Tully Lough Cross

History, Description, Origin, Co Roscommon,

Hiberno-Saxon Insular Art.

![]()

|

Tully Lough Cross |

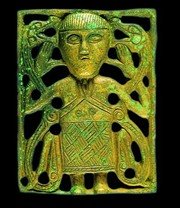

Detail from the Tully Lough Cross. A gem of Celtic Metalwork art of the eighth/ninth century CE. |

Tully Lough CrossThis exquisite item of religious art is a rare example of an Irish altar cross of the 8th/9th century CE, made out of metal bronze sheets enclosing a wooden core, and decorated in ultimate La Tene style. Like many artifacts made during the era of early Christian art in Ireland, the cross is a fusion of traditional Celtic art and ecclesistical culture. It is similar in form to the 12th century Cross of Cong, the components of the Antrim cross in the Hunt Museum in Limerick, and a contemporary of the 8th-century Anglo-Saxon specimen, housed at Bischofshofen in Austria, as well as the bossed metal and wooden Dumfriesshire cross, whose fragments are in the National Museum of Scotland. An exquisite example of medieval goldsmithing, the Tully Lough Cross exemplifies the start of the tradition of Irish processional crosses that culminates in the Cross of Cong. It is now on display at the National Museum of Ireland in Kildare Street along with other masterpieces of Celtic metalwork, such as the Ardagh Chalice, the Tara Brooch, the Derrynaflan Chalice and the Moylough Belt Shrine. |

|

METALWORK OF THE

CELTS HISTORY OF CELTIC CULTURE |

|

DESIGNS OF THE ANCIENT

CELTS |

Where Was It Discovered? The Tully Lough Cross was found at the bottom of Tully Lough in County Roscommon, near a small crannóg, in July 1986. After an unlawful attempt to secure a sale of the artifact to the Getty Museum California, for a reputed $1.75 million, the cross - minus several components and in a state of disrepair - was eventually acquired by the National Museum of Ireland in 1990, who supervised its restoration. What Are the Characteristics of the Tully Lough Cross? The cross is composed of an oak upright and crosspiece, connected in the middle with a simple halving joint, supported by an iron nail. The construction is encased in plain sheets of tinned bronze, secured with tubular binding strips. The arms of the cross are cusped, while a number of cast and gilt raised bosses and flat mounts are attached at the front and back. The decoration is more elaborate on the front-facing panels than at the back. Three of these are ornamented with simple interlace designwork while two others depict a human figure sandwiched between two gaping beasts - possibly depicting Daniel in the Lions Den. The human images are very similar - both wear a kilt-like tunic that extends below the knees - but the eyes of the upper person are open while those of the lower figure are shut. As it happens, the human-figure-between-two-animals motif occurs in similar form on a 9th-century gilt silver bell shrine (origins unknown), currently part of the NMI collection, the Cavan brooch and the St-Germain shrine mounts, as well as later artifacts like St. Manchan’s shrine and the Cross of Cong. In addition, it also features on several high crosses including the South Cross at Ahenny in County Tipperary. This fact alone suggests that many of the high crosses of Ireland may have been modelled on metal crosses of earlier Christian-Celtic design. See also: History of Irish Art. What Sort of Designwork Appears on the Tully Lough Cross? Unlike the decorative scheme of the 12th century Cross of Cong, which derives from a Hiberno-Viking variant of the Urnes art style (see Viking Art), much of the decoration on the Tully Lough Cross originates from the La Tène idiom of late Iron Age Celtic culture. La Tene forms used include: pyramidal and circular bosses with "chip-carving" features such as egg and dart mouldings, pairs of eagles, spiral patterns terminating in birds heads or club motifs, and interlace patternwork, along with punched lentoids, and circular graphics. On the front of the cross, triskeles appear in a complex arrangement of interwoven S-scrolls and trumpet patterns. Many of these beautiful motifs derive from the traditional Celtic design repertoire, dating back to the Hallstatt culture. The same animal is represented on other items of contemporary metalwork such as the Cavan brooch and the St-Germain shrine mounts but it also occurs on later objects such as St. Manchan’s shrine and the Cross of Cong. The human figure between two beasts motif can be compared with a similar figure represented on an unprovenanced 9th-century gilt silver bell shrine in the National Museum collection (reg. no. 1920:37). It also occurs on stone high crosses such as the South Cross at Ahenny, Co. Tipperary, and part of the importance of the Tully Lough Cross lies in the fact that it demonstrates conclusively the long-held view that many of the Irish high crosses were modelled on metal crosses. other designs used on the cross can also been seen in a number of illuminated manuscripts, including the Cathach of St. Columba (early 7th century), the Book of Durrow (c.670), the Lindisfarne Gospels (c.698-700), the Echternach Gospels (c.700), the Lichfield Gospels (c.730) and the Book of Kells (c.800). The monumental scale of the Tully Lough Cross, allied to its ornate decoration, clearly indicates the likelihood that it was paraded on important religious feast-days and ceremonial occasions, a traditional useage that attained a highpoint during the 12th century. How it came to be disposed of in the lake is not known, although the looting proclivities of Vikings suggests its disposal may have been intentionally protective. |

|

• For more about Irish cultural history

and craftwork, see: Visual Arts in Ireland. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF IRISH GOLDSMITHERY AND METALWORK |