Mannerism

Definition, History, Characteristics of

Mannerist Art.

MAIN A-Z INDEX - A-Z of ART MOVEMENTS

|

Mannerism |

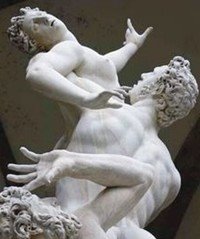

The Rape of the Sabine Women (1583) by Giambologna (Detail) |

Mannerism Style of Art (c.1520-1600)Contents • What is Mannerism? Further Resources • Cinquecento |

Wedding Feast at Cana (1563) (detail) Louvre, Paris. By Paolo Veronese. See also: Feast in the House of Levi (1573, Venice Academy Gallery). |

|

PAINT-PIGMENTS,

COLOURS, HUES WORLD'S GREATEST ART RENAISSANCE: NORTH

EUROPE |

In fine art, the term "Mannerism" (derived from the Italian word 'maniera' meaning style or stylishness) refers to a style of painting, sculpture and (to a lesser extent) architecture, that emerged in Rome and Florence between 1510 and 1520, during the later years of the High Renaissance. Mannerism acts as a bridge between the idealized style of Renaissance art and the dramatic theatricality of the Baroque. Mannerist Painting - Characteristics There are two detectable strains of Mannerist painting: Early Mannerism (c.1520-35) is known for its "anti-classical", or "anti-Renaissance" style, which then developed into High Mannerism (c.1535-1580), a more intricate, inward-looking and intellectual style, designed to appeal to more sophisticated patrons. As a whole, Mannerist painting tends to be more artificial and less naturalistic than Renaissance painting. This exaggerated idiom is typically associated with attributes such as emotionalism, elongated human figures, strained poses, unusual effects of scale, lighting or perspective, vivid often garish colours. Among the finest Mannerist Artists were: Michelangelo (1475-1564) noted for his Sistine Chapel frescoes such as The Last Judgement (1536-41); Correggio (1489-1534) known for his sentimental narrative paintings and the first to portray light radiating from the child Christ; Andrea del Sarto's two pupils Jacopo da Pontormo (1494-1556) and Rosso Fiorentino (1494-1540); Parmigianino (1503-40) the influential master draftsman and portraitist from Parma; Agnolo Bronzino (1503-72), noted for his allegorical masterpiece known as An Allegory with Venus and Cupid (1540-50) National Gallery, London; Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) a second rank painter but fine writer of works like Lives of the Artists (1550), as well as an architect who designed the Uffizi art gallery in Florence; the Venetian Jacopo Bassano (1515-92), Tintoretto (1518-94) one of the great drawing experts and a prolific composer of large religious paintings executed in the grand manner verging on the Baroque - see for instance The Crucifixion (1565); Federico Barocci (1526-1612) the pious religious painter active in Urbino and central Italy; Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527-93) known for his bizarre fruit and vegetable portraits; Paolo Veronese (1528-88) the Venetian colourist; Domenikos Theotocopoulos, known as El Greco (1541-1614) the Venice-trained Greek artist who worked in Spain, known for his highly individualistic style of art reflecting his vision of Christianity and worldly meaning; Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), also from Bologna, noted for his historical Farnese Gallery frescoes (1597-1608); and Adam Elsheimer (1578-1610), whose exquisite landscapes and nocturnal scenes - poised between tenebrism and chiaroscuro - influenced the likes of Claude Lorrain, Rubens and Rembrandt. For developments in Venice, see Venetian Altarpieces (1500-1600) and Venetian Portrait Painting (1400-1600).

Mannerist sculpture was more expressive than its Renaissance predecessor, and is exemplified by sculptors such as Giambologna (1529-1608), Benvenuto Cellini (1500-71), Alonso Berruguete (c.1486-1561), Juan de Juni (1507-1577), and Francesco Primaticcio (1504-1570), Jean Goujon (c.1510-68), Germain Pilon (1529-1590), Barthelemy Prieur (1536-1611) and Adriaen de Vries (1560-1626). In Italy, Mannerism declined from about 1590 onwards, coinciding with the arrival of a new generation of Italian artists, led by Caravaggio (1571-1610), who reinstituted the value of naturalism. Outside Italy, however, Mannerism survived as a form of courtly art well into the 17th century. In Britain it continued as Elizabethan, then Jacobean, court painting, while in France, it continued as the Henry II style at the royal court at Fontainebleau, under first Francis I (1515-47) - for details see Fontainebleau School (c.1528-1610) - and later Henry IV (1589-1610). The Hapsburg Emperor Rudolf II, based in Prague, was another important patron of Mannerism. For more than two centuries (c.1650-1900) Mannerist art fell into disfavour, but during the first half of the 20th century art critics began to take a more positive view, appreciating the modernity of artists like El Greco.

The Origins and Development of Mannerism Religious Turmoil If the harmonious and idealistic representations of the High Renaissance expressed the supreme confidence of man, who saw himself as the measure of all things in the first few decades of the 16th century, this certainty was soon shattered. In 1517, with his Wittenberg Theses, Martin Luther declared the religious war of the Reformation against the Catholic Church. For the Protestants, the papacy had become the epitome of universal moral and religious decadence. The chief bone of contention was the sale of so-called 'indulgences', with which the faithful could buy forgiveness from the Pope. The money from this lucrative business flowed into the magnificent new building of St Peter's Basilica in Rome. The rapid growth of the Reformation movement demonstrated the need for fundamental reforms within the Church. But there was a high price to be paid for it. Bloody wars were waged throughout Europe in the name of faith for over 100 years. The unity of the church broke down, its authority was increasingly called into question. Man No Longer the Centre of the Universe The insecurity that this produced was intensified by the most recent scientific discoveries, which put the world out of joint in the truest sense of the word. Copernicus had established that the sun rather than the earth was the still centre of the universe, around which all the stars and planets, including the earth, revolve. This heliocentric view of the world entirely contradicted the Church's view of itself, and its claims to domination, since the idea that the representative of God did not sit at the centre of cosmic events was far from attractive. In addition, the spectacular circumnavigation of the world by Ferdinand de Magellan and Christopher Columbus' discovery of America bore out the suspicion that the earth was round not flat, nor was central Europe the centre of the world. Mannerism Reflects the New Uncertainty The Copernican change in the conception of the world is reflected in the Italian art of the period. Painters - like many of their contemporaries - lost their faith in ordered harmony. They were of the view that the rational laws of art based on equilibrium, were no longer sufficient to illustrate a world that had been torn from its axes. To this extent, the art of this period Mannerism - is the art of a world undergoing radical change, impelled by the quest for a new pictorial language. Mannerism reflects the new uncertainty. Reaction Against the Perfection of the Renaissance The young generation of artists sensed that they could not develop the style perfected by Old Masters like Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael any further. These great masters had succeeded in painting pictures which looked entirely natural and realistic, while at the same time being perfectly composed in every detail. In their eyes, the painters had achieved everything that could be striven for according to the prevailing rules of art. For this reason the Mannerists sought new goals, and - like many of the avant-garde artists of Modernism hundreds of years later - they turned against the traditional artistic canon, distorting the formal repertoire of the new classical pictorial language. Even the great Michelangelo himself turned to Mannerism, notably in the vestibule to the Laurentian Library, in the figures on his Medici tombs, and especially in his Last Judgment fresco painting in the Sistine Chapel. Jacopo Pontormo Jacopo Pontormo combined the influences of his teachers Andrea del Sarto and Leonardo with impulses from Raphael's late work, as well as the painting of Michelangelo, arriving at a pictorial language which, for all its realism, still seems other-worldly. In his painting The Visitation of Mary (1528-30, S. Michele, Carmignano), showing the encounter between Mary and Elisabeth, the women seem like supernatural beings. They barely touch the floor. Their bodies are lost in the voluptuous folds of their metallically gleaming drapery. They stand in the air like flickering flames. The eye trained in Renaissance painting was taught that there are other ways of seeing beyond the purely naturalistic. More than any artists before them, Mannerist painters stressed the individual way of painting, the personal vision and pictorial understanding of things. They discovered the symbolic content of visual structure, the expressive element of painting. They consistently resisted equilibrium. So the circular and pyramidal compositions typical of the Renaissance disappeared. Classical compositional patterns were unbalanced by surprising asymmetrical effects. Painters abandoned the basic structural model that stabilized the painting. Thus, for instance, the pictorial structure - based upon central perspective, focusing the viewer's gaze on a single point - is now replaced by a dynamized pictorial space of undefined depth.

Parmigianino In Parmigianino's painting of the Madonna dal Colla Lungo (1535, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) the immediate foreground and the distant background appear without transition, almost fragmentarily juxtaposed. The pictorial weights are unevenly distributed. On the left hand side of the picture, the painter places a cramped band of angels, while spatial depth opens up on the right-hand side, its only focus being a brightly-lit row of columns, behind which there stretches a broad, dark landscape. And yet the painting does not break down into two parts. The painter uses overlaps (the Madonna's artificially billowing cloak restrains the vanishing gaze into the depths) and witty formal analogies to hold the painting together. Thus, for example, he produces a compositional reference between the column in the background, Mary's gleaming knee and the extended leg of the angel in the foreground. Slender, elongated limbs, splayed, twisting and turning bodies, contradicting all the traditional laws of proportion, are a characteristic of Mannerism. Parmigianino - of the Parma School of painting (1520-50) - was another painter who gave his Madonna unusually long limbs. Particularly striking is the gracefully curved, swanlike neck, which gave the painting the title Madonna dal Colla Lungo, or The Madonna with the Long Neck (1535, Uffizi). The painter intensified the idealized features of Raphael's organic figure drawing into a stylised elegance, which contemporaries admired for its grace. This confident and exaggerated artificiality, its contrivance, its structures, gave Mannerism, or 'manierismo', its name. In the 17th century, however, the concept received the negative connotations that attach to it even today. From now on it was associated with a learned, rigidly formulaic quality beyond all study of nature. But in the 16th century this style enjoyed great popularity at the courts of Europe, particularly that of Francois I, who had his castle at Fontainebleau, near Paris, decorated by a group of Italian, Flemish and French artists (1530-1560). The magnificent decorative style of the Fontainebleau school which, as the painting Gabrielle d'Estrees and her Sister in the Bath shows, was not without frivolity and a degree of raciness, but had little in common with Italian Mannerism, whose principles return a hundred years later in French Rococo. The Mannerist Reality The Mannerists took the illusionistic picture space, with its imitation of reality, and transformed it into an 'intellectual' picture space, showing what was really invisible and accessible only to the inner eye. Modern art has its roots in this approach, in which the artist's individual vision and view of things becomes the sole yardstick. Small wonder, then, that a painter like El Greco, one of the great masters of Mannerism, was discovered by artists at the beginning of the 20th century as a key forerunner of modern art. El Greco and Tintoretto Domenikos Theotocopoulos, who was only ever referred to as El Greco at the Spanish court where he spent most of his working his life is - along with Tintoretto from the school of Venetian painting - one of the most important painters of the second half of the 16th century. Both painters wanted, like Parmigianino, to create something new. But their paintings were not a refined game with new artistic media; rather, above all they wanted to show intellectual content in their religious art, which would reveal the invisible. Tintoretto also admired the Renaissance masters, particularly Michelangelo and Titian. By his own account, he aimed to "unite the drawing of Michelangelo with the colour of Titian", in order to reveal the impossible, the transcendent which could not be represented. He sought a pictorial language which made it possible to sense the spiritual content, the divine. Please see, for instance: The Disrobing of Christ (1577), The Burial of Count Orgaz (1586-88), View of Toledo (1595-1600), Christ driving the Traders from the Temple (1600), Portrait of a Cardinal (1600), and Portrait of Felix Hortensio Paravicino (c.1605). The reality oriented Renaissance painters, who so casually introduced mythological figures and Christian saints into this world, proved unhelpful in this regard. The Mannerists' goal had explicitly not been to create a deceptively real picture space which the viewer imagined he could enter at any time; their aim, rather, was to create paintings which were not a depiction of this world. As there is no way of visualizing such a supernatural world, the painters were thrown back on the imagination. They staged their stories like theatre-directors. Using unreal, stage-like lighting with dramatic effects of light and dark, and with highly independent perspectives or daring foreshortening, they tried to distance their pictures from real life. They transformed religious scenes into enthralling scenarios. A comparison of the Last Suppers of Leonardo and Tintoretto clearly shows the difference in vision and approach: in contrast to Leonardo's balanced, symmetrical frontal composition, Tintoretto's pictorial space is given a dynamic quality by the table placed diagonally to the picture surface. In Leonardo's painting Christ was what the Christian faith said he was: quite human and quite divine at the same time. In Tintoretto's work this peaceful coexistence falls apart again. There is a clear difference between the bustle of the world in the foreground, where the servants are busily fetching food and drink, and the theological story in the depth of the painting. These two levels are given unity only by the lighting and the ecstatic vitality of the pictorial structure as a whole, which is lent compositional equilibrium by a barely visible band of angels swirling above the whole scene. See also the dramatic effects of chiaroscuro and Caravaggism, perfected by the iconoclastic Baroque painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), in works like The Calling of St Matthew (1599-1600), The Martyrdom of St Matthew (1599), Conversion on the Way to Damascus (1601), Supper at Emmaus (1602), The Death of the Virgin (1602, Louvre, Paris) and The Entombment of Christ (1601-3). Mannerist Illusionistic Painting Leads Into the Baroque A suggestive style of painting - in which real and unreal, the spiritual world and the perceptible world, can no longer be distinguished - was utterly alien to the painters of the Renaissance. In the Baroque, from about 1600, the intellectual pictorial worlds, created by the Mannerists as early as the 16th century, reach their apogee. The painters of the Baroque either leave earthly reality behind, or create a confusing interplay of illusion and reality. The compelling effect of this kind of illusionistic painting as made possible by the perfect mastery of linear and aerial perspective was recognized above all by the Church Fathers. In the face of the rumblings of the Reformation in the north, which were growing menacingly loud, compelling illusionistic painting struck the Catholic Church as a particularly appropriate way of making faith attractive. In 1562, at the Council of Trent, which heralded the 'Counter-Reformation' in the Catholic countries, it was decided that the mystical and supernatural sides of religious experience would henceforward be given prominence. Baroque art duly obliged. See for example: Classicism and Naturalism in Italian 17th Century Painting.

|

|

• For other art movements and periods,

see: History of Art. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ART HISTORY |