Representational Painting (Ireland)

Realistic Style of Painting Which Depicts

Recognizable Objects.

MAIN A-Z INDEX - A-Z of IRISH ART

|

Representational Painting (Ireland) |

Le Petit Dejeuner by Sarah Purser. |

Representational Painting in IrelandThe relative lack of patronage for visual art in Ireland during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries led to the emergence of three separate traditions, of representational art. At home, at least from 1800 onwards, Irish painters depended upon a meagre distribution of religious or official commissions, augmented by private patronage devoted to portraiture, Irish landscapes and sundry other works. This group included painters like the genre artist James Brenan (1837–1907) and the portraitist Sarah Purser (1848-1943). But the scarcity of resources and its consequent restraint on the growth of indigenous art in Ireland can be gauged from the surprising lack of interest in depicting the Great Famine during the late 1840s. |

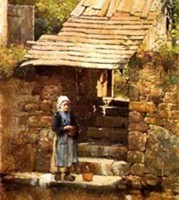

A Street in Brittany. (1881). By Stanhope Forbes. |

Abroad, Irish artists fared better. A number developed successful careers in London, largely as portraitists. After Martin Archer Shee (1769-1850), a Dubliner who later became President of the London Royal Academy, the best example was the great William Orpen (1878-1931), whose professionalism and technical virtuosity influenced Irish artists for decades to come. The history painter Daniel Maclise (1806-70) was another great Irish artist who found success in London, as did townscape painter Rose Maynard Barton (1856-1929). The third group went to the Continent, usually to study (in centres like Antwerp or Paris), and afterwards many of them joined one of several artistic communes - like Barbizon, Pont-Aven, Grez-sur-Loing, or Concarneau. Here they absorbed the prevailing doctrines of Realism and Impressionism, as well as the techniques of plein-air painting. |

Breton Girl By A River. By Walter Osborne. |

ABSTRACT ART |

Such artists included the tonal expert Nathaniel Hone the Younger (1831-1917), the rural artist Augustus Nicholas Burke (1838-91), the orientalist Aloysius O'Kelly (1853-c.1941), the romantic Frank O'Meara (1853-88), the colourists Roderic O'Conor (1861-1940) and William John Leech (1881-1968), the Impressionists Walter Osborne (1859-1903) and John Lavery (1856-1941), the classical Dermod O'Brien (1865-1945), as well as Stanhope Forbes (1857-1947) and Norman Garstin (1847-1926) who were important members of the Newlyn School of landscape art. Early 20th Century The growth of nationalist feeling and associated political developments in Ireland during the first quarter of the 20th century led to the return of many expatriate artists, such as the landscape painter Paul Henry (1876-1958), the genre-painter and portraitist Richard Moynan (1856-1906) and the Impressionist John Lavery. (For some of the most highly valued art of this era, see: Most Expensive Irish Paintings.) |

|

In addition, the emergence of the new Free State triggered a renewed interest and investment in Irish art, especially education. During the 1900s, the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art was enlarged to include classes in enamels, metalwork, stained glass, plus a life class, taught initially by William Orpen. In 1924, the school was taken over by the Department of Education and twelve years later it became the National College of Art with teaching faculties of painting, sculpture and design. Traditional Academic Approach to Art Even so, despite this short-lived renaissance, the Irish art world remained highly conservative, ruled as it was from Dublin, which remained relatively parochial and considerably behind the times. Thus, despite the foundation of the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art by Hugh Lane, as far back as January 1908, its collection was (by French standards) several decades out of date. |

|

In addition, a preoccupation with developing an 'Irish' style of painting and sculpture tended to exclude interest in the new Cubist and Expressionist art movements which were all the rage on the Continent. The new Irish arts establishment promoted a traditional academic approach to oil painting (as exemplified by outstanding painters such as Sean Keating (1889-1977), Leo Whelan (1892-1956), James Sleator (1889-1950), Diarmuid O'Brien (1865-1945), and Maurice MacGonigal (1900-1979)), with little tolerance for non-representationalism. In 1923, when Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone staged one of the first abstract painting exhibitions seen in Ireland at the Society of Dublin Painters, critics were horrified at the show's absence of realism. Artist Reaction The pressure on Irish artists to conform with the dominant traditionalist viewpoint was immense. Many were dependent on teaching posts within the education system; many were dependent on the annual Exhibition of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) to promote their name and works. And since both establishments were controlled by traditionalists, artists had little choice but to toe the line. Until 1943, that is, when a group of mostly upper-middle class Dublin artists - including Norah McGuinness (1901-1980), Mainie Jellett (1897-1944), Evie Hone (1894–1955), Fr Jack Hanlon (1913-1968), Louis le Brocquy (1916-2012), and Margaret Clarke (1888-1961) - founded the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA). Its annual show was a forum for new styles of Irish painting which were generally less academic, less representational and more modernist than those favoured by the traditionalists. Despite its different approach however, many Irish painters and sculptors exhibited their works both in traditional forums like the RHA as well as the IELA. Later 20th Century If the IELA helped to broaden the general arts curriculum and offer new opportunities to both artists and the general public, it had little power to improve the overall financial or political climate. Thus, despite some improvements - like the setting up of the Irish Arts Council in 1951 - the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s were dominated by economic stagnation and political unrest in the North. Against this backdrop, in 1971, the National College of Art and Design (the successor to the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art) was restructured to liberalize its operation, and in 1973, after three decades of effort, the committee of the IELA decided to hand over to a completely new committee of younger artists, in order to continue the task of embracing new art-forms, especially non-representational. However, the representational tradition has been maintained by a small number of individuals including the Impressionist Norman Teeling (b.1944) the figurative and landscape painter Martin Gale (b.1949), the classical landscape artists Niccolo D'Ardia Caracciolo (1941-1989) and Martin Mooney (b.1960), as well as the the classical realists Mark O'Neill (b.1963) and Conor Walton (b.1970). Other leading representational artists of the late 20th century include the portraitist David Nolan (b.1966), the Impressionist seascape painter John Morris (b.1958), and the landscape artists Paul Kelly (b.1968) and Henry McGrane (b.1969). Representational Art in the 21st Century During the last century, the importance of representational art in Ireland swung like a pendulum. In the early days it was wholly dominant, and was seen by traditionalists as the 'only' acceptable form of fine art. As the century developed, its importance began to decrease as more modern styles started to emerge under the wing of the IELA. Latterly, due to increasing prosperity and greater investment in the arts infrastructure, as well as greater liberalization in art schools, representationalism is starting to lose its appeal among both artists and art-professionals. Despite this, representational painting and sculpture remains the most sought-after type of artwork among both collectors and the general public. Why is Representational Art Losing its Appeal? There seems to be no obvious reason for this, although a number of contributory factors suggest themselves. More Challenging For Art Students More Numerous Applications A New Class of Art-Administrators More money and more education should, in theory, lead to better art for the general public. Whether this is in fact happening only time will tell. Meanwhile, the importance of representational art continues to decline, with unknown consequences for us all. NEW ART CLUB: The Oil Painters of Ireland Artists or art-lovers who enjoy traditional representational oil painting, in the form of portraiture, landscapes, seascapes or genre-scenes, should check out a new group called Oil Painters of Ireland. |

|

• For more info about painters and

sculptors from the 32 counties, see: Irish

Artists. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ART |