community, even when this community, as in the case of the Ashanti, is a centralized kingdom. Everybody traces his descent through his mother and belongs to his mother's lineage which consists of all the descendants of a common ancestress. The shrine of the lineage is in the form of a stool to which the head of the lineage offers food for the ancestors. In the main rite in the installation of an Ashanti chief, the new chief is lowered and raised three times over the sacred stool of the founder of his lineage. So the Ashanti stool is a symbol of the ancestors and of the lineage. It consists of a rectangular pedestal with a curved seat supported by carved stanchions. In the Kumasi stoolhouse there are ten black stools preserved in memory of ten Ashanti kings. The Golden Stool, traditionally believed to have been brought from the sky by the first king's priest and councillor, is a mass of solid gold with bells of copper, brass, and gold attached to it. Although our increased knowledge of African societies means that social and aesthetic functions are now assigned to many works of art previously considered as items for religious use only, much African art essentially has a religious and symbolic role. Members of the Yoruba, for example, are the most prolific African carvers and the largest concentration of their sculpture is religious art devoted to the cults of the various orishas or gods. Elsewhere, masquerades and other ritual performances use masks and carved figures to enact basic myths. Dogon art is explicitly religious in character: it depicts the ancestors, the first mythical beings, the atavistic blacksmith, the horseman with the ark carrying skills and crafts, and mythical animals. Their cosmological system and its relation to the content of their art has been explored in marvelous detail by a team of French anthropologists and art historians. So in order to comprehend the meaning of the Dogon Grand Mask we have to understand the meaning of the Dogon creation myth and the periodical Sigi festival, which regulate Dogon religious life. The Grand Mask is the double of the mythical ancestor; in making the new mask the carver deceives the soul of the ancestor and persuades it to enter into its new abode. When the Grand Mask is exposed to public view only the base pole is visible, since the head is buried in a pile of stones. Other Dogon masks are less sacred although their performances may reflect special signs and symbols and parts of the creation myth. Much of the cosmological thought of many African societies centers on twinness and androgyny. Among the Bangwa, a Bamileke people of Cameroon, twins and their parents are revered, twin births being considered perfect births representing a primordial and androgynous world when dual births were the rule. A woman who produces twins is feted by the whole village and elaborate sculptures are carved in the twins' honor. Both parents are given special attention and they are initiated into a religious association which plays an important role at fertility ceremonies and funerals. Bangwa sculpture has drawn inspiration from these twin parents and there are a number of statues of women and men carrying twins or wearing the symbols of twinship. Perhaps the best known of all Bangwa sculptures is a dancing figure, wearing a cowrie necklace and carrying a rattle and bamboo trumpet of the kind worn by mother-of-twin priestesses when calling the gods. Among the Yoruba, twins are also given special attention and there is a tradition of making images of them if one or both of them should die. These Ibeji figurines are nourished and cared for like real children, since each is believed to contain the soul of a dead twin. Everything done for a live child is done for the ibeji: it receives gifts and new clothes. Regular sacrifices are also made to it in an attempt to prevent the soul of the deceased from harming his living twin or mother. The carrying of the ibeji also prevents the mother from becoming infertile. Ibeji figurines are homogeneous in form - small, standing statuettes, nude in most cases although some are carved with an apron-like garment. Usually the proportional size of the head to the body is larger than that of the model; the genitals are carved, and the finished object colored - the head often stained a different colour from the body. The face is oval with prominent eyeballs, the forehead convex, the nose broad, the ears stylized. The lips are generally prominent, carved to form a kind of shelf because mothers feed them like their other babies. The arms are heavy and long, the hands stylized and joined to the thighs. Ibeji have a variety of scarification marks and hairstyles. Throughout Africa, witchcraft has some remarkably common features, the term itself usually referring to malign activities attributed to human beings who activate supernatural powers in order to harm others. Most witches work by night; they have the ability to fly and cover long distances in a flash. During peregrinations the body of the witch remains behind, the other self traveling invisibly or in animal form. They are fond of human flesh, making their victims ill and consuming their bodies after burial. So illness and death can be imputed to supernatural causes, and art objects, in association with magical techniques and ritual, are used to combat them. These objects are usually known as fetishes, a word that should really be reserved for a kind of "machine" - the word "fetish" comes from "fetico", the Portuguese word which means 'an object made by the hand of man fabricated by diviners or sorcerers and composed of various materials and medicines in order to draw upon the immanent life-forces of these substances'. In fact the additive material may be more important than the basic sculpture and consists of miscellaneous objects-crabs, animal bones and horns, teeth, feathers, parts of birds, buttons, cloth, and pieces of iron. Even if at first sight this conglomerate of objects seems haphazard and mundane, the accoutrements of a fetish all have symbolic value and meaning for their owners and the persons affected by them. The best-known fetishes were originally found in the Zaire region: some very early pieces are extant. In 1514 the Christian king of the Congo, Alfonso, is reported to have lamented the idolatry then prevailing among his subjects, declaring, "Our Lord gave, in the stone and wood you worship, for to build houses and kindle fire". Hundreds of types of fetishes have since been collected among the Bakongo and neighbouring peoples; they are known as Nkisi and all have the same general property of magical figures: they are able to inflict serious illnesses upon persons believed to be the cause of supernatural harm to others. In spite of its fame, this art form has not been studied in great detail. Throughout Africa, art objects are used in the divination of the supernatural causes of illness. Among the Bamileke, the traditional anti-witchcraft society, the kungang, is called together during times of crisis and epidemic to purify the country and decimate witches through the agency of their powerful fetishes. Kungang figures are carved with great skill; they usually have exaggeratedly swollen stomachs to indicate the dreadful dropsy which is one of the supernatural sanctions of the fetish. They also symbolize a more sympathetic magic: the bent arms represent the attitude of a begging orphan or a friendless person; the crouching position is the stance of a lowly slave. The kungang figures are believed to be imbued with powers accumulated over generations: these powers are concentrated in a thick patina formed from the blood of chickens sacrificed during anti-witchcraft oathing rites. Most of them have a small panel in their stomach or back which can be opened for the insertion of medicines. African art is multi-functional: it serves as a handmaiden of government, religion, and even economics. It also serves to entertain. West African masquerades, in particular, belie the generalization that in traditional African cultures there is no such thing as art for art's sake. Even when performances are associated with ritual and belief, aesthetics and theatricality are never ignored. In many West African societies, masquerades appear during the second burial ceremonies performed for all dead adults. In most cases the aim of the performance is not only to imbue religious awe or to seek ancestral protection, although these play a part, but to entertain the mourners and bring glory to the memory of the dead man and his successor. In all these dances it is the mask that matters, and for this reason the personality of the dancers is entirely subordinate to that of the mask. For the member of the masquerades the masks should be as spectacular as possible, and nothing - not even a monkey's skull or a European doll - is unacceptable on a mask which usually becomes much more elaborate once it has left the hands of its sculptor. Dyed plumes are added to the top and striated horns to each corner. Cockades are made from the fine hair of a ram's beard, and raffia is plaited and added to the chin in the form of a bear or attached to the front and back of the head of the masks. Skin-covering may be used, as among the Bangwa and Ekoi, to achieve textural rather than symbolic effects. Other Bangwa masks are beaded, while most of them are colored brightly with vegetable dyes or modern polychrome paints. A consideration of the decoration of the Ibo mbari houses will demonstrate that an art form cannot simply be categorized as "primarily religious" or even "primarily aesthetic". Here, elaborate stucco embellishments are created in honor of the goddess Ala at the beginning of the yam farming cycle. During a period of seclusion, specially selected persons create a profusion of sculptures and reliefs which are then displayed to the general public. During this period they sing songs in honour of the earth goddess and subsidiary gods. The mbari objects are diverse and may represent gods, human beings, hunting scenes, women and men copulating, and women giving birth. The main figure is Ala who is sculpted and painted last, sometimes with her two children. Associated with her are phallic figures, constructed for the invocation of human and farm fertility. Mbari is not only religious art but also a source of pleasure. Many of the figures are comic; some are obscene. Unnatural practices are illustrated with glee; women brazenly display their private parts. Gross indecencies are explained on the ground that a mbari should reveal every phase of human existence because it is a concentration of the whole of human life, including its taboos. Ibo art, like all African art, is marvellously eclectic. In the mbari, Christ on his cross stands alongside Ala the earth goddess. Tradition is renewed by the artist's individual inspiration and the use of external influences. Profound moral purpose and pure entertainment combine to make mbari a dynamic and immediate art form. Source: We gratefully acknowledge the use of material in the above article from "A History of Art" (1983), edited by Sir Lawrence Gowling. |

|

|

|

• For the main index, see: Homepage. Best

Art Museums |