Italian Renaissance Art

Florence (Quattrocento), Rome and

Venice (Cinquecento).

A-Z of

ART MOVEMENTS

|

Italian Renaissance Art |

|

|

Renaissance Art in Italy (c.1400-1600)

|

|

ART HISTORIANS |

What Were the Characteristics of the Renaissance? In very simple terms, the Italian Renaissance re-established Western art according to the principles of classical Greek art, especially Greek sculpture and painting, which provided much of the basis for the Grand Tour, and which remained unchallenged until Pablo Picasso and Cubism. From the early 14th century, in their search for a new set of artistic values and a response to the courtly International Gothic style, Italian artists and thinkers became inspired by the ideas and forms of ancient Greece and Rome. This was perfectly in tune with their desire to create a universal, even noble, form of art which could express the new and more confident mood of the times. Renaissance Philosophy of Humanism Above all, Renaissance art was driven by the new notion of "Humanism," a philosophy which had been the foundation for many of the achievements (eg. democracy) of pagan ancient Greece. Humanism downplayed religious and secular dogma and instead attached the greatest importance to the dignity and worth of the individual. |

|

|

|

RELIGIOUS ARTS |

Effect of Humanism on Art In the visual arts, humanism stood for (1) The emergence of the individual figure, in place of stereotyped, or symbolic figures. (2) Greater realism and consequent attention to detail, as reflected in the development of linear perspective and the increasing realism of human faces and bodies; this new approach helps to explain why classical sculpture was so revered, and why Byzantine art fell out of fashion. (3) An emphasis on and promotion of virtuous action: an approach echoed by the leading art theorist of the Renaissance Leon Battista Alberti (1404-72) when he declared, "happiness cannot be gained without good works and just and righteous deeds". The promotion of virtuous action reflected the growing idea that man, not fate or God, controlled human destiny, and was a key reason why history painting (that is, pictures with uplifting 'messages') became regarded as the highest form of painting. Of course, the exploration of virtue in the visual arts also involved an examination of vice and human evil. |

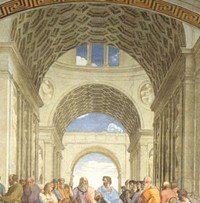

School of Athens (1509-11) by Raphael, in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Raphael Rooms at the Vatican. |

|

PAINT-PIGMENTS,

COLOURS, HUES |

What caused this rebirth of the visual arts is still unclear. Although Europe had emerged from the Dark Ages under Charlemagne (c.800), and had seen the resurgence of the Christian Church with its 12th/13th-century Gothic style building program, the 14th century in Europe witnessed several catastrophic harvests, the Black Death (1346), and a continuing war between England and France. Hardly ideal conditions for an outburst of creativity, let alone a sustained rinascita of paintings, drawings, sculptures and new buildings. Moreover, the Church - the biggest patron of the arts - was racked with disagreements about spiritual and secular issues. Increased Prosperity However, more positive currents were also evident. In Italy, Venice and Genoa had grown rich on trade with the Orient, while Florence was a centre of wool, silk and jewellery art, and was home to the fabulous wealth of the cultured and art-conscious Medici family. Prosperity was also coming to Northern Europe, as evidenced by the establishment in Germany of the Hanseatic League of cities. This increasing wealth provided the financial support for a growing number of commissions of large public and private art projects, while the trade routes upon which it was based greatly assisted the spread of ideas and thus contributed to the growth of the movement across the Continent. Allied to this spread of ideas, which incidentally speeded up significantly with the invention of printing, there was an undoubted sense of impatience at the slow progress of change. After a thousand years of cultural and intellectual starvation, Europe (and especially Italy) was anxious for a re-birth. Weakness of the Church Paradoxically, the weak position of the Church gave added momentum to the Renaissance. First, it allowed the spread of Humanism - which in bygone eras would have been strongly resisted; second, it prompted later Popes like Pope Julius II (1503-13) to spend extravagantly on architecture, sculpture and painting in Rome and in the Vatican (eg. see Vatican Museums, notably the Sistine Chapel frescoes) - in order to recapture their lost influence. Their response to the Reformation (c.1520) - known as the Counter Reformation, a particularly doctrinal type of Christian art - continued this process to the end of the sixteenth century. An Age of Exploration The Renaissance era in art history parallels the onset of the great Western age of discovery, during which appeared a general desire to explore all aspects of nature and the world. European naval explorers discovered new sea routes, new continents and established new colonies. In the same way, European architects, sculptors and painters demonstrated their own desire for new methods and knowledge. According to the Italian painter, architect, and Renaissance commentator Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), it was not merely the growing respect for the art of classical antiquity that drove the Renaissance, but also a growing desire to study and imitate nature. |

|

|

Why Did the Renaissance Start in Italy? In addition to its status as the richest

trading nation with both Europe and the Orient, Italy was blessed with

a huge repository of classical ruins and artifacts. Examples of Roman

architecture were found in almost every town and city, and Roman sculpture,

including copies of lost sculptures from ancient Greece, had been familiar

for centuries. In addition, the decline of Constantinople - the capital

of the Byzantine Empire - caused many Greek scholars to emigrate to Italy,

bringing with them important texts and knowledge of classical Greek civilization.

All these factors help explain why the Renaissance started in Italy. For

more, see Florentine

Renaissance (1400-90). If the framework for the Renaissance was laid by economic, social and political factors, it was the talent of Italian artists that drove it forward. The most important painters, sculptors, architects and designers of the Italian Renaissance during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries include, in chronological order: Cimabue

(c.1240-1302) General List of Renaissance Painters

& Sculptors NORTHERN EUROPE SCULPTORS |

|

|

Effects of the Renaissance on Painting and Sculpture As referred to above, the Italian Renaissance was noted for four things. (1) A reverent revival of Classical Greek/Roman art forms and styles; (2) A faith in the nobility of Man (Humanism); (3) The mastery of illusionistic painting techniques, maximizing 'depth' in a picture, including: linear perspective, foreshortening and, later, quadratura; and (4) The naturalistic realism of its faces and figures, enhanced by oil painting techniques like sfumato.

In Northern Europe, the Renaissance was characterized by advances in the representation of light though space and its reflection from different surfaces; and (most visibly) in the achievement of supreme realism in easel-portraiture and still life. This was due in part to the fact that most Northern Renaissance artists began using oil paint in the early 15th century, in preference to tempera or fresco which (due to climatic and other reasons) were still the preferred painting methods in Italy. Oil painting allowed richer colour and, due to its longer drying time, could be reworked for many weeks, permitting the achievement of finer detail and greater realism. Oils quickly spread to Italy: first to Venice, whose damp climate was less suited to tempera, then Florence and Rome. (See also: Art Movements, Periods, Schools, for a brief guide to other styles.) Among other things, this meant that while Christianity remained the dominant theme or subject for most visual art of the period, Evangelists, Apostles and members of the Holy Family were depicted as real people, in real-life postures and poses, expressing real emotions. At the same time, there was greater use of stories from classical mythology - showing, for example, icons like Venus the Goddess of Love - to illustrate the message of Humanism. For more about this, see: Famous Paintings Analyzed. As far as plastic art was concerned, Italian Renaissance Sculpture reflected the primacy of the human figure, notably the male nude. Both Donatello and Michelangelo relied heavily on the human body, but used it neither as a vehicle for restless Gothic energy nor for static Classic nobility, but for deeper spiritual meaning. Two of the greatest Renaissance sculptures were: David by Donatello (1440-43, Bargello, Florence) and David by Michelangelo (1501-4, Academy of Arts Gallery, Florence). Note: For artists and styles inspired by the arts of classical antiquity, see: Classicism in Art (800 onwards). Raised Status of Painters and Sculptors Up until the Renaissance, painters and sculptors had been considered merely as skilled workers, not unlike talented interior decorators. However, in keeping with its aim of producing thoughtful, classical art, the Italian Renaissance raised the professions of painting and sculpture to a new level. In the process, prime importance was placed on 'disegno' - an Italian word whose literal meaning is 'drawing' but whose sense incorporates the 'whole design' of a work of art - rather than 'colorito', the technique of applying coloured paints/pigments. Disegno constituted the intellectual component of painting and sculpture, which now became the profession of thinking-artists not decorators. See also: Best Renaissance Drawings. Influence on Western Art The ideas and achievements of both Early and High Renaissance artists had a huge impact on the painters and sculptors who followed during the cinquecento and later, beginning with the Fontainebleau School (c.1528-1610) in France. Renaissance art theory was officially taken up and promulgated (alas too rigidly) by all the official academies of art across Europe, including, notably, the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, the Accademia del Disegno in Florence, the French Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the Royal Academy in London. This theoretical approach, known as 'academic art' regulared numerous aspects of fine art. For example, in 1669, Andre Felibien, Secretary to the French Academy, annunciated a hierarchy of painting genres, modelled on Renaissance philosophy, as follows: (1) History Painting; (2) Portrait art; (3) Genre Painting; (4) Landscape; (5) Still Life. In short, the main contribution of the Italian Renaissance to the history of art, lay in its promotion of classical Greek values. As a result, Western painting and sculpture developed largely along classical lines. And although modern artists, from Picasso onwards, have explored new media and art-forms, the main model for Western art remains Greek Antiquity as interpreted by the Renaissance. It is customary to classify Italian Renaissance Art into a number of different but overlapping periods: • The Proto-Renaissance

Period (1300-1400) This chronology largely follows the account given in the authoritative book "Vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani" by the Renaissance commentator Giorgio Vasari (1511-74). |

|

The Renaissance, or Rinascimento, was largely fostered by the post-feudal growth of the independent city, like that found in Italy and the southern Netherlands. Grown wealthy through commerce and industry, these cities typically had a democratic organization of guilds, though political democracy was kept at bay usually by some rich and powerful individual or family. Good examples include 15th century Florence - the focus of Italian Renaissance art - and Bruges - one of the centres of Flemish painting. They were twin pillars of European trade and finance. Art and as a result decorative craft flourished: in the Flemish city under the patronage of the Dukes of Burgundy, the wealthy merchant class and the Church; in Florence under that of the wealthy Medici family. In this congenial atmosphere, painters took an increasing interest in the representation of the visible world instead of being confined to that exclusive concern with the spirituality of religion that could only be given visual form in symbols and rigid conventions. The change, sanctioned by the tastes and liberal attitude of patrons (including sophisticated churchmen) is already apparent in Gothic painting of the later Middle Ages, and culminates in what is known as the International Gothic style of the fourteenth century and the beginning of the fifteenth. Throughout Europe in France, Flanders, Germany, Italy and Spain, painters, freed from monastic disciplines, displayed the main characteristics of this style in the stronger narrative interest of their religious paintings, the effort to give more humanity of sentiment and appearance to the Madonna and other revered images, more individual character to portraiture in general and to introduce details of landscape, animal and bird life that the painter-monk of an earlier day would have thought all too mundane. These, it may be said, were characteristics also of Renaissance painting, but a vital difference appeared early in the fifteenth century. Such representatives of the International Gothic as Simone Martini (1285-1344) of the Sienese School of painting, and the Umbrian-born Gentile da Fabriano (c.1370-1427), were still ruled by the idea of making an elegant surface design with a bright, unrealistic pattern of colour. The realistic aim of a succeeding generation involved the radical step of penetrating through the surface to give a new sense of space, recession and three-dimensional form. This decisive advance in realism first appeared about the same time in Italy and the Netherlands, more specifically in the work of Masaccio (1401-28) at Florence, and of Jan van Eyck (c.1390-1441) at Bruges. Masaccio, who was said by Delacroix to have brought about the greatest revolution that painting had ever known, gave a new impulse to Early Renaissance painting in his frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine. See in particular: Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1425-6, Brancacci Chapel), and Holy Trinity (1428, Santa Maria Novella). The figures in these narrative compositions seemed to stand and move in ambient space; they were modelled with something of a sculptor's feeling for three dimensions, while gesture and expression were varied in a way that established not only the different characters of the persons depicted, but also their interrelation. In this respect he anticipated the special study of Leonardo in The Last Supper (1495-98, Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan). Though Van Eyck also created a new sense of space and vista, there is an obvious difference between his work and that of Masaccio which also illuminates the distinction between the remarkable Flemish school of the fifteenth century and the Italian Early Renaissance. Both were admired as equally 'modern' but they were distinct in medium and idea. Italy had a long tradition of mural painting in fresco, which in itself made for a certain largeness of style, whereas the Netherlandish painter, working in an oil medium on panel paintings of relatively small size, retained some of the minuteness of the miniature painter. Masaccio, indeed, was not a lone innovator but one who developed the fresco narrative tradition of his great Proto-Renaissance forerunner in Florence, Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337). See, for instance, the latter's Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes (c.1303-10, Padua). Florence had a different orientation also as a centre of classical learning and philosophic study. The city's intellectual vigour made it the principal seat of the Renaissance in the fifteenth century and was an influence felt in every art. Scholars who devoted themselves to the study and translation of classical texts, both Latin and Greek, were the tutors in wealthy and noble households that came to share their literary enthusiasm. This in turn created the desire for pictorial versions of ancient history and legend. The painter's range of subject was greatly extended in consequence and he now had further problems of representation to solve. In this way, what might have been simply a nostalgia for the past and a retrograde step in art became a move forward and an exciting process of discovery. The human body, so long excluded from fine art painting and medieval sculpture by religious scruple - except in the most meagre and unrealistic form - gained a new importance in the portrayal of the gods, goddesses and heroes of classical myth. Painters had to become reacquainted with anatomy, to understand the relation of bone and muscle, the dynamics of movement. In the picture now treated as a stage instead of a flat plane, it was necessary to explore and make use of the science of linear perspective. In addition, the example of classical sculpture was an incentive to combine naturalism with an ideal of perfect proportion and physical beauty. Painters and sculptors in their own fashion asserted the dignity of man as the humanist philosophers did, and evinced the same thirst for knowledge. Extraordinary indeed is the list of great Florentine artists of the fifteenth century and, not least extraordinary, the number of them that practised more than one art or form of expression.

The equation of the philosophy of Plato and Christian doctrine in the academy instituted by Cosimo de' Medici seems to have sanctioned the division of a painter's activity, as so often happened, between the religious and the pagan subject. The intellectual atmosphere the Medici created was an invigorating element that caused Florence to outdistance neighbouring Siena. Though no other Italian city of the fifteenth century could claim such a constellation of genius in art, those that came nearest to Florence were the cities likewise administered by enlightened patrons. Ludovico Gonzaga ( 1414-78) Marquess of Mantua, was a typical Renaissance ruler in his aptitude for politics and diplomacy, in his encouragement of humanist learning and in the cultivated taste that led him to form a great art collection and to employ Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) as court painter. Of similar calibre was Federigo Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. Like Ludovico Gonzaga, he had been a pupil of the celebrated humanist teacher, Vittorino da Feltre, whose school at Mantua combined manly exercises with the study of Greek and Latin authors and inculcated the humanist belief in the all-round improvement possible to man. At the court of Urbino, which set the standard of good manners and accomplishment described by Baldassare Castiglione in Il Cortigiano, the Duke entertained a number of painters, principal among them the great Piero della Francesca (1420-92). The story of Renaissance painting after Masaccio brings us first to the pious Fra Angelico (c.1400-55), born earlier but living much longer. Something of the Gothic style remains in his work but the conventual innocence, which is perhaps what first strikes the eye, is accompanied by a mature firmness of line and sense of structure. This is evident in such paintings of his later years as The Adoration of the Magi now in the Louvre and the frescoes illustrating the lives of St. Stephen and St. Lawrence, frescoed in the Vatican for Pope Nicholas V in the late 1440s. They show him to have been aware of, and able to turn to advantage, the changing and broadening attitude of his time. See also his series of paintings on The Annunciation (c.1450, San Marco Museum). His pupil Benozzo Gozzoli (c.1421-97) nevertheless kept to the gaily decorative colour and detailed incident of the International Gothic style in such a work as the panoramic Procession of the Magi in the Palazzo Riccardi, Florence, in which he introduced the equestrian portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici. Nearer to Fra Angelico than Masaccio was Fra Filippo Lippi (c.1406-69), a Carmelite monk in early life and a protege of Cosimo de' Medici, who looked indulgently on the artist's various escapades, amorous and otherwise. Fra Filippo, in the religious subjects he painted exclusively, both in fresco and panel, shows the tendency to celebrate the charm of an idealized human type that contrasts with the urge of the fifteenth century towards technical innovation. He is less distinctive in purely aesthetic or intellectual quality than in his portrayal of the Madonna as an essentially feminine being. His idealized model, who was slender of contour, dark-eyed and with raised eyebrows, slightly retrousse nose and small mouth, provided an iconographical pattern for others. A certain wistfulness of expression was perhaps transmitted to his pupil, Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510). In Botticelli's paintings, much of the foregoing development of the Renaissance is summed up. He excelled in that grace of feature and form that Fra Filippo had aimed to give and of which Botticelli's contemporary, Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-94), also had his delightful version in frescoes and portraits. He interpreted in a unique pictorial fashion the neo-Platonism of Lorenzo de Medici's humanist philosophers. The network of ingenious allegory in which Marsilio Ficino, the tutor of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici (a cousin of Lorenzo the Magnificent), sought to demonstrate a relation between Grace, Beauty and Faith, has equivalent subtlety in La Primavera (c.1482-3, Uffizi) and the Birth of Venus (c.1484-6, Uffizi) executed for Lorenzo's villa. The poetic approach to the classics of Angelo Poliziano, also a tutor of the Medici family, may be seen reflected in Botticelli's art. Though his span of life extended into the period of the High Renaissance, he still represents the youth of the movement in his delight in clear colours and exquisite natural detail. Perhaps in the wistful beauty of his Aphrodite something may be found of the nostalgia for the Middle Ages towards which, eventually, when the fundamentalist monk Savonarola denounced the Medici and all their works, he made his passionate gesture of return. The nostalgia as well as the purity of Botticelli's linear design, as yet unaffected by emphasis on light and shade, made him the especial object of Pre-Raphaelite admiration in the nineteenth century. But, as in other Renaissance artists, there was an energy in him that imparted to his linear rhythms a capacity for intense emotional expression as well as a gentle refinement. The distance of the Renaissance from the inexpressive calm of the classical period as represented by statues of Venus or Apollo, resides in this difference of spirit or intention even if unconsciously revealed. The expression of physical energy which at Florence took the form, naturally enough, of representations of male nudes, gives an unclassical violence to the work of the painter and sculptor Antonio Pollaiuolo (1426-98). Pollaiuolo was one of the first artists to dissect human bodies in order to follow exactly the play of bone, muscle and tendon in the living organism, with such dynamic effects as appear in the muscular tensions of struggle in his bronze of Hercules and Antaeus (Florence, Bargello) and the movements of the archers in his painting The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian (NG, London). The same sculptural emphasis can be seen in frescoes by the lesser-known but more influential artist Andrea del Castagno (c.1420-57). Luca Signorelli (c.1441-1523), though associated with the Umbrian School as the pupil of Piero della Francesca, was strongly influenced by the Florentine Pollaiuolo in his treatment of the figure. With less anatomical subtlety but with greater emphasis on outward bulges and striations of muscle and sinew, he too aimed at dynamic effects of movement, obtaining them by sudden explosions of gesture. It was a direction of effort that seems to lead naturally and inevitably to the achievement of Michelangelo (1475-1654). Though there are manifest differences in mode of thought and style between his Last Lodgement in the Sistine Chapel and Signorelli's version in the frescoes in Orvieto Cathedral, they have in common a formidable energy. It was a quality which made them appear remote from the balance and harmony of classical art. Raphael (1483-1520) was much nearer to the classical spirit in the Apollo of his Parnassus in the Vatican and the Galatea in the Farnesina, Rome. One of the most striking of the regional contrasts of the Renaissance period is between the basically austere and intellectual character of art in Tuscany in the rendering of the figure as compared with the sensuous languor of the female nudes painted in Venice by Giorgione (1477-1510) and Titian (c.1485-1576). (For more, please see: Venetian Portrait Painting c.1400-1600.) Though even in this respect Florentine science was not without its influence. The soft gradation of shadow devised by Leonardo da Vinci to give subtleties of modelling was adopted by Giorgione and at Parma by Antonio Allegri da Correggio (1489-1534) as a means of heightening the voluptuous charm of a Venus, an Antiope or an Io. The Renaissance masters not only made a special study of anatomy but also of perspective, mathematical proportion and, in general, the science of space. The desire of the period for knowledge may partly account for this abstract pursuit, but it held more specific origins and reasons. Linear perspective was firstly the study of architects in drawings and reconstructions of the classical types of building they sought to revive. In this respect, the great architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) was a leader in his researches in Rome. In Florence he gave a demonstration of perspective in a drawing of the piazza of San Giovanni that awakened the interest of other artists, his friend Masaccio in particular. The architect Leon Battista Alberti (1404-72) was another propagator of the scientific theory. Painters concerned with a picture as a three-dimensional illusion realized the importance of perspective as a contribution to the effect of space - an issue which involved techniques of illusionistic mural painting such as quadratura, first practised by Mantegna at the Ducal Palace in Mantua in his Camera degli Sposi frescoes (1465-74). Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was one of the earl promoters of the science at Florence. His painting of the Battle of San Romano in the National Gallery, London, with its picturesqueness of heraldry, is a beautifully calculated series of geometric forms and mathematical intervals. Even the broken lances on the ground seem so arranged as to lead the eye to a vanishing point. His foreshortening of a knight prone on the ground was an exercise of skill that Andrea Mantegna was to emulate. It was Mantegna who brought the new science of art to Venice. In the complex interchange of abstract and mathematical ideas and influences, Piero della Francesca stands out as the greatest personality. Though an Umbrian, born in the little town of Borgo San Sepolcro, he imbibed the atmosphere of Florence and Florentine art as a young man, when he worked there with the Venetian-born Domenico Veneziano (c.1410-61). Domenico had assimilated the Tuscan style and had his own example of perspective to give, as in the beautiful Annunciation now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, though Piero probably gained his scientific attitude towards design from the three pioneers of research, Brunelleschi, Alberti and Donatello (1386-1466), the greatest sculptor in quattrocento Florence. Classical in ordered design and largeness of conception, but without the touch of antiquarianism that is to be found in Mantegna, Piero was an influence on many painters. His interior perspectives of Renaissance architecture which added an element of geometrical abstraction to his figure compositions were well taken note of by his Florentine contemporary, Andrea del Castagno (c.1420-57). A rigidly geometrical setting is at variance with and yet emphasizes the flexibility of human expression in the Apostles in Andrea's masterpiece The Last Supper in the Convent of Sant' Apollonia, Florence. Antonello da Messina (1430-1479) who introduced the Flemish technique of oil painting to Venice brought also a sense of form derived from Piero della Francesca that in turn was stimulating in its influence on Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516), diverting him from a hard linear style like that of Mantegna and contributing to his mature greatness as leader of Venetian Painting, and the teacher of Giorgione and Titian. Of the whole wonderful development of the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were the heirs. The universality of the artist was one crucial aspect of the century. Between architect, sculptor, painter, craftsman and man of letters there had been no rigid distinction. Alberti was architect, sculptor, painter, musician, and writer of treatises on the theory of the arts. Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-88), an early master of Leonardo, is described as a goldsmith, painter, sculptor and musician: and in sculpture could vie with any master. But Leonardo and Michelangelo displayed this universality to a supreme degree. Leonardo, the engineer, the prophetic inventor, the learned student of nature in every aspect, the painter of haunting masterpieces, has never failed to excite wonder. See, for instance, his Virgin of the Rocks (1483-5, Louvre, Paris) and Lady with an Ermine (1490, Czartoryski Museum, Krakow). As much may be said of Michelangelo, the sculptor, painter, architect and poet. The crown of Florentine achievement, they also mark the decline of the city's greatness. Rome, restored to splendour by ambitious popes after long decay, claimed Michelangelo, together with Raphael, to produce the monumental conceptions of High Renaissance painting: two absolute masterpieces being Michelangelo's Genesis fresco (1508-12, Sistine Chapel ceiling, Rome), which includes the famous Creation of Adam (1511-12), and Raffaello Sanzio's Sistine Madonna (1513-14, Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden). In addition, both artists were appointed architect-in-charge of the new St Peter's Basilica in Rome, a symbol of the city's transformation from medieval to Renaissance city. Leonardo, absorbed in his researches was finally lured away to France. Yet in these great men the genius of Florence lived on. For the story of the Late Renaissance, during the period (c.1530-1600) - a period which includes the greatest Venetian altarpieces as well as Michelangelo's magnificent but foreboding Last Judgment fresco on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel - see: Mannerist Painting in Italy. See also: Titian and Venetian Colour Painting c.1500-76. Best Collections of Renaissance Art The following Italian galleries have major collections of Renaissance paintings or sculptures. • Uffizi

Gallery (Florence) |

|

• For more about the Florentine, Roman or Venetian Renaissance, see: Visual Arts Encyclopedia. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ART |