Icon Painting

Characteristics, History, Byzantine/Russian

Icon Painters.

MAIN A-Z INDEX - A-Z of PAINTING

|

Icon Painting |

|

WHAT IS ART? |

Icon ArtWhat Are Icons? Icons (from the Greek term for "likeness" or "image") are one of the oldest types of Christian art, originating in the tradition of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Typically they are small-scale devotional panel paintings, usually depicting Christ, the Virgin Mary or the Saints. Among believers of the Eastern Orthodox Church (eg. in Greece, Russia, Ukraine, Turkey), painted icons were seen in every home, and were also regarded as an essential decorative element of the Church, which accorded them special liturgical veneration. In fact, ever since the Byzantine Comnenian period (1081–1185) icons served as a medium of theological instruction via the iconostasis - the Orthodox screen of stone, wood or metal between the altar and the congregation - to which a large variety of icons would be attached, depicting pictorial scenes from the Bible. In fact, the interiors of Orthodox Churches were often entirely covered with this form of religious art. Closely identified with Byzantine art (c.450-1450) and, somewhat later, with Russian Art (c.900 onwards), Icons are still in use today, especially among Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Coptic Churches. |

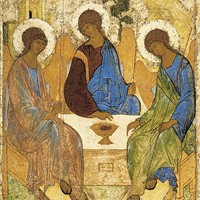

Holy Trinity Icon (c.1411) By Andrei Rublev, Theophanes' pupil. Tempera on wood panel Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. One of the greatest paintings ever. |

|

Characteristics of Icon Art Diverse Media Variety of Sizes Symbolic Art All this is like Egyptian art of Antiquity, in which (for instance) a person's size was calculated by reference to his/her social status, rather than by the rules of linear perspective. Medieval painting - like that of the Proto-Renaissance (c.1250-1350), and the International Gothic era (c.1375-1450), also employed a variety of symbols. Symbolic or not, Icon art was important because it gave the petitioner direct communication with the sacred figure represented. History of Icon Art Origins The origin of Icons can be dated to the era of early Christian art, when they served as paintings of martyrs and their feats, which began to be publicized after the Roman legalization of Christianity, in 313. In fact, within a century or so, only Biblical figures were permitted to be represented in icon form. (The Roman Emperor was deemed to be a religious figure.) The earliest portrayals of both Jesus and Mary were much more realistic than the later stylized versions. Thereafter, it took several centuries for a universal image of Christ to emerge. The two most common styles of portraiture included: a form depicting Jesus with short, wiry hair; and an alternative showing a bearded Jesus with hair parted in the middle. As Rome declined, the focus shifted to Constantinople, where Icons became one of the distinctive Byzantine types of art, along with mosaics and church architecture. See also: Christian Art, Byzantine Period. Iconoclasm Some 350 years later a dispute over their use (Iconoclasm) errupted during the 8th and 9th centuries. The Iconoclasts (those opposed to Icons) claimed they were idolatrous; supporters replied that icons were merely symbolic images. In 843 icon veneration was finally re-established, although very few early Byzantine icons survived the turmoil of the period - an important exception to this are the painted icons preserved in the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai, Egypt. Following the Iconoclastic controversy, more rules were introduced regulating iconic portrait art, as well as the character and scale of church fresco and mosaic decoration. Certain Biblical themes were especially promoted as subjects for these interior decorative arts, including Christ's Anastasis, and the Koimesis of the Virgin. Growth in Icon Painting Thereafter iconography flourished in particular during the period 850-1250, as part of Byzantine culture (only mosaics were more popular), and during the period 1050-1450 in Kiev, Novgorod and Moscow, where it became a major form of Russian medieval painting, being developed by artists like Theophanes the Greek, founder of the Novgorod school of icon painting. As far as the Byzantine icon painting tradition is concerned, we have only a few examples from the 11th century or earlier, and none preceding them. This is partly due to the Iconoclasm during which many were destroyed, and partly because of looting by Venetians during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, and lastly due to the sacking of the city by Ottoman Turks in 1453. From 1453 onwards, the Byzantine tradition of iconography was perpetuated in regions previously under the influence of its religion and culture - that is, Russia, the Caucasus, the Balkans and much of the Levantine region. To begin with, as a general rule, icon artists in these countries adhered strictly to traditional artistic models and formulas. But as time passed, some - in particular the Russians - gradually extended the idiom way beyond what had hitherto been accepted. During the mid-17th century, changes in ecclesiastical practice introduced by Patriarch Nikon led to a split in the Russian Orthodox Church. As a result, while the "Old Believers" continued to create icons in the traditional stylized manner, the State Church and others adopted a more modern approach to icon painting, by including elements of Western European realism, similar to that of Catholic religious art of the Baroque period. Icon Painters Sadly, the earliest icon painters remain anonymous, although some are known, including: Theophanes the Greek (1340-1410) who came to Russia from Constantinople and influenced the Moscow and Novgorod schools; Andrei Rublev (1370-1427), his collaborator Daniel Cherniy, and Dionysius (c.1440-1502) one of the first laymen to become an icon painter. Later Icon artists included Bogdan Saltanov (1626–1686), and Simon Ushakov (1626–1686) of the late Moscow school of painting, probably the last major icon-painter. Due to the popularity of icons among the Russians, a huge variety of schools and styles of icon painting developed, notably those of Yaroslavl, Vladimir-Suzdal, Pskov, Moscow and Novgorod. Famous Icons The most famous painting of Eastern Christendom is the 'Vladimirskaja', the 'Holy Virgin of Vladimir' (c.1131, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), supposed to have come from Constantinople to Kiev, and from there, in 1155, to Vladimir. On the 26 August, 1395, it was solemnly brought into Moscow amid the rejoicings of the people; on the same day the Mongols are said to have been repelled from the gates. There are many legends about this icon. When Napoleon entered Moscow it was rescued from the burning Kremlin and later restored in triumph to the cathedral. Thorough examination has revealed what is left of the original, after six over-paintings and renovations, spread over as many centuries. These remnants, though experts differ on points of detail, reveal the Virgin of Vladimir who, in expression and posture, has always been an archetype in Russian art. Next to the Virgin and Child, Saint George, the great martyr, is one of the most popular saints in Russian iconology. He is most often represented, not as the conquering hero, but as a solemnly enthroned Byzantine figure. All through the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which were the classic age of Russian painting, the Byzantine style remained the changeless expression of an unalterable faith, behind which all individual qualities disappeared. Other celebrated Icons include: St Peter (c.550, Monastery of St Catherine, Mount Sinai), St Michael (c.950-1000, Tesoro di San Marco, Venice), and Old Testament Trinity (1427, Tretyakov Gallery). One of the most venerated Byzantine icons (now lost) is known as The Virgin Hodegetria. According to Eudokia, the wife of Emperor Theodosius II (d.460), this wooden panel icon (housed in the Hodegon Monastery in Constantinople) was painted by Saint Luke. Copied widely throughout Byzantium, the image of The Virgin Hodegetria was enormously influential on Western depictions of the Virgin and Christ Child during the Middle Ages and Renaissance era. Collections Icon paintings and mosaics can be seen in a few of the best art museums around the world, including the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow; Museum of Art, Novgorod; the British Museum; the Victoria & Albert Museum; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and in situ at Hagia Sophia (Constantinople, now Istanbul); the monastic Church of Christ in Chora (Istanbul); Torcello Cathedral, Venice; Cefalu Cathedral, Sicily; Church of Our Saviour, Novgorod; and the Monastery of St Catherine, Mount Sinai, Egypt. Icon painting had a major impact on many Russian modern artists, notably Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962). For more modern treasures of Russian art, see Fabergé Easter Eggs, a series of beautiful but complex precious objects, made from gold, silver and gemstones by the St Petersburg House of Fabergé. |

|

|

|

• For more about encaustic and tempera

panel painting, see: Visual Arts Encyclopedia. Art

Glossary |