Francisco de Goya

Biography of Romantic Spanish History Painter,

Printmaker.

MAIN A-Z INDEX - A-Z of ARTISTS

|

Francisco de Goya |

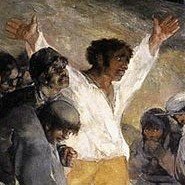

The Third of May 1808 (1814) Detail of central area. By Goya. Prado Museum, Madrid. |

Goya (1746-1828)Contents • Introduction NOTE: For analysis of works by Romantic

artists like Goya, |

|

WORLD'S BEST ART |

The Spanish artist Francisco de Goya is considered one of the key figures in Spanish painting and an important precursor of modern art. His portrait art, figurative drawing and printmaking documented important historical events in Spain during the late 18th and early 19th century. He is best known for his bold emotive paintings of violence especially those recording the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. His most notable works include The Nude Maja (c.1797), The Clothed Maja (c.1800), The Third of May 1808 (1814) and Saturn Devouring his Son (1819), all housed at the Prado Museum in Madrid. Other works include: Scene of the Inquisition (1800, Academia de S.Fernando); Portrait of Charles IV and His Family (1800 Prado); The Colossus (Giant) (1810, Prado); Portrait of the Duke of Wellington (1814, National Gallery, London). His dark Romanticism is illustrated by his Fantasy & Invention series (paintings, 1793), his Caprices (etchings, 1799), his Disasters of War (aquatints, 1812-15), and Black Paintings (14 murals, 1819-23). |

|

WORLD'S COSTLIEST ART |

|

WORLDS TOP ARTISTS |

Goya was born in 1746, in Zaragoza, a small village in Northern Spain. A few years late the family moved to Saragossa and his father gained employment as a gilder. At the age of about 14, Goya went to work as an apprentice to a local painter called Jose Luzan who taught him drawing and as was customary at the time, the young Goya spent hours copying prints of Old Masters. At the age of 17 Goya moved to Madrid and came under the influence of Venetian artist and printmaker Giambattista Tiepolo and painter Anton Raphael Mengs. In 1770, he moved to Rome where he won second prize in a fine art painting contest organized by the City of Parma. His first major commission came in 1774 to design 42 patterns which were to be used decorate the stone walls of El Escorial and the Palacio Real de El Pardo, the new residents of the Spanish Monarchy. This work brought him to the attention of the Spanish Monarchy which eventually resulted in him being appointed Painter to the King in 1786. Goya was a keen observer of humanity, and he was constantly making sketches of everyday life. However after contracting a fever in 1792 Goya was left permanently deaf by his illness. Isolated from people by his deafness, he retreated into his imagination and a new style started to evolve - more satirical, and close to caricature. There was growing macabre quality to his works which can be seen for example in his Fantasy and Invention series of thirteen paintings, 1793 - a dramatic nightmarish fantasy with lunatics in a courtyard. While he completed these series of paintings, Goya himself was convalescing from a nervous breakdown. |

|

|

|

|

In 1799, he brought out a series of 80 etchings entitled Los Caprichos (Caprices) commenting on a range of human behaviours in the manner of William Hogarth. In 1812-15, following the Napoleonic War, he produced a series of aquatint prints called The Disasters of War depicting shocking, horrific scenes from the battlefield. The prints remained unpublished until 1863. Compare Goya's realist portrayal of the war with the more romantic depiction of Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835). In 1814, to commemorate the Spanish insurrection against French troops at the Puerta del Sol, Madrid, Goya produced one of his greatest masterpieces - The Third of May, 1808 (1814, Prado, Madrid), which is acknowledged as one of the first true paintings of modern art. After 1815 Goya virtually retired from public life, and became increasingly withdrawn and more expressive in his works which echoed El Greco many years before him. Another set of pictures, his fourteen large murals known as the Black Paintings (1819-23), including Saturn Devouring One of His Children (1821, Prado, Madrid), reveal an extraordinary world of black fantasy and imagination. His works span a period of more than 60 years, and as time went on he became more critical of the world. He became bitter and disillusioned with society as the world around him changed, and he expressed these emotions through his art. In 1824, after much political upheaval in Spain, Goya decided to go into exile in France. He continued to work there until his death in 1828, at the age of 82. Towards the end of his life he became more reclusive, slipping deeper into madness and fantasy. Goya's role in the history of art is not limited simply to his supreme portraiture. In addition to his mastery of printing, his dramatic painting style influenced a great deal of nineteenth century French art and his works became the precursor to the Expressionist movement and an important forerunner of modern art. Along with Velazquez and Picasso, he is considered to be one of the three finest artists of Spain. |

|

|

Francisco Jose Goya: His Life and Art Two Spanish Virtuosi: Goya Versus Velazquez Prior to the Modernist era, Spain produced two supreme artists - Velasquez the Serene and Goya the Turbulent. Alike in their genius, they were unlike in everything else. Velasquez was a smiling spectator in the tragicomedy of life. Goya was a boisterous actor. Velasquez, the philosopher, shook his head indulgently and said, "What fools these mortals be." Goya, the fighter, brandished his fist threateningly and cried, "What rascals these mortals be!" And he himself was not the least of the rascals. Both Velasquez and Goya were Spanish to the core. But the spirit of Velasquez' painting was primarily national, while the spirit of Goya's painting was at all times universal. Velasquez was a citizen of Spain. Goya was a man of the world. Velasquez depicted the life of his compatriots. Goya represented the life of mankind. Goya was one of the most comprehensive of the world's painters. He may well be called the Shakespeare of the brush. His imagination was all embracing. The scope of his genius included portraiture, landscape painting, mythological painting, realistic stories, symbolical representations, tragedy, comedy, satire, farce, men, gods, devils, witches, the seen and the unseen and as was the case with Shakespeare's extravagant genius - an occasional excursion into the obscene. Physically, this roisterous knight of the dagger and the brush was impressive rather than handsome. Somewhat below the medium height, he had the figure of an athlete. His features were coarse and irregular, but they were alive with the fire of an unsuppressed impetuosity. His deep black eyes would suddenly light up with the impudence of a child about to play a naughty prank. His nose was thick, fleshy, sensuous. His lips were firm, aggressive and unabashed. Yet there lurked about their corners at times a smile of good-natured joviality. His chin was the round, sensitive, smooth chin of a lover. A lover of life, of gaiety, of beauty. He enjoyed three things with equal gusto - to flirt with a wench, to fight a duel and to paint a picture. He was a master in the art of indiscriminate living - an audacious, brawling, philandering, befriending, swashbuckling and dreaming Don Juan of Saragossa! Early Years One day, in 1760, a monk was walking slowly

over this road and reciting his breviary. A shadow lay across his path.

Looking up, he saw a young lad making charcoal

drawings upon the wall of a barn. Being somewhat of a connoisseur,

the monk stopped to examine the boy's work. He was amazed at the youngster's

aptitude. "Take me home to your parents," he said. "I want

to speak to them." Goya the Wild Young Man Arrives in Spanish Capital Here his reputation as an artist had preceded

him. Bayeu, who had arrived in Madrid shortly before him, introduced him

to the German, Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-79), the Superintendent

of Fine Arts in Madrid. Mengs, a somewhat better than mediocre painter

but somewhat worse than mediocre teacher, was at that time decorating

the royal palace at Madrid. From all the pupils who assisted him in this

work he exacted a slavish obedience and a faithful imitation of his own

unimpressive ideas. He offered to take Goya into his studio as one of

his assistants. Goya, whose artistic ideas were superior to those of Mengs,

refused the offer. |

|

|

Leaves Spain For Italy This time Goya set sail for Italy. Here

too, as in Madrid, he apprenticed himself to the study of the great masters

of the Renaissance and Mannerism,

including the short-live Caravaggio (1571-1610).

He applauded the geometric precision of their design, he extolled the

subtlety of their chiaroscuro,

the dramatic quality of Caravaggism.

He admired the accuracy of their observation, he worshipped the fire of

their genius - and he refused to be influenced by any of them. For the

greater part of his life his inspiration came from within rather than

from without. He was the product of no school. His art was strictly and

completely his own. Returns to Spain Chastened, at least temporarily, Goya abandoned his impossible quest and returned to Madrid. Here his earlier escapade had been fortunately forgotten. Once more he met his old friend Bayeu, found that he loved Bayeu's sister, married her and settled down. His student days were over. It was now necessary for him to think of making a living. Again Mengs offered him a job. This time Goya accepted the offer. Having agreed to follow the instructions of his German employer, he took that artist's lifeless mythological figures and breathed into them the spirit of living men and women. Thus far Goya had done nothing to prove his rank among the genuine artists of the world. He had been regarded merely as a playboy with a clever brush. Now, however, he revealed himself to a dazzled public as an inspired playboy. His riotous imagination, his daring design, his interplay of colour effect, his humour and his unerring instinct for the dramatic aroused the enthusiasm even of so hidebound a traditionalist as Mengs himself. As for the connoisseurs of Madrid who had been vainly seeking for signs of a new life in their national art, they greeted Goya's work with a veritable ovation. Goya accepted this public recognition of his genius with the same self-assurance with which he had accepted the smiles of his senoritas. Goya never suffered from excessive modesty - or, for that matter, from excessive vanity. He was merely conscious of a superior power within himself. "He knew now (at the age of thirty)," writes M. Charles Yriarte, "that he had only to take his brush in hand in order to become a great painter." Goya the Genre Painter Goya the Etcher Goya the Portraitist Having proved his mastery of the genre painting and the etching and his ability to arouse the enthusiasm of his public with his religious pictures, Goya now turned his hand to another branch of art - portraiture. Here he was successful from the start. To be painted by Goya became the fashion - indeed, the passion - of the day. Now one of Spain's most famous painters, his studio was besieged from morning till night by wealthy and noble clients. This was all the more surprising because he never flattered any of his subjects. He painted them as they were, in all their physical imperfection and with all their moral shortcomings. "Here we are," they seem to say to the spectator, "a bunch of as arrant rascals as you'd ever like to see." This is especially evident in the two portraits of Maja, subject unknown but believed to have been the Duchess of Alba, and in the portrait of King Charles IV and His Family. Maja Portraits |

|

|

Royal Portrait Realist Painter of Spanish Society He depicted the restless life of the city in The Blind Street Singer, The Pottery Market, The Vegetable Woman, The Runners on Stilts, The Carnival, The May Festival in Madrid, The Madhouse and The Bullfight. He immortalized the toils and the joys of the countryfolk in The Washerwomen at the Pool, The Harvesting of the Hay, The Attack on the Stagecoach, The Widow at the Well, The Village Wedding, The Water Carriers, The Country Dance, The Greased Pole and The Seasons. He pictured the horrors of war - for in spite of his turbulent spirit he hated the organized business of slaughter - in a series of devastating satires such as The Massacre of 1808, Forever the Same Savagery, The Beds of Death, The Hanging, The Garrote (a Spanish mode of strangling with an iron collar and a screw), Dead Men Tell No Tales, I Have Seen the Horrors and There Is No One to Help Them. Stark, honest, realistic, heart-gripping, these painted indictments of man's inhumanity to man. But most characteristic, perhaps, of all the pictures of Goya are his famous Caprices. Goya's Caprices Still another Caprice, entitled The Rise and the Fall, portrays the helplessness of Man in the hands of his Fate. A gigantic figure, with the legs of a goat and the face of a devil, has just taken hold of a man by the ankles and swung him aloft toward the sky. The man rejoices in his great good fortune and in his costly robes. There are flames spurting upward from his hands and his head. He is a king among his fellow men! In his ecstatic glee he fails to notice, poor little mortal, that other men, like himself, have just been raised aloft only to be dashed headlong to the ground. This pessimistic Caprice bears the following comment: "Destiny is cruel to those who woo it. The labour that it costs to rise to the top goes up in smoke. We rise only to fall." And so on. The Caprices of Goya are like an Inferno of Dante. But, unlike Dante, Goya depicts not the sufferings of the dead but the tortures of the living. And it would seem that Goya considered the Inferno of life to be even more tragic than the Inferno of death. Last Days in France On the sixteenth of April he passed on to his final journey. He was buried quietly at Bordeaux. It was not until 1900 that the remains of the exiled First Painter of Spain were brought back to Madrid. He was given a splendid funeral at last. His casket was drawn by eight horses adorned with gilt plumes as the entire population of Madrid looked on. Too bad that Goya wasn't alive to paint this last of the Caprices of his cynical destiny. It might have been the greatest of his masterpieces. Works by Goya can be seen in the best art museums across the work, especially in the Prado Museum in Madrid. |

|

• For a chronology of important dates

in the evolution of the visual arts, see: Timeline

- History of Art. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF OLD MASTER PAINTERS |