History of Irish Art

Origins and Evolution of Visual Arts in

Ireland.

MAIN A-Z INDEX - A-Z of IRISH ART

|

History of Irish Art |

|

IRISH SCULPTURE IRISH PAINTERS &

SCULPTORS |

History of Irish Visual Arts (3300 BCE-Present)The 10 Key Stages • Newgrange (3300

BCE) |

|

IRISH PAINTING |

|

IRISH

HISTORICAL MONUMENTS |

Untouched by the wave of Upper Paleolithic cave painting, sculpture and carvings which swept Stone Age Europe (40,000-10,000 BCE), Ireland received its first visitors around 6,000 BCE, or slightly earlier. But the actual history of visual arts in Ireland begins with the Neolithic stone carvings discovered at the Newgrange megalithic tomb, part of the Bru na Boinne complex in County Meath. This superb example of Irish Stone Age art was built between c.3300-2900 BCE: five centuries before the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt, as well as the Stonehenge stone circle in England. As well as a variety of megalithic art, including a number of intricate spiral engravings, Newgrange features what archeologists believe to be the first recorded map of the moon. These magnificent petroglyphs at Newgrange and at the Knowth megalithic tomb exemplify a particularly sophisticated form of ceremonial and funerary architecture of the late Stone Age, and are among the finest known examples of Neolithic art in Europe. However, little is known about the precise function of these prehistoric structures or the identity of their builders, except that their construction suggests a relatively integrated and cohesive social environment. A second contemporary type of Neolithic necropolis - the long barrow - is also found in Stone Age Ireland, but its design is more primitive and required far less organization. |

|

QUESTIONS ABOUT ART IN

IRELAND |

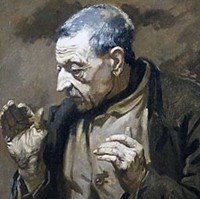

The Flycatcher. By William Orpen, the greatest of all Irish portrait artists. |

Art During the Bronze Age and Iron Age During the succeeding period of Bronze Age art in Ireland (c.3000-1200 BCE), there is evidence of artifacts from the Beaker culture (named after the shape of its pottery drinking vessels), along with a series of wedge tombs. In addition, Irish craftsmen developed a flourishing metal industry, fashioning a variety of gold, bronze and copper objects. This era also witnessed a significant growth in trade between Ireland and Britain, as well as Northern Europe including Germany and the Nordic countries. The Iron Age in Ireland (roughly 1500-200 BCE), characterized by the production iron tools and weapons, was heavily influenced in its final centuries (from roughly 400 BCE onwards) by the arrival of the Celts who were master goldsmiths and blacksmiths. Their arts and crafts belong however to the more elaborate and curvilinear idiom of La Tene Celtic art, which superceded the earlier Hallstatt culture. It was these Celtic designs - notably the Celtic spiral designs, the intricate Celtic interlace patterns and of course the Celtic crosses - that would inspire the next three major achievements in Irish visual art. |

|

Articles Wanted |

2. Celtic Metalwork and Stone Sculpture (400 BCE - 800 CE) Unlike Britain and the Continent, Ireland's geographic remoteness prevented colonization by Rome. Thus, despite regular trade with Roman Britain, the country became a haven for the uninterrupted development of Celtic art and crafts, which were neither displaced by Greco-Roman art, nor destroyed in the ensuing "Dark Ages" (c.400-800) when Roman power in Europe was replaced by barbarian anarchy. This led to an unbroken tradition of Celtic culture which retained its own oral, historical and mythological traditions, as exemplified in the Lebor Gabala Erenn (Book of Invasions). It was this Celtic culture with its tradition of metallurgical craftsmanship and carving skills, (see Celtic Weapons art) that was responsible for the second great achievement of Irish art: a series of exceptional items of precious metalwork made for secular and Christian customers, (see also Celtic Christian art) as well as a series of intricately engraved monumental stoneworks. |

|

|

• Celtic metalwork art produced in Ireland is first exemplified by items like the Petrie Crown (c.100 BCE - 200 CE), and the Broighter Gold Collar (1st century BCE), and by the later Tara Brooch (c.700 CE). (See also Celtic Jewellery art.) Similar designs can also be seen in several masterpieces of early Christian art (c.500-900 CE) such as the Derrynaflan Chalice (c.650-1000), the gilt-bronze Crucifixion Plaque of Athlone (8th century CE) the Moylough Belt Shrine (8th century CE), the Ardagh Chalice (8th/9th century CE), as well as processional crosses like the Tully Lough Cross (8th/9th century CE), and the Cross of Cong (c.1125 CE) made for King Turlough O'Connor. Many of these treasures can be viewed in the National Museum of Ireland. • Celtic stonework is best exemplified by the granite Turoe Stone monumental pagan sculpture (c.150-250 BCE), discovered in County Galway. See also Celtic Sculpture.

Impact of Christianity on Irish Art With much of Europe experiencing a cultural stagnation due to the chaos and uncertainty which prevailed after the fall of Rome and the onset of the Dark Ages, the Church authorities selected Ireland as a potential base for the spread of Christianity and around 450 CE despatched St Patrick in the role of missionary. His success, and that of his followers (St Patrick, St. Brigid, St Enda, St Ciariana, St Columcille et al), led to the Christianization of Ireland and, crucially, to the establishment of a series of monasteries, which acted as centres of learning and scholarship in both religious and secular subjects and which paved the way for the next great milestone in Irish visual art. |

|

3. Illuminated Manuscripts (c.650-1000) The third great achievement of Irish art was the production of a series of ever more magnificent illuminated manuscripts, consisting of intricately illustrated Biblical art with lavishly decorated panels (occasionally whole "carpet" pages) of Celtic-style animal or ribbon interlace, spirals, knotwork, human faces, animals, and the like, all executed with the utmost precision and sometimes embellished with precious metals like gold and silver leaf. See, for instance, Christ's Monogram Page in the Book of Kells. Created in the scriptoriums of monasteries like Clonmacnoise and Durrow (Co Offaly), Clonard and Kells (Co Meath), among many others, these fabulous examples of Irish monastic art were a mixture of Christian calligraphic skills and Celtic artwork, with additional Saxon/Germanic designwork, such as tracery. They are regarded by historians as being among the greatest artworks of the medieval period in Europe. |

|

|

Famous Irish Biblical manuscripts (illustrated with Celtic interlace, knotwork and spiral designs) include the Cathach of St. Columba (early 7th century), the Book of Durrow (c.670), the Lindisfarne Gospels (c.698-700), and the Book of Kells (c.800). See also: History of Illuminated Manuscripts (600-1200). These works can be viewed at Trinity College Dublin Library or the Royal Irish Academy. These biblical treasures gave rise to a gradual but significant renaissance in Irish art (sometimes called Hiberno-Saxon style or Insular art), which spread via the monastic network to Iona, Scotland, Northern England and the Continent. By the 12th century, there was hardly a Royal court in Western Europe that did not have an Irish adviser on cultural affairs. Meanwhile, Irish monasteries continued to play an active part in the cultural life of the country into the late 12th century and beyond. In addition to their role as centres of religious devotion and Christian art, they invested significantly in ecclesiastical icons, such as the above-mentioned chalices (Derrynaflan, Ardagh), shrines and processional crosses, the production of which required the maintenance of a busy forge and blacksmithery, and the retention of numerous craftsmen. Finally, as well as a busy scriptorium (for illuminated manuscripts) and forge (for precious metalwork), from around 750 onwards monasteries also paid for an important program of biblical sculpture which was to become the next great achievement of Irish art. |

|

|

4. High Cross Sculpture (c.750-1150) The fourth great achievement of Irish art was religious stonework. During the period 750-1150, Irish sculptors working within monasteries created a series of Celtic High Cross Sculptures which constitute the most significant body of free-standing sculpture produced between the collapse of the Roman Empire (c.450) and the beginning of the Italian Renaissance (c.1450). This High Cross sculpture represents Ireland's major sculptural contribution to the history of art. The ringed High Crosses fall into two basic groups, depending on the type of engravings and relief-work displayed. The first group, dating largely from the 9th century, is decorated exclusively with abstract interlace ornament, Ultimate La Tene animal interlace, as well as key- and fret-patterns. The second group consists of crosses with narrative scenes from the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, although these are often ornamented with bossed fleshy scrolls, as on the 10th century Muiredach's Cross, at Monasterboice.

Irish Art Stagnates (c.1200-1700) The period 1200-1700 witnessed a great deal of history in Ireland but little cultural activity. As a result, Irish art after the Middle Ages underwent five centuries of stagnation. The impact of this "dead" period - caused mainly by the colonial ambitions of first Norman, then British and later Scottish settlers - cannot be overestimated. It severed Irish culture from the influence of Renaissance art and consigned the country to a state of cultural isolation from which (arguably) it has only recently emerged. At any rate, since the 12th century, Ireland has produced no further major contributions to European visual art to rival its earlier achievements. 5. Painting: The Rebirth of Irish Art (1650-1830) This period witnessed the first green shoots of an artistic recovery. Increased prosperity during the early 18th century led to the formation of a number of new cultural institutions, such as the Royal Dublin Society (started 1731) and the Royal Irish Academy (founded 1785). Meantime, a number of talented artists began to appear from the late 17th century onwards. In keeping with the demands of the time, the main area of activity was fine art painting, notably portraiture and landscapes. This artistic recovery continued into the nineteenth century with the establishment of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) in 1823, and the expansion of the Royal Dublin Society (founded 1731) and the Crawford College of Art, all of which helped to stimulate the fine art infrastructure in Ireland, especially for visual arts like painting. 18th Century Portrait Painting 18th Century Landscape Painting This artistic rebirth continued into the 19th century with the establishment in 1823 of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA), the expansion of the educational facilities of the Royal Dublin Society (later hived off to become the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art and ultimately the National College of Art and Design), and the refurbishment (1830-1884) of the Crawford College of Art (championed by James Brenan and financed by Cork benefactor William Horatio Crawford), all of which helped to stimulate the fine art infrastructure in Ireland, especially for visual arts like painting. |

|

|

6. Irish Artists Emigrate (c.1830-1900) Despite this strengthening of the arts infrastructure and educational system, 19th century Irish art was marked by continual emigration. This was because patronage was scarce, and London - with its vastly larger art market, its art studios and career potential - was still the Mecca for talented Irish painters and sculptors. Among such emigrant artists, were the sculptors Patrick MacDowell (1799-1870), John Foley (1818-74), John Lawlor (1820-1901) and John Hughes (1865-1941), as well as the watercolourist Francis Danby (1793-1861) and the history painter and portraitist Daniel Maclise (1806-70). Later, they were followed to London by portraitists like the County Down-born John Butler Yeats (1839-1922), the academic style Gerald Festus Kelly (1879-1972) and William Orpen (1878-1931), all of whom made important contributions to Victorian art in a variety of genres. In contrast, many top Irish landscape painters spent long periods in France, working at Barbizon near Fontainebleu, or Pont-Aven and Concarneau in Brittany, where they absorbed the plein-air painting methods of the Impressionists. Such 'emigrants' included artists like: Augustus Nicholas Burke (1838-91), Frank O'Meara (1853-88), Aloysius O'Kelly (1853-1941), Sir John Lavery (1856-1941), Stanhope Forbes (1857-1947), Henry Jones Thaddeus (1859-1929), Walter Osborne (1859–1903), Joseph Malachy Kavanagh (1856-1918), Richard Thoman Moynan (1856-1906), Roderic O'Conor (1860–1940), Norman Garstin (1847-1926) and William Leech (1881-1968). See also: Plein-Air Painting in Ireland. This is not to underestimate the talents of indigenous Irish artists who remained in Ireland (or who returned from abroad), but the terrible trauma of the Great Famine (c.1845-50), the continuing political squabbles between the arts establishments in London and Dublin, plus the relative lack of commissions in Dublin (let alone in Cork, Galway and Limerick) compared to the commercial promise of London, and the plein-air weather of France, all added up to a powerful incentive to paint or sculpt overseas. An indigenous school of Irish painting was beginning to emerge, but it had yet to acquire critical mass, thus to a great extent, the history of Irish art during the 19th century was marked by the exodus abroad. (See also: 19th Century Irish Artists.) 7. The Growth of Indigenous Art (c.1900-40) Gradually, around the turn of the century, the beneficial effects of education, along with an increase in Dublin patronage, the efforts of Hugh Lane, and the impact of the Celtic Arts Revival movement, all led to the appearance of a new generation of indigenous Irish artists, such as George 'AE' Russell (1867-1935), Margaret Clarke (1888-1961), Sean Keating (1889-1977), James Sinton Sleator (1889-1950), Leo Whelan (1892-1956), and Maurice Macgonigal (1900-1979). This group, together with returning emigrant sculptors like John Foley and Oliver Sheppard (1864-1941), painters like the Irish genre artist Richard Thoman Moynan (1856-1906), the landscape artist Paul Henry, the expressionist Jack B Yeats (1871-1957), and the portraitist William Orpen (1878-1931) - who returned regularly to teach at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art - formed the nucleus of an active corps of local artists. To these, must be added a younger generation of more internationally minded Irish painters, including Mary Swanzy (1882-1978), Mainie Jellett (1897-1944) and Evie Hone (1894-1955), who introduced Cubism and other abstract art forms to Ireland during this time, forming the avant-garde Society of Dublin Painters in the process. A later addition to the group was the brilliant Francophile Louis le Brocquy (1916-2012). Twentieth century Irish art was further nourished by the establishment of the Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art (1908), and by the emergence of an independent Irish State in the early 1920s. However, if Independence led to an increase in state patronage for some sculptors and painters, it failed to trigger any general renaissance in the visual arts. There were fewer creative opportunities, for instance, in Irish sculpture: John Foley (1818-74) and later Albert Power (1881-1945) and Seamus Murphy (1907-75) were fully occupied with traditional statues and busts of eminent people of the day, rather than individual creativity. The decorative arts fared no better. In the area of stained glass, for example, despite the individual creative efforts of Harry Clarke (1889-1931), Sarah Purser (1848-43) and Evie Hone (1894-1955), the narrow-minded Irish government provided little help, even going so far as to reject some of Clarke's finest works for their excessive 'modernity.' Furthermore, in the two decades following Independence, power within the Irish arts establishment, notably the ruling committee of the Royal Hibernian Academy, was exercised by a conservative phalanx of traditionalists - drawn almost exclusively from the indigenous group of Irish artists - who resisted all attempts by more broad-minded individuals to align Irish art with 20th century European styles of painting and sculpture. This period drew to a close with the advent of World War II, which saw the issue of modernization emerge into the open. |

|

|

8. The Formation of the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (1943) The dreary 1940s witnessed a creative as well as a material decline in Irish visual art. Not only was patronage for the arts scarce, but the conservative Irish artistic establishment - represented by the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) - seemed unable to come to terms with European developments in art - such as Fauvism, Cubism, Dadaism, and Surrealism. And since they controlled the composition of the annual RHA exhibition (the main showcase for professional painters and sculptors in Ireland) they were able to reject works that did not fit in with their traditionalist concept of what art should be - an approach that provoked considerable opposition from the modernists. The conservatives were not ignorant of European developments in painting and sculpture, but they did not like what they saw, and hoped it would go away and that art would revert to the representationalist traditions of the Renaissance. Unfortunately, the heavy-handed way they implemented this viewpoint undermined its value. For example The Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art would hardly ever accept any work which was painted more recently than the time of Jean Baptiste Corot (1796-1875): thus for example they rejected a Rouault painting as blasphemous and a Henry Moore sculpture as obscene. By contrast the modernists sought not to break with traditional but rather to reach beyond it. Battle between the traditionalists and modernists errupted in 1942, following an outspoken attack on the RHA by Mainie Jellett, which caused its selection committee to reject "The Spanish Shawl" by Louis le Brocquy, and numerous other modern works. The 1942 rejection of Rouault's "Christ and the Soldier" by Dublin's Hugh Lane Gallery was another provocation. As a result, the following year a number of (largely) upper-middle class Dublin artists banded together and organized the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA), a new annual forum for painters and sculptors who did not agree with the "blinkered" vision of the Royal Hibernian Academy. Its stated mission was to make available a comprehensive survey of significant work, irrespective of School or manner, by living Irish artists." The main organizers of the IELA were Mainie Jellett (1897-1944), Evie Hone (1894–1955), Fr Jack Hanlon (1913-1968), Norah McGuinness (1901-1980), Louis le Brocquy (b. 1916), and Margaret Clarke (1888-1961). Later supporters included Patrick Scott (b.1921), Tony O'Malley (1913-2003), Camille Souter (b.1929) and Barrie Cooke (b.1931), and others. The IELA shows injected some visual excitement into the drabness of wartime Dublin and offered a welcome alternative to the more conservative RHA exhibitions. That said, many Irish artists exhibited in both. Even so, each represented different points of view. The RHA maintained what it believed to be 'the tradition' while the IELA was open to every new development. Even so, the formation of the IELA was no Bolshevik revolution. The rather parochial Dublin art world was home to a small number of important bodies such as the Royal Hibernian Academy, the Friends of the National Collections, the Haverty Trust, the Arts Advisory Committee for the Municipal Gallery, the Irish Exhibition of Living Art and so on. And both conservatives and modernists co-existed relatively happily on the same committees. Furthermore, the IELA was keenly aware that their aims would be unattainable without the cooperation of the National College of Art, and the RHA who dominated it, as well as the goodwill of the Director of the National Gallery and the President of the RHA. Instead, the emergence of the IELA should be seen as an assertion of the need for Ireland to embrace a wider concept of art - rather that one defined solely by its cultural roots. In a way, it let the cat out of the bag. Now, for instance, artists could explore abstract art without being accused of blasphemy! In this sense the IELA was a defining step in the development of the Irish school. 9. Modern Irish Art (1943-present) Despite the broadening of its outlook, Irish art during the four post-war decades was as much influenced by economic and political events at home, than by anything in the international art world. The drab 1950s led to further emigration by artists, while the excitement of the mid-1960s rapidly cooled with the onset of the 'Troubles' in the North, during the 1970s and 1980s, when politics dominated the headlines. Nevertheless, the next generation, which came to maturity in the mid-1960s was more open to international developments. They were also benefiting from the activities of a number of new Irish art organizations coming on stream. For example, the Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaion), founded in 1951, was purchasing works by Irish artists and distributing grants, as was its sister body in the North, the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA), now renamed the Arts Council of Northern Ireland; the Haverty Trust, the Oireachas Douglas Hyde Gold Medals, the generous Carroll's Prizes for works at the IELA shows, and the Belfast Open Competitions were dispersing financial rewards; there were exhibitions in London and (from 1967) Rosc exhibitions at the RDS. The Royal Hibernian Academy and the Royal Ulster Academy were ongoing showcases for native talent. The Hugh Lane Gallery (finally becoming a real gallery of Modern Art), the National Gallery, the Ulster Museum of Fine Arts, as well as innovative Irish art galleries like the Dawson and David Hendricks Gallery, were introducing artists to international works; and Irish painters and sculptors were being selected for biennales in Venice, Paris - and winning awards. |

|

The Postmodernist Revolution 1970s Meantime, in 1973, the ruling committee of the IELA decided to hand over to an entirely new committee of younger artists in order to maintain the organization's contemporary impact. The Irish crafts industry also received an upgrade with the establishment of the Crafts Council of Ireland in 1971. 1980s Other developments during the 1980s included: the establishment of the National Self-Portrait Collection (1980); the formation of the Sculptors’ Society of Ireland (1980) (now Visual Artists Ireland); the foundation of Aosdana (1981), the elite group of creative practitioners in Ireland; the launching of CIRCA (1981), Ireland's premier journal of contemporary visual arts; and the foundation of the National Sculpture Factory (NSF) in Cork in 1989. 1990s Some Thoughts About Irish Art Styles & Themes We don't tend to analyze music. Either we like the sound of it, or we don't. But if we judge a painting purely on its visual appearance we get accused of being (at best) a philistine or (at worst) an idiot. And as an Art Editor, I have to sound extra knowledgable, which frankly is a real pain, because I'm not. And to prove it, here are some of my thoughts on Irish art of the mid-20th century onwards. At least it gives me the opportunity to mention some wonderful artists. There has never been a specific style of Irish painting, or sculpture. True, certain landscapes, human figures and national heroes have attracted regular attention, but one would be hard pressed to find anything in common between (say) Paul Henry, Francis Bacon, William Orpen and Sean Scully. The best we can do is identify certain approaches and the artists associated with them. Abstract Art Representational Art Primitivism Romanticism Nationalism Other Styles

The turn of the century saw the Irish art market soar to new heights. Although the commercial value of top Irish artists had jumped significantly during the 1990s, the new Millennium saw Francis Bacon smash the world record for the most expensive work of contemporary art (his Triptych, 1976, sold for $86.3 million at Sothebys New York, in 2008), while six other Irish painters broke the million euro barrier: • William

Orpen (1878-1931) These records reflected a surprising but unmistakable degree of confidence in the value of Irish art, and gave a considerable boost to the market value of less famous artists. With Sothebys already established in Dublin, along with indigenous auction houses like Adams, deVeres and Wytes, and others, the city became an important venue for sales of Irish painting and sculpture - which, like house prices, seemed to defy gravity. (For more details about the highest priced artworks, see: Most Expensive Irish Paintings.) At the same time, the arts industry on the island of Ireland - with thousands of employees spread across two government departments, two Arts Councils, numerous other state-run or state-sponsored bodies and magazines, artists groups such as Aosdana and Visual Artists Ireland, and a large network of national museums, art centres and commercial galleries - continued to expand to cater for the increased demand. Unfortunately, in 2008, the bubble burst, leaving Ireland's cultural revival under severe financial pressure in the wake of the recent worldwide recession. At present, an estimated 83 percent of Irish creative practitioners remain dependent upon the income of their partners, and the situation is likely to worsen in view of the 18.5 percent cutback in the current art budget. Even so, with full-time arts officers in almost all of the 32 counties of Ireland, a multi-million euro budget, and a talented pool of contemporary Irish artists, the long-term future of Irish art could hardly be brighter, at least when compared to previous eras of emigration and financial struggle. In any event, it's worth remembering that the successful development of visual art (in Ireland or elsewhere), while related to financial prosperity, is rarely defined by it. The Medici family dynasty may have bankrolled the Italian Renaissance in Florence, but their money would have been useless without the native talents of Brunelleschi, Donatello, Masaccio and others. So the future of Irish art is, as always, in the hands of its artists, teachers and pupils. Will they succeed in creating relevant works of art that interest the public at large? Will they be able to maintain (and hopefully improve on) the great traditions of Western painting and sculpture? Only time will tell. One thing is for sure. If Irish art colleges attach too much importance to subjective "creativity" - and recent graduate shows are not reassuring in this respect - we are likely to lose the necessary skill-base needed to create lasting works of art. Ephemeral art (which accords less value to the finished product than the idea behind it) may be high fashion in artistic circles, and may even resonate with a public beguiled by TV shows like "Big Brother", but it has no lasting value. After all, cultures and civilizations are not judged by the brilliant ideas they may have had, but by what they leave behind them. |

|

• For more about the origins and evolution of painting and sculpture in Ireland, see: Homepage. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ART |