|

IMPRESSIONISM

OUTDOORS

For a review of outdoor scenic

works, see Landscape Painting,

and the French

Barbizon School.

For a review of Impressionism

and plein-air art, see:

Impressionist

Landscapes.

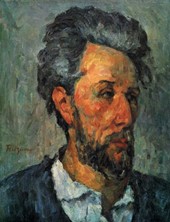

IMPRESSIONISM & PORTRAITS

For information and examples

of portraiture, please see:

Impressionist Portraits.

PAINTING

For more about the evolution

of oils, acrylics, watercolours

and other types of paintings,

as well as famous artists, see:

Fine Art Painting.

MEANING OF ART

For a discussion of the types,

values, and significance of the

visual arts, see: Definition of Art.

WORLD'S GREATEST

ARTWORKS

For a list of the Top 10 painters/

sculptors: Best Artists of All

Time.

WORLD'S TOP PAINTERS

For details of the best

modern painters, see:

Famous Painters.

BEST IMPRESSIONIST

ART

The best collection of Impressionist

and Post-Impressionist paintings

hangs in the Musee d'Orsay Paris.

|

The Impressionist

painters themselves are far from Paris, isolated and settled more

permanently to paint and develop their work. Sisley

is at Saint-Mammes, near Moret and the Loing Canal. Monet

is at Givemy near Vemon, in the Eure, with the widow of Hoschede, who

is to become his second wife (Camille died in 1878, worn out by privation

and difficulty). Pissarro

has settled at Eragny, in the heart of the Vexin. Cezanne

most often lives at Aix where his family life finally became stable, excepting

the death of his father, by his marriage to Hortense Fiquet. He works

in the solitude of his property Jas de Bouffan. Only Renoir

pursues a different sort of life, spending ten years as a sort of mental

and physical vagabond before finally choosing the Mediterranean coast

as the setting and model for the Eden which blossoms out of his creation.

But even so it must not be thought that

the painters have completely withdrawn into themselves. Some bitter ideas

in the minds of some of them cannot make them forget that their solidarity

remains deep, and that friendship continues to keep them together to a

varying extent. They visit one another in their travels and sometimes

spend long periods at each other's homes. Renoir goes a number of times

to Cezanne's place (in 1882, 1883, 1888 and 1889), once accompanied by

Monet, and Cezanne in turn visits Renoir at La Roche-Guyon and Monet at

Giverny. Later strong ties link their children, but they are already like

part of the same family. They exchange ideas and experiences, and so much

the better if these do not agree. They attach the greatest importance

to opinions formulated on their own works.

They remain bound by what they have lived through and helping those of

them who have passed on. For more on the subject of their artistic aims,

see: Characteristics of Impressionist

Painting 1870-1910.

Monet's efforts ensure the success of a

subscription opened to purchase Manet's "Olympia" and offer

it to the Luxembourg Museum in 1890. In the same way Renoir, executor

of the will of Gustave

Caillebotte, succeeds in overcoming the reservations of the Fine Arts

Administration and having them accept (although sadly only thirty-eight

out of sixty-seven paintings) the legacy of this magnificent collection

to the State. In 1895 it is the insistence of Pissarro which persuades

Vollard to organise the first Cezanne exhibition, which in one showing

reveals the gigantic stature of the painter.

But preoccupied with the completion of their own personal works in their

remaining years of life, the painters are indifferent to new research

and the younger personalities who appear alongside them and by whom they

may soon be regarded as outshone. But we shall see in the latter part

of this work how Cezanne, Degas, Renoir and Monet survive their immediate

successors and how their work, after having sometimes been regarded as

anachronistic and outdated, keeps an unsurpassed presence and strength

and, after years of eclipse, a surprising up-to-dateness.

Only Pissarro, always generous and enthusiastic, keeps in touch with the

painters of the new generation who come to the fore after 1880. It is

he who fosters the late-developing vocation of Gauguin

and gives him all his help as Gauguin develops from a week-end painter

and collector to a detested artist. Gauguin comes to work alongside him

in Rouen in 1883. Pissarro becomes interested shortly afterwards in Georges

Seurat who, with all the conviction and ardour of a tyro, devotes

himself to giving a rigorous scientific base to the victories of Impressionism

and who, in 1884, founds with a group of artists rejected by the Salon

a new association of "Independents", in which each may exhibit

freely without submission to a jury. Pissarro meets him in 1885, as well

as Signac, who has asked Chevreul to amplify his interpretation of the

laws which the Impressionists have applied more or less scientifically.

Considering this more precise formulation to be a step forward, Pissarro

does not hesitate to adhere to the system drawn up by the younger men.

He decides to exhibit with the Independents and puts Seurat and Signac

into the last showings by the Impressionist group, which take place in

1886.

In fact at the time when Durand-Ruel is attempting his New York exhibition,

Berthe Morisot believes

it would be appropriate to show the importance of Impressionists as a

group in a parallel exhibition in Paris. Pissarro, who alone had taken

part in all the previous showings, asked to be allowed to exhibit with

his new friends. Monet, followed by Renoir, Caillebotte and Sisley, preferred

then to withdraw and take part in the International Exhibition organised

at the same time by Georges Petit. Thus was the final exhibition of the

Impressionist group dominated by Pissarro and through him it opened the

way to the future. He showed twenty canvases in his new style and Seurat's

composition "La Grand-Jatte" and his Grandcamp landscapes caused

a sensation. Seurat and Signac had been accepted by Durand-Ruel for the

New York exhibition. The publication by Felix

Feneon of an important article The Impressionists in 1886, which announced

the passing of Impressionism and took the side of Seurat and Signac, for

whom the critic invented the name "Neo-Impressionism",

marked an important turning point.

|