Irish Art After the Middle Ages

Artworks in Ireland After the Medieval

Era.

![]()

![]()

|

Irish Art After the Middle Ages |

12th Century High Cross Sculpture of Roscrea, Co Tipperary See also: Medieval Sculpture. |

Post-Renaissance (and later)As a whole, the Middle Ages (c.1000-1450) and later centuries incorporating the Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo and Neo-Classical styles of painting and sculpture, was a relatively dormant period in the history of Irish art. Although Celtic art (eg. knotwork patterns) was noticed by certain Renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci, the impact of Irish culture on the great European art movements of the period was minimal, and for good reason. After the Norman invasion of England in 1066, Ireland together with its Celtic neighbours in Wales and Scotland was constantly pressurized by Anglo-Norman barons and the forces of the English Crown, leading to a suppression of Irish cultural life as well as the dissolution of the monasteries - themselves a bastion of Irish Christian culture. |

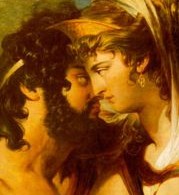

Detail from Jupiter & Juno on Mount Ida, by 18th Century Cork Neo-Classical Historical Painter James Barry. |

|

HISTORICAL IRISH MONUMENTS |

Not surprisingly, all three Celtic countries experienced severe social and economic difficulties during the 1600s, 1700s and 1800s, culminating in the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s. Many people from Ireland emigrated to the United States and Australia, or moved to the industrial cities of Britain in search of food and work, leading to a consequent decline in Irish culture and language. For example, while most native Irish people spoke Irish until the early nineteenth century, by 1891, 84 percent of Irish people only spoke English. Even so, Irish culture never disappeared. While the dissolution of the (Catholic) monasteries severely diminished the role of the Church as a patron of Irish arts, it was followed by the emergence of numerous guilds of craftworkers, from whom new generations of Anglo-Irish aristocracy and prosperous merchants commissioned works of art (portraits and landscapes). For example, a painters' guild was set up in 1670, whose members included such artists as Garret Morphy and James Latham, while other decorative craftsmen such as goldsmiths, silversmiths, and stained glass workers also established their own guilds and gradually began to prosper. The visual arts in Ireland also benefited during the eighteenth century, from the twin effects of growing prosperity (among the ruling classes) and the influence of the European Enlightenment which led to the construction of a number of public buildings of noted architectural style, such as the Custom House and Four Courts (architect James Gandon) and the Parliament House, now the Bank of Ireland (architect Edward Lovett Pearce). (For a pictorial view of Dublin's architecture in 1800, see the outstanding aquatint engravings by James Malton). New cultural institutions, such as the Royal Dublin Society (founded 1731) and the Royal Irish Academy (founded 1785) were established. Meanwhile, eighteenth century Irish artists like George Barret Senior (1732-84) and James Barry (1741-1806) began to include new ideas (eg. from the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke) in their paintings using classical and mythological allusions. |

|

However, despite this gradual rise in Irish culture, the arts in Ireland were chiefly the preserve of the rich aristocracy. Irish painting and Irish sculpture was created for a relatively small clientele by artists who, in their attempt to please their patrons, rarely sought inspiration from Ireland's Celtic artistic traditions. As the country passed into the nineteenth century, a growing demand for self-rule, if not outright independence, began to be heard throughout the land. Over the next century this would lead to the establishment of the Irish State (1921) and the emergence of new creative forms which more accurately reflected the culture of Ireland. |

|

• For information about the cultural

history of Ireland during the Middle Ages, see: Irish

Art Guide. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF IRISH AND CELTIC ART |