Celtic Art

History, Characteristics, Designs: Hallstatt,

La Tene.

MAIN A-Z

INDEX - A-Z of IRISH ART

|

Celtic Art |

The Broighter Boat (1st century BCE) A gem of La Tene Goldsmithery (National Museum of Ireland) |

Broadly speaking, the earliest Celtic arts

and crafts appeared in Iron Age

Europe with the first migrations of Celts coming from the steppes of Southern

Russia, from about 1000 BCE onwards. Any European art, craftwork or architecture

before this date derives from earlier Bronze

Age societies of the Urnfield culture (1200-750 BCE), or the

Tumulus (1600-1200 BCE), Unetice (2300-1600 BCE) or Beaker

(2800–1900 BCE) cultures. |

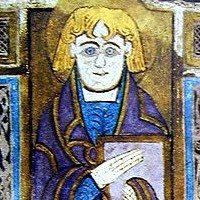

St John from the Book of Mulling (c.790) An illuminated gospel text with portraits bordered by interlaced animals and knotwork. Even St John's hair and clothing is interlaced. (Trinity College, Dublin) |

|

|

What Were the Early Influences on Celtic Art? The first Celts brought their own cultural styles, derived from the Caucasian Bronze Age, as well as a knowledge of Mediterranean and Etruscan styles, derived from maritime trading contacts through the Bosporus between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean basin. Settling in the area of the Upper Danube, the Celts duly absorbed motifs of the ancient Danubian tradition. They also brought with them a knowledge of iron-making, metalwork and jewellery art, possibly developed from the Bronze-making Maikop culture of the Russia Caucasus, or contacts with the Levant. (The later La Tene silver masterpiece, known as the "Gundestrup cauldron" is believed to have been made in the Black Sea region.) |

|

HISTORY OF CELTIC CULTURE ARTISTRY OF THE

CELTS |

|

DESIGNS OF THE ANCIENT

CELTS |

What Was the First Style of Celtic Art? The earliest true Celtic idiom in the area of arts and crafts was the Hallstatt culture. This derived from the type-site situated in Salzkammergat (a salt mine region), near the village of Halstaat in Austria, and lasted from roughly 800 to 475 BCE. Although centred around Austria, the Hallstatt culture spread across central Europe, divided into two zones: an eastern zone encompassing Slovakia, Western Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, Austria and the Czech Republic; and a western zone which included Southern Germany, Switzerland, Northern Italy, and Eastern France. The Hallstatt culture was founded on its lucrative European-wide trade in salt, and iron implements, and its prosperity was fully reflected in the burial sites of its chieftains and wealthy nobility, which contained huge quantities of finely crafted artifacts, jewellery, pottery, tools and other objects. |

|

|

What Were the Main Characteristics of Hallstatt Arts and Crafts? Hallstatt art from Central Europe is noted for its high quality iron tools and weaponry, along with its bronze-based manufacture of decorative items and ornamentation. But relatively few silver or Gold objects have been found from this era. Hallstatt was influenced by the militaristic Mycenean art and culture c.1650-1200 BCE which the Celts absorbed as they passed through the Black Sea area. The type-site in Austria, fully excavated by archeologists in the 19th century, included more than 2,000 graves packed with an assortment of functional and ornamental items. These and other Hallstatt-era hoards contained a mass of weaponry like axes, javelins, spears, cutting swords, daggers, helmets, bosses, shield plates. Choppers included the famous winged Hallstatt axe, while swords were long and heavy, and their hilts were crescent-shaped, with big pommels, or antennae, while shields were round. Several broad bronze belts were unearthed, decorated in repousse style with beast and geometric designs. Also found were numerous items of bronze and iron jewellery (brooches, ring ornaments, various types of amber and glass beads), many of the objects being decorated with animals and abstract geometrical patterns. Brooches were especially common and included both the primitive safety-pin type (Peschiera) and the Balkan/Greek spiral style (spectacle), as well as specimens in animal forms. Pottery was polychrome but unpainted. Among the more unusual discoveries was the body of a German chieftain, buried about 550 BCE in a silk cloak almost certainly woven in China. Although it evolved and was influenced in several ways during its 300-year lifespan, the Hallstatt art style is typically very geometric. Its advances over the preceding Urnfield culture are characterized more by technical rather than aesthetic improvements. If anything, there is a tendency toward the extravagant (akin to the Baroque), with a complete absence of later Greek Orientalizing influences. Hallstatt artists tended to break up smooth surfaces, and often employed colour contrast for effect. Motifs include bird shapes, probably from Italy, spirals, animal designs (zoomorphs), knotwork and fretwork, but few plant patterns. Figures frequently were set out in pairs, exemplifying a general concern with rigid symmetry. What Style of Celtic Art Came After Hallstatt? Archeologists call the next type of Celtic art style "La Tene", after the type-site located near the village of La Tène on the northern shore of Lake Neuchâtel, Switzerland. Discovered in 1857, the site was fully excavated by Swiss geologists and archeologists up until 1885. A total of over 2,500 objects were unearthed, mainly made from metal. Perhaps reflecting the militaristic nature of the La Tene era, most of the items were weapons, including more than 150 swords (mostly unused), nearly 300 spear-heads, and 22 shield plates. Other objects included nearly 400 brooches, as well as tools and other artifacts. The La Tene style spanned some 400 years between 500 and 100 BCE, and coincided with a westward shift in the continental Celtic heartland from the Upper Danube in Austria to the Upper Rhine around Switzerland and the River Rhone in France. La Tene represents the first highpoint or flourishing of Celtic art, demonstrating the prosperity and widening reach of Celtic culture. As it was, the La Tene era coincided with

the end of corpse cremation and the switch to inhumation, or burial. Much

to the benefit of archeology, this resulted in more burial sites, with

more hoards of personal possessions and household objects being interred

with the dead person to facilitate his enjoyment of the expected afterlife.

It is from these caches of artifacts that we derive our understanding

of this Celtic civilization

and culture. What Were the Main Characteristics of La Tene Arts and Crafts? The La Tene style, as revealed in numerous excavations across Europe - including Britain and Ireland - as well as in Greek and Roman texts, was a more mature type of Celtic art. According to Paul Jacobsthal in his seminal work "Early Celtic Art" (1944), the La Tene movement can be divided into four stages: The Early Style (c.480-350 BCE), The Waldalgesheim Style (c.350-290 BCE), The Plastic Style (290-190 BCE) and The Sword Style (190 BCE onwards). In general, La Tene artifacts of the Mediterranean areas of Celtic habitation, particularly France and Italy, exhibit a greater maturity and nobility of expression than the areas of central Europe, owing to their greater contact with the Graeco-Roman world. Noteworthy La Tene artworks include a wealth of goldsmithery, including stunning gold artifacts such as torcs and gold collars (eg. Broighter Collar from County Derry), bands, neck chains, clasps and bracelets, a limited amount of gold sculpture (eg. Broighter Boat), gold and silver cauldrons (eg. the Gundestrup Cauldron, found in a bog at Himmerland, Denmark), as well as a range of bronze items including shields (eg. the bronze Battersea shield, the Witham Shield from Lincoln), trumpets (eg. the bronze trumpet from Loughnashade, County Armagh), bowls, flagons and ornamental objects (eg. the later Petrie Crown from County Cork), many incised or engraved with typical La Tene patternwork. Iron artworks were also common, an interesting example being the wrought-iron firedogs (eg. from Capel Garmon, Gwynedd) to hold roasting spits or logs. La Tene patterns were influenced by formal motifs imported from Greece, Italy and the Caucasus, but central and western European Celtic metalworkers quickly evolved their own unique interpretations of abstract flowing patterns. The result a highly stylized form of curvilinear art, based mainly on vegetable and foliage motifs, such as leafy palmette forms, acanthus leaves, tendrils, vines and lotus flowers together with spirals, triskels, S-scrolls, and trumpet shapes. Other geometric decorations included wheeled cross motifs, zig-zags, cross-hatch, herring-bone, concentric circles and more. Among these abstract patterns, Celtic La Tene artists interwove a wide range of zoomorphic animal designs, featuring serpent heads, wild boar, owls and others. All these patterns, sometimes embossed with red or other enamels, appeared on the personal adornments and weaponry of the Celtic warrior aristocracy whose power and influence was to reach its zenith during the period 400-300 BCE. Are There Any Examples of La Tene Painting or Sculpture? Despite the obvious wealth of continental

Celts during the La Tene (and Hallstatt) period, there are no known examples

of paintings, only a relatively

small amount of sculpture, and few if any

noteworthy figurative carvings. All we have are some horned heads, Janus-heads,

along with a number of anthropomorphic and therianthropic figures in wood,

clay or metal. The only high quality stonework produced by Irish La Tene sculptors is the series of decorated pagan stones, such as the Turoe Stone (Co Galway), Castlestrange Stone (Co Roscommon), Killycluggin Stone (Co Cavan), Mullaghmast Stone (Co Kildare) and Derrykeighan Stone (Co Antrim). Yes, we know of many examples of Celtic pottery, but in general, ceramic ware was not an especially valued craft or artform - certainly nothing to compare with Greek pottery of the time, although ironically the latter was definitely appreciated by the Celts. What Happened to the History of Celtic Art After La Tene? During the late period of La Tene and its immediate aftermath, from roughly 200 BCE to 100 CE, the Roman legions vanquished all the independent Celtic tribes on the Continent, and absorbed them into the Roman administration of Europe. Britain too was subjugated and treated likewise, apart from certain remote regions in Scotland, Wales and Cornwall. Only Ireland managed to stay free of Roman control. During the next three centuries or so of this Romanisation, Celtic culture, language and crafts gradually declined, except in Ireland. Even here, there were fewer opportunities for artists and craftsmen to develop their skills. Thus, broadly speaking, Celtic art stagnated until the 5th century. It was in the fifth century that barbarian tribes finally overcame the Roman Empire - at least in the West. In 410, Visigoth tribes under Alaric sacked Rome, and 45 years later the city was overrun once more - this time by Vandals under Gaiseric. With the collapse of the Roman civil authority across Europe, the region was plunged into anarchy and chaos - a period known to historians as the Dark Ages. It would last until roughly 800 CE. Meantime, the Christian Church based in Italy determined to use barbarian-free Ireland as one of its outposts. It despatched St Patrick to convert the country to Christianity. This was to have profound consequences, not only for the people of Ireland but also for Celtic art. See also Celtic-Roman art. What Happened to Celtic Art in Ireland After the Fall of Rome? The coming of Christianity to Ireland led directly to a renaissance in Irish Celtic art. This took three forms: first, a regeneration of Celtic metalwork; second, the production - in association with Anglo Saxon and German expertise - of a series of glorious illuminated gospel manuscripts; thirdly, the creation of outstanding free standing sculptures - the so-called High Crosses of Ireland. In essence, unlike the earlier pagan period of Celtic history, during which weapons and jewellery tended to predominate, most of the great artifacts created in the early Christian period are connected with religious worship. Even so, the draughtsmen, metalworkers and sculptors of the Christian era continued to make extensive use of the spirals, knotwork, zoomorphs and many other designs of their pagan past. |

|

Was the Christian Celtic Renaissance Caused Solely by the Church? No, not completely. Because the country was spared the ravages of both the Romans and the barbarians, Irish Celtic culture continued to evolve. Between 300 and 400 CE Irish Celts developed a simplified Ogham alphabet in order to imitate Roman inscribed monumental sculpture. These new "Ogham Stones" served numerous functions: ancestral grave markers, memorials, and territorial borders, to name but a few. A notable example of such pre-Christian stones is the decorated pillar at Mullamast, County Kildare. (Note: there is no known written language in Ireland before Ogham: Celtic culture relied on oral rather than written traditions, leaving historians to separate myth from historical fact - see Lebor Gabala Erenn (Book Of Invasions). Metalwork also evolved. New techniques were introduced, including fine-line enamelling and ribbed-decoration, as well as enhanced versions of La Tene-style zoomorphic animal heads, curvilinear motifs and spirals. New forms included novel types of dress ornaments, notably the penannular brooch - a type of ring brooch with a gap through which a pin could be inserted - and the hand-pin - named after the shape of its head which resembled the palm of a hand. Some of these innovations were combined to great effect: for example, the zoomorphic penannular brooch was completely unique to Ireland, while later models were rendered even more exquisite by the use of multicoloured enamels and millefiori glass ornamentation. One of the great specimens of Celtic jewellery is the ring brooch known as the Tara Brooch (c.700). How Did the Church Help Irish Celtic Art? The great innovation of the Church in Ireland was the development of the monastery system - the establishment of a network of monasteries responsible to their founders like St Patrick, St Columba et al, rather than the regular episcopal hierarchy. This permitted greater freedom of action in both religious and aesthetic matters. In due course, these monasteries grew into renowned centres of learning - of spiritual and temporal subjects - while their scriptoriums and workshops, drawing on Celtic traditions, produced a range of early Christian art and developed unrivalled expertise in several applied arts and crafts. All this was facilitated by funds provided by the Church of Rome, who by the early seventh century, if not before, had assumed the role of patron of the arts in Ireland. It also introduced literacy into the country. See also Irish Monastic Art. How Did Christian Celtic Metalwork Develop? The evolution of early ecclesiastical metalwork in Ireland began in the 7th century with bronze reliquaries - that is, small hinged boxes containing the relics of Saints. In time, these reliquaries grew in size and ornamentation, later versions (eg. those of Bishop Conlaed and St Brigid) being adorned with precious metals. After reliquaries came new techniques, materials and colours - the result of metallurgical methods from overseas as well as local skills - including "chip-carving" (a method employed by German jewellers) whereby a smooth surface was converted into numerous angled planes to catch the light. Other fine techniques mastered by Celtic metalworkers included the use of gold filigree, multicoloured studs (eg. of enamel, millefiori, and amber), and stamped foils. A superb example of Celtic goldwork of this period (known incidentally as the Hiberno-Saxon school of Insular art) is the Moylough belt shrine. Another innovation of Celtic craftsmen was their method of creating a highly complex piece of (eg) bronzework out of a series of cast, hammered and spun sections put together on a (eg) a bronze core and pinned (instead of soldered) into place. The supreme exemplar of this technique is the silver Ardagh Chalice, built up from over 350 separate parts. Other religious masterpieces from Ireland include: the bronze Moylough Belt Shrine, the silver Derrynaflan Chalice and the two bronze-encased wooden processional crosses - the Tully Lough Cross and the famous Cross of Cong, constructed for King Turlough O'Connor in the 12th century. In their style of decoration, all these works of religious art remain quintessentially Celtic, dating back to ancient pagan traditions. How Did Illuminated

Manuscripts Develop? Like relics, illuminated gospel texts were used as precious objects of veneration, often only brought out on special feast days and festivals. If Celtic metalworkers in the monastery's workshop had to endure the extreme heat of furnaces and molten metal, the scribes, apprentice draughtsmen and master artists in the scriptorium suffered above all from the cold. Working all hours in freezing temperatures, they toiled for unknown hours to produce hand-made vellum, upon which was written word-by-word, line-by-line, page-by-page, the holy script. After this came the equally painstaking processes of illustration and illumination. Then came the stitching together of the pages, and finally, the covers. Then the Vikings would arrive destroy the manuscript and butcher the monks - well, not always, but it happened, and not that rarely. In any event, like the Ardagh and Derrynaflan chalices, the early Christian religious manuscripts remained essentially Celtic in design, being covered with incredibly complex patterns of traditional motifs, including the triskele, the trumpet, zoomorphic imagery, spirals, rhombuses, crosses, knot designs and countless other fantasy-filled graphic ornamentation and tracery - nearly all derived from the traditional designs of pagan Celtic metalwork. Among the most famous illuminated manuscripts are the Cathach of St. Columba (early 7th century), the Book of Durrow (c.670), the Lindisfarne Gospels (c.698-700), the Echternach Gospels (c.700), the Lichfield Gospels (c.730) and the Book of Kells (c.800) - especially its Chi/Rho Monogram Page with its fabulous decoration. They are among the greatest treasures of early Christian art of the Middle Ages, and perhaps the most famous works in the entire history of Irish art. They also had a significant influence on religious scriptoriums in contemporary Europe. The anti-classical styles of texts like the Book of Kells were carried to numerous monasteries and religious centres on the Continent where they influenced the development of Carolingian, Romanesque and Gothic art for the remainder of the Middle Ages. See also: History of Illuminated Manuscripts (600-1200) and Making of Illuminated Manuscripts. How and When Did Celtic High Cross Sculpture Develop in Ireland? The stone sculptures known as "High Crosses" were typically commissioned by local monasteries for religious sites, often replacing previously erected wooden structures. Their purpose varied from location to location: some commemorated an event, some were objects of veneration, others served as reference points. Still visible throughout Ireland, the majority were created during the period 750-1150, although the form attained its height in the early 10th century. They are classified into two basic types - those featuring relief scenes from the scriptures, or the lives of the Saints; and those featuring only abstract Celtic designs. The former would also have served to illustrate and explain important lessons from the Bible. In any event, these High Crosses are considered to represent the most important body of free-standing sculpture created between the Fall of Rome and the Florentine Renaissance, and are one of the great contributions to the history of visual arts in Ireland. Famous examples include Muiredach's Cross at Monasterboice, the Cross at Castledermot and the Ahenny High Cross. Was There a Continuous Tradition of Celtic Designwork in Ireland? Most definitely. One only has to compare the triple spirals, rhombus shapes, lozenges or concentric circles of the Newgrange megalithic tomb (built c.3300 BCE) (or the geometric imagery at the Knowth megalithic tomb) with the spiral ornamentation in the Book of Kells (written 4,000 years later), to appreciate the unbroken tradition of Celtic designwork. Some learned writers go to great pains to distinguish between "ancient" and "medieval" Celtic designs, but with the greatest respect, I can't agree. I think the answer to the question - What's the difference between ancient and medieval Celtic art - is: very little. Of course each era produces its singular innovations, but I think the most impressive thing about Celtic art (at least in Ireland, which has the greatest trove of Celtic artworks) is its continuity of creative design. See also: Celtic Revival. |

|

• For more about painters and sculptors

in Ireland, see: Irish Artists. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF IRISH AND CELTIC ART |