Disegno

Definition, History of Florentine Method

of Drawing/Design.

![]()

|

Disegno |

|

DIFFERENT

FORMS OF ARTS |

Disegno: Italian Fine Art DrawingIntellectual Component of the Visual Arts The Italian word for fine art drawing is 'disegno'. But its meaning extends beyond the literal idea of draftsmanship. Disegno is the principle/method which underlies sculpture, as well as fine art painting and architecture. Above all, disegno constitutes the intellectual component of the visual arts, which justifies their elevation from craft to fine art, on a par with literature and music. The concept of disegno as the foundation of the visual arts can be traced back to the trecento period of 1354-60. In these years the Florentine humanist Petrarch wrote his dialogue 'Remedies Against Fortune' in which he states that graphis (latin for disegno or drawing) is the one common source of sculpture and painting. The idea is elaborated by many later Renaissance writers on art of whom probably the most important are Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455), Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), Federico Zuccaro (1542-1609). |

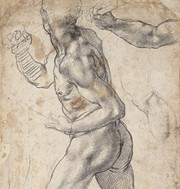

Male Nude Study (c.1504) by the Italian High Renaissance Artist Michelangelo Buonarroti. See Male Nudes in Art History. |

| Other

Graphic Art Forms - Charcoal drawing - Chalks - Conte Crayon - Pen and Ink drawings - Pastels - Pencil drawings |

'Disegno' Opposed to 'Colorito' In the particular context of 16th century and 17th century painting, disegno (identified initially with quattrocento Florentine art - whose exponents included Botticelli (1444-1510), Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519) and Michelangelo (1475-1564) - and later, with the influential Rome based French classical painter Nicolas Poussin and his followers), was opposed to Colorito (associated first with Venetian painting in the work of Giorgio Da'Castelfranco Giorgione (1476-1510) and Titian (1480-1576) and later with the Flemish painter Rubens (1577-1640) and his followers). (See also: Titian and Venetian Colour Painting c.1500-76.) For drawings and sketches by Titian, Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese, see: Venetian Drawing (c.1500-1600). For a genre and period which exemplifies the difference in approach between disegno and colorito, see: Venetian altarpieces (c.1500-1600). See also: Legacy of Venetian Painting on European art. |

|

Disegno is the Key Intellectual Element in Art Central to disegno was the use of drawings as the basic building blocks of a finished composition. By contrast, Colorito employed the direct application of colour (paint), to the canvas or panel. The distinction has a critical philosophical dimension. An artist wedded to disegno (the archetypal example would be Michelangelo) after long training in sketching from life and from other artistic sources such as ancient sculpture, devises complex figure poses which he works into a composition. He does this, not through direct observation of a model but through invention - the exercise of his imagination. Disegno combines both the ability to draw, which facilitates invention, and the capacity for designing the whole. But it is the latter - the imaginative and intellectual core of this process - which gives disegno its characteristic gravitas and which underpins academic painting theories as well as the academic hierarchy of the genres. In the latter, History painting - the genre most associated with disegno - is the highest form of painting. (For other relevant artforms see also: Graphic Art and Illustration: Book & Magazine.) Colorito is merely a Painting Technique In comparison with the intellectual thought which is so central to disegno, colorito simply involves encoding in paint the tonal and colour relationships of objects seen under particular light conditions. And the composition of a picture cannot precede it's "adornment" with colour (as in disegno-led painting), instead, it grows from the adjustments made by the artist on the canvas or panel. In theory, therefore, the colorito artist remains dependent on the model (what he sees) throughout the process of creating his painting, constantly checking the painted image with that of the model. In practice, colorito specialists too rely on their memory of visual effects: this probably explains the anatomical inaccuracies of many figures painted by Titian and the relative simplicity of his compositions. In general, the effects of colorito, such as the depiction of light, of reflections, of textures, of mood - these effects are produced to the detriment of those issues of structure which are the province of disegno. On a platonic scale of values, colorito depicts transient accidental aspects of things: the momentary effects of light, shade, colour, lustre, with their immediate appeal to the senses. Disegno on the other hand reveals the permanent invariable qualities of matter: volume, form and hidden order. The latter are, in this view, of greater appeal to the intellect and thus 'higher'. Disegno Made Simple To put it simply, disegno emphasises the idea of the artist as a God-like creator. Using his inventive genius, the artist conceives of a great composition, which (using his painterly skills) he proceeds to execute in accordance with his conception. Colorito on the other hand is merely a colouring skill, which a painter uses to replicate what he sees. Even if working in a studio from memory, colorito-driven artists are driven by the visual demands of the composition, which can end up being quite different from what he may have originally intended to paint. So while disegno entails fidelity to an original concept, colorito merely means executing a beautiful picture. In the eyes of cinquecento Renaissance aesthetics, there was a huge gulf between the two approaches: disegno was seen as true art, while colorito was considered more of a craft. |

|

• For facts about painting movements,

styles and Old Masters, see: History of

Art. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ART |