|

|

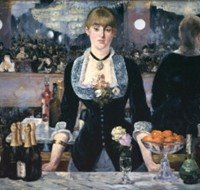

This shows the exceptional relationship

of Manet in relation to his painter friends and explains their worship

of him, the reverence which they show towards him and, on his part, the

reserve for which he is sometimes reproached, for instance, when he remains

aloof from their exhibitions. He has a unique and indomitable physical

bearing despite his retiring nature. This manner is independent of his

painting activity; it rejects all theoretical activity and is only the

result of a form, a style of living, an elegance, a dandyism (recalling

Baudelaire), an urbaneness and a taste for debate not without extreme

susceptibility (he duelled furiously one day with his friend Duranty when

he thought he found some reservations in the latter's mind). He always

had a great curiosity, sometimes a sudden weariness. Mallarme was to write

later, trying to recall to mind a characteristic trait of the friend who

was no longer there. Manet also had a great simplicity, even naivety.

Mallarme referred to his" ingenuousness". He rejoiced at being

admitted to the Salon and wanted nothing else, just as Baudelaire thought

twice as strongly of canvassing his election to the French Academy. Neither

wanted to be the cause of a scandal and yet, as Georges Bataille quite

correctly writes, Manet was to become the chance instrument of metamorphosis.

Why the scandal and why Manet? Up until then his career showed every sign

of brilliance and facility. He has been known since he was at the Couture

studio: in 1861, the portrait of his parents, in a rather Dutch form,

is accepted with honourable mention. Later his liking for Spain, shared

since Romanticism by so many artists and

writers, has nothing surprising about it. He still reveres the model,

even if he treats it in an unusual manner.

The blow falls with the exhibition of "Music

in the Tuileries" surrounded by Spanish paintings, at the Martinet

Gallery in March and April of 1863. The real art

critics and artists are not deceived. The young Monet, who at this

time does not know its author, suffers a real shock. The Saul of Impressionism

finds his road to Damascus. But reaction only really breaks out on 15

May in the same year when Manet exhibits "Dejeuner sur l'Herbe"

at the Salon des Refuses in the Palace

of Industry, which the Emperor had generously allowed to be held because

of the extreme conservatism of the French

Academy in the form of the Salon jury. This hysteria was to last three

or four years, renewed again at the Salon

of 1865 by "Olympia,"

painted in 1863.

Today it is almost impossible to understand

how these two paintings could have inspired such gross insults and such

violent taking of sides. The arguments have been brought up so many times

that we may dispense with reviving them again; they are of no interest

in themselves, in their monotonous repetition, nor because of their authors,

who are now completely forgotten. This violence can only barely be explained

by a sort of diffuse realisation of the importance of Manet, of the role

he was to play without knowing exactly what. It allows the rage of his

enemies to be measured.

Among the pretexts which may have caused

it, I can see barely one, which Manet undoubtedly did not want, but which

resulted from the technique of contrasts which he had elaborated: the

nudes at the centre of the two paintings no longer have anything of the

conventional drawing school figures but, with their lewd whiteness, evoke

a sensation of undress which, placed in the surroundings of daily life,

profoundly stirred the hypocrisy of the period. (Let us recall the outraged

Empress slashing with her cane at the buxom nude in Courbet's "Source.")

These white colours today remain striking whereas their contemporaries

saw them as dirty.

Whatever the pretext it could not have been a worse choice. The two compositions,

as more far-sighted and cooler minds were soon to show, were inspired

by the most classic of Renaissance

models: "Judgment of Paris," by Raphael,

made popular by the engravings of Marcantonio Raimondi. Undoubtedly in

"Dejeuner sur l'Herbe" there is a shock effect in the alternation

of nude and dressed figures (one of them rather comic in an indoor jacket

and tasselled cap), representing rather a succession of moments than a

homogeneous group. The landscape is presented also a little like a decor

of successive plantings, from which the luminous backgrounds are lit up.

What strikes us most today about this hybrid work is the extraordinary

still life in the foreground, spread out on the blue clothing. "Olympia,"

on the other hand, is a work of wonderful unity in which all the elements

are linked together without the slightest break and flow together to give

the impression of sumptuousness to this slight, slender body. The expanses

of lightness - the mat flesh, yellow and pink wrap and bluish sheets -

are relieved by several elements of black, more and more intense up to

the ribbon above which the head appears to be cut off. All this is spread

out with regal cleverness. It is a showpiece perfectly executed and it

is easily understood why Monet did not hesitate later to choose it as

the object of a national subscription to be offered to the Louvre.

From the time it is shown, Manet's triumph is assured. And in fact in

this year of 1865 what could anyone put in his way? Hence the impotent

rage of some people. Thus Manet is alone. He carries everything before

him.

Of the other painters of his age, Degas

exhibits another of his great classical compositions, "Misfortunes

of the City of Orleans," on which the eminent artist Puvis

de Chavannes congratulates him. Cezanne

has yet to properly emerge. Of the other Impressionist

painters (ten years younger than Manet), the most important group,

that of Monet, Sisley,

Renoir and Bazille, have barely come out of the Gleyre studio and as yet

have had little chance to show what they can do. It is there, however,

that the succession is being prepared, thanks to supporters like Paul

Durand-Ruel. For more, see: Best

Impressionist Paintings.

NEXT: (4) Impressionist

Claude Monet.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the use of an excerpt from Impressionism,

by Jacques Lassaigne (1966).

|