Celtic Culture

Characteristics of Celts Visual Art,

Language, Religion.

![]()

![]()

|

Celtic Culture |

|

EVOLUTION OF THE

ARTS |

Celtic Culture (c.1,000 BCE onwards)Contents • Introduction |

Muiredach's Cross (10th century CE) One of the famous Celtic High Crosses. |

When it comes to Celtic history, separating reality from myth is not easy. The origins, cultural traditions, and historical evolution of the European peoples we now call Celts are all highly obscure. We don't know precisely where Celts came from, nor how they integrated with the indigenous cultures they encountered. (Their relationship with the Scottish Picts, for instance, is quite obscure.) There appears to be no clear or continuous archeological record of Celtic migration or occupation, and little consensus between scholars concerning Celtic genetics and language. Like many tribal societies of prehistory, the ancient Celts had no tradition of written history. Instead, Celtic history, customs and laws were passed on from generation to generation by word of mouth: this, despite the existence of a respected intelligentsia caste of Druids, who were steeped in Celtic culture and heritage. |

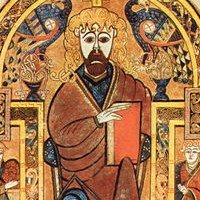

Christ in Majesty Detail From Book of Kells (c.800 BCE) One of the great masterpiece of Celtic design during the Hiberno-Saxon school of Insular art. |

|

HISTORY

OF CELTIC CULTURE ARTISTRY OF THE

CELTS |

As a result, much of what we know about the Celts derives from Roman historians of classical Antiquity - who typically portrayed all non-Romans as uncultured barbarians - or Celtic mythology (like the famous Irish Lebor Gabala Erenn: Book Of Invasions.) Fortunately, we do have one impartial witness, namely archeology, but as stated above the archeological record of prehistoric Celtic occupations is at present less than satisfactory. Thus, more investigation into Celtic prehistory is required before arriving at any firm conclusions about exactly where Celts originated, where they went, and how they affected the customs, arts and crafts of the local populations. With this in mind, here is a short guide to what we do know about Celtic history and culture. |

|

DESIGNS OF THE ANCIENT

CELTS |

|

|

The words "Celt" and "Celtic" originally came from Latin (celtus) and Greek (keltoi) and are used by historians to denote European peoples who spoke a Celtic language. Nowadays, the term "Celtic" is commonly used in connection with the languages and cultures of the "six Celtic nations", namely Brittany, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and the Isle of Man, where four Celtic languages are still in use: Breton, Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic, and Welsh. |

|

|

Historians sometimes classify Celtic peoples into "Continental Celts", denoting those on the continent of Europe, (eg. the Gauls) and "Insular Celts", meaning those of Britain, Ireland and other local islands. Celtic Origins

(c.1000-700 BCE): The true historical facts about Celtic origins were greatly obscured by the British 18th century antiquarian William Stukeley (1687-1765), who linked Celtic Druids with ancient monuments as Stonehenge and Avebury. In fact, these megaliths, as well as those at Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth, were built by Neolithic Man some two thousand years before the emergence of the Celt tribes who did not appear until about 1000 BCE, while Celtic culture - which coalesced into a distinguishable form no earlier than 850 BCE - was contemporaneous with militaristic Mycenean art and culture c.1650-1200 BCE - which the Celts absorbed as they passed through the Black Sea area - as well as Etruscan and Archaic Greek civilization. Celtic Settlers: Indo-European Tribes of Southern Russia The earliest Celts were a highly disparate but competitive group of Indo-European pagan tribes that began migrating into Europe from the steppes of southern Russia, the Kuban and the Crimea from about 1000 BCE onwards. It is possible that their culture owes something to the Urnfield culture which flourished in Europe between 1200 and 700 BCE, but the "early origin" view - held by a few historians - that the original ancient Celts can be traced back to the Bell Beaker culture of the third millennium BCE - while possessing the rather convenient merit of accounting for the wide dispersion of Celts and Celtic influence across Europe - lacks sufficient archeological support. According to the main archeological record, Celtic occupations can be traced no earlier than 1000 BCE. Celtic Hallstatt Culture (c.800-450 BCE) and The First Celtic Homeland Although the exact details of their progress are unclear, by 700 BCE Celts were firmly established astride the trading routes of the Upper Danube in central Europe. This view is confirmed by the Greek historian Herodotus, who refers to the Danube having "its source among the Celts near Pyrene", and also by archeological excavations in Austria. Indeed, the earliest discoveries of artifacts specifically associated with the Celts occurred near Hallstatt in Austria, which lends its name to the Celtic Hallstatt culture (c.800-450 BCE). Centred on a lucrative salt-mining industry, with its own widespread web of trading contacts, this early Celtic heartland also benefited from control of the trade routes along the Upper Danube waterways, which gave the Celts significant wealth as well as cultural contacts with much of Europe, including Etruria, and the Levantine. Trade also gave them an early knowledge of iron-smelting technology by which they secured a military edge over their rivals. They may even have had some prior expertise in iron, as the Maikop culture of the North Caucasus steppes has long been known for its early knowledge of metallurgy, notably bronze. On top of this, their use of iron ploughs enabled them to maximize agricultural production, while their skills in textile-making were also highly developed. Hallstatt art was primarily, though not exclusively, geometric in style, and was influenced by a combination of Caucasian, Etruscan and Upper Danubian designs. Westward Migrations During the Late Iron Age As the population within the Upper Danube Celtic heartland grew, Celts spread westwards across Europe in search of land for settlement, notably into Gaul, Spain, and Northern Italy. Spain was an especially attractive destination, being a mineral-rich country much appreciated by Phoenicians from Lebanon, Greeks and Carthaginians, and later also by Romans. This initial and relatively peaceful migration led to the introduction of Celtic language, commerce and culture as far as the shores of the Atlantic and the Western Mediterranean. Remaining active in trade, migrating Celts gravitated in particular to the main trading routes, such as the Rhine and Rhone rivers, as well as the principal trading settlements like Marseilles and Cadiz. Arrival of the Celts in Britain and Ireland Later, from roughly 450 BCE onwards, Celts also began arriving in Britain and Ireland, although the Greek geographer Pytheas (4th century BCE) referred to the British Isles as being "North of the land of the Celts", indicating that even as late as 350 BCE Britain was on the periphery of Celtic influence. Some Celtic tribes also spread eastwards into Asia Minor and along the Silk Road to Asia. Evidence suggests that, in addition to leaving their own mark on local cultures, Celts also absorbed a number of cultural elements from the indigenous peoples they encountered. The engravings at the Neolithic passage tomb at Newgrange Co Meath, Ireland for instance, include designs of lozenges, spirals, double spirals, concentric semi-circles, zigzags, and other symbols which Iron-Age Celtic craftsmen incorporated into their own styles. The same goes for designs found at other sites in the Boyne Valley like the Knowth megalithic tomb and the graves at Dowth. Celtic La Tene Culture (c.Early 5th Century - 1st Century BCE) By about 450 BCE, the Celtic heartland had expanded to include eastern France, Switzerland, Austria, southwest Germany, and areas of Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. It was during this period that a new Celtic culture, called La Tene after the type-site in Switzerland began to appear within the heartland. The La Tene style, characterized by geometric and zoomorphic designs, was influenced by Etruscan and Greek art, and emerged directly out of the preceding Hallstatt culture. Zenith of Celtic Power and Influence (400-250 BCE) Not long afterwards, (around 400 BCE) came a much larger "military" migration of Celtic tribes - including the Boii, Insubres, Lingones, and Senones - which swept down into Italy as far as Sicily, besieging Rome in the process. Other tribes invaded Greece and Asia Minor. Such was their success that even Alexander the Great was forced to conclude a non-aggression pact with them, before setting off on his conquest of Persia. The fourth century BCE was the highpoint of Celtic influence in Europe: their culture and language was an active force throughout the entire Continent, from the Black Sea to the Atlantic, and from the Baltic to the Mediterranean, while Celtic tribes controlled a number of important trading routes across Europe. By this time, the Celtic heartland may have moved from the Rhine river complex to the Rhone River in central and southern France - the only major river on the Continent that flows directly into the Mediterranean. In any event, during this period, almost every country of Western and Central Europe was influenced to a greater or lesser extent by Celtic culture, and Celts were regarded by the Etruscans, the early Romans and the Greeks as one of the four great peripheral nations of the known world. That said, the Celts would never have described themselves as a "nation". Although linked to some degree by a common language, similar pagan gods, expertise in iron, and similar forms of cultural expression, their communities were so extended across Europe, that there was no realistic possibility of cohesion or unity under any form of central authority. And they were as likely to fight each other as any outsider. This lack of unity would, in time to come, make them extremely vulnerable to the smaller but better organized military state of Rome. To give you an idea of the multiplicity of tribal societies which were associated with Celtic culture, here is a brief guide to the vast array of Celtic tribes and clans active in Iron Age Europe during the period 500-55 BCE, based on archeological excavations and written accounts by Greek/Roman historians. |

|

Tribes of Continental Celts In Central Europe, the original European centre of Celt activity from at least 1000 BCE, Celtic tribes included the Boii, who ranged across the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Germany and Austria; the Lugii in Poland; the Vindelici in Germany; the Cotini and Osiin Slovakia; the Eravisci in Hungary; and (from c.335 BCE onwards) the Scordisci, Latobici and Varciani in Slovenia and Croatia. By 500 BCE, Celts were established throughout the territory of "the Gauls", an area corresponding to modern day Belgium, France,and Switzerland, as well as parts of Northern Italy and Northern Spain. Gallic tribes with strong Celtic associations included: the Ambiani (Amiens), the Andecavi (Angers), the Aquitani (Bordeaux), the Atrebates (Arras), the Baiocasses (Bayeux), the Bellovaci (Beauvais), the Bituriges (Bourges), the Carnutes (Chartres), the Catalauni (Châlons), the Cenomani (Le Mans), the Helvetii (La Tène), the Lexovii (Lisieux), the Mediomatrici (Metz), the Medulli (Médoc), the Menapii (Cassel), the Morini (Boulogne), the Namnetes (Nantes), the Parisii (Paris), the Petrocorii (Périgueux), the Pictones (Poitiers), the Redones (Rennes), the Remii (Reims), the Senones (Sens), the Sequani (Besançon), the Suessiones (Soissons), the Tolosates (Toulouse), the Turones (Tours), the Unelli (Coutances), the Vangiones (Worms), the Veliocassi (Rouen), and the Veneti (Vannes). In Cisalpine Gaul (the north of Italy), Celtic occupations occurred from about 400 BCE onward until Roman control was asserted fully in 192 BCE, and involved tribes such as: the Graioceles, Salassi, Seguses, Taurini, and Vertamocorii in Piedmont; the Insubres, Orumbovii, and Cenomani in Lombardy; the Boii, Lingones and Senones in Emilia-Romagna. In the Iberian Peninsula - part of which was sometimes considered Gaul territory - Celts had been present since about 375 BCE, remaining independent until subdued by Rome in about 135 BCE. Spanish Celtic tribes included the Bracari, Callaici and Gallaeci in the north-west of the country; the Celtici and Lusitanians in Portugal; the Vacceani, Vettones and other Celtiberian clans in central Spain. Tribes of Insular Celts In England, Celtic tribes included: the Atrebates (Southern England), the Bibroci (Berkshire), the Brigantes (Northern England), the Cantiaci (Kent), the Carvetii (Cumberland), the Catuvellauni (Hertfordshire), the Corionototae (Northumberland), the Corieltauvi (Midlands), the Cornovii (Cornwall), the Dobunni (Severn valley), the Dumnonii (SW England), the Durotriges (Dorset), the Iceni (Queen Boudicea's tribe in East Anglia), the Parisii (Yorkshire), the Setantii (Lancashire), the Trinovantes (SE England), and the Uluti (Lancashire and Ulster). In Wales, the main Celtic tribes were the

Demetae (Dyfed), the Gangani (West Wales), the Ordovices (Gwynedd), and

the Silures (Gwent). The earliest Neolithic settlers in Ireland appear to have originated from Scotland, so these too might have been people of a more ancient quasi-Celtic culture. In any event, according to the Greek historian Ptolemy, Irish Celts included the Autini, Blanii, Cauci, Concani, Coriondi, Darini, Erdini, Gangani, Herpeditani, Iverni, Luceni, Menapii, Nagnatae, Robogdii, Udiae, Uterni, Vellabori, Vennicnii, Vodiae and Volunti tribes. Decline of the Celts in Europe (250-50 BCE) Returning to the wheel of history, if the period 400-250 BCE had seen the extension of Celtic power into almost every corner of Europe, the following two centuries witnessed a rapid decline of Celtic influence throughout the same area. In essence, Celts living east of the Rhine were forced to move west of the river by marauding German tribes like Cimbri and Teutoni. Meanwhile, Celts living in Northern Italy, Gaul and Iberia were gradually subdugated by the growing Roman Empire. By 50 BCE, the Celtic heartlands in Gaul were vanquished by Julius Caesar (the great Celtic tribal leader Vercingetorix surrendered in 52 BCE), and the remainder of Celtic Europe by the Roman Emperors Augustus and Tiberius. By 100 CE, only Celtic Ireland remained out of Rome's reach. Irish Celts: Survival and Renaissance During roughly four centuries of Pax Romana, Celtic craftwork on the Continent managed to combine with Roman art to form a Celtic-Roman art style. But overall, Celtic culture ceased to exist in an independent form except in the British Isles, particularly Ireland, while Celtic languages virtually disappeared on the Continent by about 450 CE. Fortunately for European civilization, and for early Christian art, the insular Celtic culture of Ireland remained largely intact. So, when the Roman Empire finally collapsed in the fifth century CE, triggering the anarchy and cultural stagnation of the Dark Ages (c.450-850 CE), Ireland was ready to play a critical role in European affairs. This came about when the country was effectively chosen by the Papal authority in Rome to be its principal outpost of Western Christianity while the pagan tribes from the East were pillaging the rest of continental Europe. In due course, thanks to the pioneering work of St Patrick and his followers, pagan gaelic Ireland transformed itself into the leading centre of Christian learning, and developed a unique monastic irish art which kept alive the traditions of classical scholarship until Europe recovered under King Charlemagne. From roughly 550 to 1000 CE, Celtic culture fused with Christian Biblical theology to produce a golden age of illuminated gospel manuscripts. The most renowned texts included the Cathach of St. Columba (early 7th century), the Book of Durrow (c.670), the Lindisfarne Gospels (c.698-700), the Echternach Gospels (c.700), the Lichfield Gospels (c.730) and the Book of Kells (c.800). See also: History of Illuminated Manuscripts (600-1200) and Making of Illuminated Manuscripts. Other types of medieval art practised in Ireland were monumental stonework, Celtic metalwork and high cross sculpture.

Celtic Language: History and Influence Although not as advanced in either pictographic or written languages as the regions around the Mediterranean basin and the Middle East, Neolithic Europe did develop a number of its own languages, such as Basque, Etruscan, Finnish and Hungarian. However, from 1000 BCE onwards, the wide-ranging Celts introduced their Indo-European language to a wide variety of peoples throughout the continent. As a result, the Celtic tongue was understood if not adopted as a common language of convenience: not unlike the English language is today. This alone was an important contribution to European culture of the day. There were two basic forms of the Celtic language: one version (now known as Q-Celtic, Goidelic, or Irish Gaelic), possibly originating in Neolithic times along the Atlantic regions of Western Europe, spoken in Ireland and the Isle of Man; and another version (known as P-Celtic, Brythonic or "Gaulish"), which was spoken in Gaul, England and Scotland until Roman times. (After the fall of Rome, the Irish introduced Q-Celtic into Scotland, where it superceded P-Celtic.) Celtic Language: Decline and Extinction As it was however, the Celtic tongue continued in general use for less than a millenium, and disappeared for two reasons. First, Celtic culture was oral rather than written. The Celts had no great tradition of a written language: indeed most were illiterate until the advent of Christianity with its introduction of written latin. Their use of the Celtic Ogham alphabet - comprising some twenty letters in shapes designed for easy carving on wood or stone - was confined solely to formal inscriptions (on tombstones etc.), of which perhaps 400 have survived, the great majority in Ireland. This reliance by the Celts on the spoken rather than the written word, proved fatal when Latin was introduced into Europe by Roman governors and administrators, and hastened the process of Romanisation. Second, Romanisation itself installed Latin as the new lingua franca, not least through Roman control of education, civil administration and trade. By the time Rome collapsed, the Celtic language had been extinguished as a living force on the European mainland, and survived only in Ireland and the Isle of Man, or among isolated Celts in Brittany, Scotland, Wales and Cornwall. Celtic Education: The Cultural Impact of the Druidic System In addition to a "warrior aristocracy", which functioned as their basic leadership cadre, Celtic tribes also had an intellectual elite of Druids, not unlike today's Orthodox Jews in Israel, or the Departments of Ideology under the old Communist systems of Eastern Europe. Celtic society was not theocratic, like today's Islamic states - nor was it even semi-theocratic, like Egypt - but it had a huge respect for learning (eg. science, mathematics, geography, astronomy, philosophy), for nature, and for religious ritual. All these matters were supervised and interpreted by the members of the Druidic caste. Moreover, as we have seen, there were no written sources, which meant that everything needed to be learned by rote, requiring even greater mental discipline. Much has been written about the sacrificial rites of these druids, and their importance to Celtic society, but it's possible that their enduring cultural contribution did not occur until Ireland converted to Christianity. For example, the monastic tradition of learning and scholarship, based on a severe regime of abstemious self-discipline and intellectual dedication, was the foundation for the great renaissance of Celtic art (c.550-1000 CE). Would this monastic regime have been embraced by the newly converted Celts as enthusiastically and successfully as it was, without the earlier tradition of Druidic learning? Another interesting parallel between the druids and the later Christian era in Ireland concerns their role as advisors. The Druidic system furnished tribal chieftains with advice on religion, law, finance and diplomacy; not unlike the Irish Christian monastic system provided advisors to royal courts across Europe from 800 to 1200 CE. |

|

Celtic Religion: Its Cultural Impact Historians have no clear picture of the unique features of the Celts' religious behaviour, nor its contribution to European habits of worship. Like many agricultural peoples (including the Romans) they worshipped gods and spirits associated with natural phenomena (sun, moon, thunder, lightning) and the annual cycle of nature, and these habits appear to have varied according to region: suggesting that Celts absorbed a good deal of local religious tradition. Moreover, judging by the astronomical alignment of megalithic structures such as Stonehenge, Newgrange et al, it seems that even the druids had little to teach earlier Neolithic Man about megalithic art or the cultural significance of religious or ceremonial structures. At any rate, there are no known religious buildings of Celtic antiquity to compare with Greek shrines or Roman temples, and as a consequence, no great tradition of religious art in the form of mural painting, figurative sculpture or decoration (mosaics). In the absence of any noteworthy architecture during the Celtic era, one can readily comprehend the awe inspired by the magnificent Romanesqe and Gothic cathedrals with their sculptures, stained glass windows and other decorative artworks, which emerged out of the Dark Ages 800-1100 CE. (For more, see: History and Styles of Architecture.) Two of the few religiously-inspired Celtic practices known in Ireland, were the offerings made to the gods in the form of weapons or other metalwork buried in the ground; and decorated pagan stone sculptures such as the Turoe Stone (Galway), Castlestrange Stone (Co Roscommon), Killycluggin Stone (Co Cavan), Mullaghmast Stone (Co Kildare) and Derrykeighan Stone (Co Antrim). Celtic Burials Although Celts had no need for temples, they did follow the custom of burying their chieftains and other leaders, complete with numerous weapons, ornaments, tools, drinking horns, pitchers, food bowls and other artifacts to assist them in the after-life. Indeed much of our knowledge about Celtic culture and art (eg. the Hallstatt and La Tene styles) stems from archeological discoveries made at these burial sites, especially from La Tene onwards when cremation was replaced by interral. Celtic Military Traditions: Their Cultural Impact The Celts had a formidable reputation as fighters, being noted for their use of body painting and face painting, as well as their excellent iron-made weaponry. In addition, their warrior caste took tremendous pride in their appearance in battle, which led to considerable expertise in Celtic metalwork - in the form of elaborately embellished swords, shields, helmets and trumpets. Personal ornaments of special recognition, not unlike modern military medals, were also crafted from gold, silver, bronze, electrum and other materials. This demand for high quality military and personal decorative metalwork, allied to the Celts general skills in blacksmithery (in the making of agricultural and equestrian items) and goldsmithing, not only resulted in Celtic Iron Age masterpieces like the Broighter Collar, the Petrie Crown and the Bronze trumpet from Loughnashade, it also laid the foundations for the great Christian metalwork of Ireland, as exemplified by the Ardagh Chalice, the Derrynaflan Chalice, the Moylough Belt Shrine, the Tully Lough Cross and the fabulous Cross of Cong as well as the secular Tara Brooch. Questions and Answers About Celtic Culture Q. What's the Difference Between Celtic and Neolithic Culture? Celts only appeared in Europe from 1000 BCE onwards. Any European activity before this date derives from earlier Neolithic styles such as the Urnfield (1200-750 BCE), Tumulus (1600-1200 BCE), Unetice (2300-1600 BCE) or Beaker (2800–1900 BCE) cultures. This applies especially to Ireland, where late Irish Stone Age and Irish Bronze Age art is often misattributed to Celts rather than their Neolithic ancestors. The truth is, a good part of Celtic art and design (notably spirals, lozenge and other abstract art) was absorbed from this earlier Irish heritage. Q. When Did Celtic Culture First Emerge? It appeared in Europe from 1000 BCE. Hallstatt styles emerged about 700 BCE, followed some two and half centuries later by the La Tene style. Q. Where Was Celtic Culture Established? The Celts settled and left their mark in large areas of central and western Europe, including Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Austria, southern Germany, Switzerland, northern Italy, France, the Low Countries, southern Germany, Spain, Britain and Ireland. Q. How Long Did Celtic Culture Survive? With some exceptions, the cultural traditions and languages of European Celts declined to almost nothing under the Roman Empire. Insular Celtic culture survived longer in Britain - particularly the remote parts of Wales, Cornwall and Scotland, although we still don't know the essential relationship or difference between Pictish and Celtic culture. In Ireland, one might say that Celtic culture has never been extinguished, although from Norman occupation times (c.1200) until 1650, Irish art as a whole remained dormant. In the 19th century, the discovery of ancient artifacts like the Petrie Crown, the Ardagh Chalice and the Tara Brooch, combined with a growing sense of national cultural identity, led to a Celtic Revival movement, led by William Butler Yeats, Lady Gregory, and "AE" Russell, which drew on Celtic literature, art and traditions. Today, one might say that this increased awareness of Celtic culture has become an integral part of Ireland's national identity - witness the expression "The Celtic Tiger". Q. What Are the Greatest Cultural Achievements of the Celts? The introduction of the iron plough and iron tools (including weapons), was a major contribution to European development. So too was Celtic Metalwork, (involving both Hallstatt and La Tene designs) which has rarely been exceeded in design or execution. Also, in a wider sense, Celtic cultural traditions helped to keep Iron Age Europe in touch with developments occurring in other parts of the known world, notably the Mediterranean basin, and thus contributed to the general cultural progress of the era. But in Ireland, the highpoint of Irish Celtic culture arose during the early Christian period, when the rest of Europe was plunged into the Dark Ages. Ireland's Celtic-Christian culture, exemplified by the glorious illustrated gospel texts, religious artifacts and free-standing cross sculptures, was crucial in keeping alive the flame of civilization. |

|

• For more about the history of Irish

culture, see: History of Irish Art. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF IRISH AND CELTIC ART |