|

|

In the first stage, he devotes himself

to fixing his impressions on detailed and almost elementary subjects.

He boldly places his still-life on white cloths which accentuate the shapes,

and the brilliance of colours is heightened by the use of black patches,

which he borrows from Manet. His first portraits, laid on in a thick paste,

with figures sometimes as large as life, stick strictly to the ideological

aim that he is pursuing. His father reading a novel stands out in front

of the whitish covering of his armchair. His friends Zola and Alexis are

curiously placed on a seat and cushions like oriental sages, divested

of all useless accessories or decor. (One cannot help thinking on the

other hand of Manet's portrait of Zola, almost contemporary, in which

the face counts for little while the composition includes everything calculated

to represent the man, his tastes and what interests him.) In this light

Cezanne's work then appears singularly bold and innovationist, which is

the main thing about it.

Cezanne is also the connecting

link between the future Impressionist

painters and the man who is to become their first ideological defender,

Zola. It is in innumerable discussions with Cezanne that Zola understands

the importance of Manet and realises the part he could play on his side.

In fact in 1866, the Salon jury, not wishing to see a repetition of the

Olympia scandal, reject all Manet's entries, including the "Fifer,"

at one swoop. Zola, who had agreed to write reviews of the Salon

for the new daily "L'Evenement," commenced his articles with

two attacks on the jury. In his third article he defines his own conception

of a work of art as being a combination of two elements, one fixed and

real, nature, and the other individual and subjective, the temperament

of the artist. He warns courageously against a conception too skimpy in

realism which, he says, is nothing unless it subordinates realism to temperament.

Having laid down these principles and even before beginning to review

the works exhibited, he devotes the whole of his fourth article to Manet

who in fact has been excluded from the exhibition. He puts on paper his

admiration not only for the "Fifer" but for earlier paintings:

"Le Diner sur L'Herbe" (as it was first titled) and "Olympia,"

and concludes by asserting that Manet's place, like that of Courbet, is

in the Louvre. Protests by readers

and subscribers are so strong that the editor decides to reduce the number

of articles by Zola and replace them with those of a more conformist critic.

Zola does not even write the three remaining articles commissioned from

him and, after a brief eulogy of Camille Corot (1797-1875), Charles

Daubigny (1817-78) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), ends his contribution.

But he publishes the whole of his articles in a booklet which he dedicates

to Paul Cezanne with whom he declares he will pursue alone the talks they

have had over ten years of life, often together, on the great problems

of artistic creation.

A year later, before the opening of the Universal Exhibition in which

Manet, like Courbet, has decided

to participate by renting a private stall in which he can show his works

quite freely, Zola publishes a long study of Manet and his works in which

he notes very pertinently the new contribution the artist has made to

art. As far as he is concerned Manet's forte lies in painting in solid

masses, of having discovered the tache (smudge), of always starting off

on a clearer note than exists in nature. He sees very clearly that in

the first and somewhat hard impression Manet's painting only shows delicacy,

that his colours are never piled up, nor are his effects forced, that

his values are true, his pallors strong and his simplicity quite up to

Museum standard. He comments impartially on his works, seeing in "Olympia"

the flesh and blood of the painter and emphasising the importance of his

new seascapes.

Today there is nothing much to change in these lines although they were

written while Manet was only halfway through his life's work. Simply remember

this definition by the painter Severini: "Here is the new process

of the tache, the exclusive search for tone and the new harmony of violet

shades. One might say that procedure counts little in art, that from Monet's

has come all modern painting."

Impressionist

Meetings in the Cafe Guerbois

Manet's pavilion in the exhibition of 1867

was not the success he had hoped for, while Courbet's, with some 110 works,

drew much more attention from the public as Manet's revived old quarrels.

In Manet's showing, however, is the essence of his work in fifty paintings,

presented in the most dignified and modest way with the painter simply

inviting the public to view "some sincere works". This exhibition

allows all the younger painters to measure the importance and the extent

of Manet's work. Only he was able to present so new and so significant

a collection of works. Even the idea of an exhibition was to be retained

by his comrades. Monet and his friends thought of taking a pavilion after

the exhibition closed to show, in their turn, works which could be presented

in a systematic fashion without the disadvantage of a neighbouring show.

Even if they were unable to find the money to stage the exhibition, it

still remained their aim. Zola's intervention on the side of Manet also

was to have lasting effects and give a theoretical adhesion to the meetings

of the young artists and writers.

Manet was in the habit, like other men about town of the period, of frequenting

a special cafe in the evening: first it was the Cafe de Bade at 26 Boulevard

des Italiens. But this cafe has many customers, of various types. Then

he shows a more marked preference for a smaller cafe at 11 rue des Batignolles

(now the Avenue de Clichy), the Cafe Guerbois. There he and his artist

and writer friends get into the habit of meeting. They are to be found

there every evening, according to individual liking, but every Thursday

they were all there. Manet was the elder, the leader, but while brimming

over with vivacity, always keeping to politeness and exquisite refinement

in discussion. Among those who were in the habit of meeting there were:

writers and critics like Zola, Duranty, Astruc, Duret, Burty, and Cladel;

artists like Fantin-Latour, Guillemet, Bracquemond, Degas, then Bazille,

Cezanne, Sisley, Monet, Pissarro and Desboutin; and just friends such

as Commandant Lejosne, the musician Maitre and the photographer Nadar.

At these brilliant meetings where wit flowed, sometimes sharp, Manet and

his writer friends, as well as Degas - redoubtable in discussion despite

his insistent monotone - at first had the lion's share of the discussion.

But gradually problems purely of pictorial interest, mainly of technique,

seem to take over and are debated with much seriousness. Monet, who listened

more than talked, perhaps shy from his upbringing, expounded his many

experiences. Cezanne interrupted with a vehemence sometimes not quite

understandable, to emphasise what he considered essential. Renoir, whose

mind was not theoretical, expressed his own personal non-conformist ideas

with humour and in a natural manner. Pissarro, who sometimes came up from

Louveciennes, impressed everyone with the generosity of his ideas and

the indomitable good nature of his convictions. From their discussions

and differences of opinion the group emerged more united and more friendly

and began to assume a well-defined shape. The meetings at the Cafe Guerbois

assumed importance from 1867 onwards and must essentially date from 1868

and 1869. If they did not survive the war it was because they had already

achieved their object: to permit the artists to know one another better

and to define their positions more clearly. At this stage discussion among

the artists had to give way to work. Moreover, it is symptomatic that

Fantin-Latour should

have preferred to place the group and his friends in a setting not in

the cafe but in an ideal imaginary studio. In this canvas, "A Studio

in Batignolles," painted in 1869 and exhibited in 1870, Manet is

sitting painting, surrounded by Renoir, Bazille, Monet, Astruc, Zola and

Maitre, and also the German painter Scholderer. In fact there were many

such meetings, not at Manet's place but at Bazille's studio. Bazille had

become installed near the Cafe Guerbois and left a small painting from

1870, free as a sketch, showing his friends and himself chatting and working.

In this work Manet and Monet are seen discussing the canvas which Bazille

is painting while Maitre plays the piano and Zola talks with Sisley. It

was Manet who painted the figure of Bazille.

See the art dealer and Impressionist

champion Paul Durand-Ruel.

Paintings by

Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro, Degas and Cezanne

LANDSCAPES

• Chemin

de la Machine, Louveciennes (1873) by Alfred Sisley.

Musee d'Orsay.

• The

House of the Hanged Man (1873) by Paul Cezanne.

Musee d'Orsay.

• Misty

Morning (1874) by Alfred Sisley.

Musee d'Orsay.

• Vegetable

Garden with Trees in Blossom, Spring, Pontoise (1877) Pissarro.

Musee d'Orsay.

• Path

Leading Through Tall Grass (1877) by Renoir.

Musee d'Orsay.

• The Red

Roofs (1877) by Pissarro.

Musee d'Orsay.

• Snow at

Louveciennes (1878) by Alfred Sisley.

Musee d'Orsay.

• The Bridge

at Maincy (1879) by Paul Cezanne.

Musee d'Orsay.

• Mont

Sainte-Victoire Paintings (1882-1906) by Paul Cezanne.

Various art museums.

URBAN LANDSCAPES

• Canal St Martin

(1870) by Alfred Sisley.

Musee d'Orsay.

• Boulevard

Montmartre paintings (1897-8) by Pissarro.

Various art museums.

FIGURE PAINTING

• The Ballet

Class (1871-4) by Degas.

Musee d'Orsay.

• Absinthe

(1876) by Degas.

Musee d'Orsay.

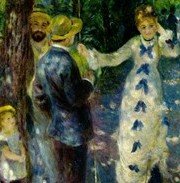

• Dance

at Le Moulin de la Galette (1876) by Renoir.

Musee d'Orsay.

• Luncheon

Of the Boating Party (1880-1) by Renoir.

Phillips Collection, Washington DC.

• The

Boy in the Red Waistcoat (1889-90)

E.G. Buhrle Collection; MOMA; Barnes Foundation; NGA Washington DC.

• Man

Smoking a Pipe (1890-2)

State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

• Woman

with a Coffee Pot (1890-5)

Musee d'Orsay, Paris.

• The

Card Players (1892-6)

Musee d'Orsay, Courtauld Gallery and others.

• Lady

in Blue (c.1900)

State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

• Young Italian

Woman Leaning on her Elbow (1900) by Paul Cezanne.

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

NEXT: (6) Claude

Monet and Camille Pissarro Travel to London.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the use of an excerpt from Impressionism,

by Jacques Lassaigne (1966).

|