|

|

In 1868, Monet has a brief respite from

his material worries. After Boudin succeeds in having him invited, with

Courbet and Manet, to an international maritime exhibition at Le Havre,

he sees his portrait of Camille bought by Arsene Houssaye, who has come

to the exhibition as Fine Arts Inspector, and meets a rich art-lover,

M. Gaudibert, who commissions him to paint a portrait of his wife and

helps him on several later occasions. This portrait, which appears to

sacrifice something to the worldly type of Alfred Stevens, a friend of

Manet and occasional visitor to the Cafe Guerbois, is, in reality, in

its treatment and composition very close to the contemporary portraits

by Manet himself, in which the individuality of the model disappears behind

a multiplicity of symbols and richness of decor. For instance, in the

famous portrait of Zola, the profile is an almost minor element compared

with the still-life formed by the ink-well, the open book, the coloured

brochures on the desk, or by comparison with the Japanese screen or with

the engravings mounted in a frame. In the portrait of Duret, the face,

inert as a sleeve or a hat, is reduced almost to nothing in comparison

with the enormous swollen silhouette. Animation returns to the hands and

there is intensity in the still-life in the foreground, the lemon and

the carafe: luminous spheres which provide a balance to the heavy vertical

mass of the body. In Monet's portrait of Madame Gaudibert, the head is

almost completely turned and what counts is the elegance of the puce silk

robe, the movement of the shawl, the bouquet of flowers, the curtains

painted with great sweeps of the brush and relieved with deep blacks.

But Manet, better than Monet, knows how to get rid of useless accessories.

Taking a lesson from Spanish painters, in whose work opposition of blacks

and live colours is magnified by their standing out against neutral backgrounds

of light and cloudy ochres, he places his figures in such a setting. The

most striking example of this before the portrait of Duret is his "Fifer,"

so concrete and striking in the brilliant colours of the uniform, but

suspended in a void.

At the end of 1868 Monet is at Bougival

with his family, once more without money and appealing desperately to

his friends. Renoir, who lives with his mother at Ville-d'Avray, comes

to work alongside him but is just as badly off, and often they have to

stop work through lack of paints. However, they sense that at the ends

of their brushes are ideas for wonderful canvases.

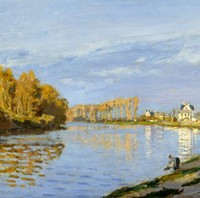

Their impressions are complementary and,

working on the same subject, they are to produce for the first time parallel

visions of immense interest, with each keeping his characteristic traits

and both trying to create a method of painting. First, it is the theme

of the boat and the water reflecting the houses and trees on the bank.

Then follow the unforgettable paintings of La Grenouillere. From this

point one can readily date the birth of Impressionism as a new technique

for possible general application. That celebrated place on the Seine near

the Fournaise restaurant, described by De Maupassant, presented an extraordinary

scene of liveliness which fascinated the two friends. The landing stage,

a little island with a single tree, provides a central point for composition

in which they show the strollers and the elegant coming and going. In

the works of these two Impressionist

painters, differing but at the same time close to one another, only

the treatment of the water is almost the same, with elongated strokes

producing alternation of light and shade according to whether the water

receives the full light and reflects it, or ripples from the shady side.

In the case of Renoir, figures merge into the overhanging foliage, an

almost indistinct coagulation of vegetation. People lose all individuality,

enveloped in delicate shades and reflections of light. In Monet's work,

on the contrary, the contrasts are very much more marked. Magic also exists

in his canvases but the composition is always clear with the whites exactly

divided. The decor of trees unfolds as a frieze in full focus, thus creating

a depth in front of which the silhouette of the island and, on the right,

the forward part of the restaurant, are detached. There are details of

prodigious boldness like the bathers on the left who seem to be streaked

by the light patches on the water. This masterpiece was rejected by the

jury of the Salon in 1870 despite the insistence of Daubigny, who resigned

over the affair. From this time also date the significant snow studies

in which Monet and Renoir probed the reflection of sunlight on snow, tinted

with pink or yellow and producing bluish or mauve shadows. See: Best

Impressionist Paintings.

Must we see in the lack of understanding that greeted Monet a measure

of the erosion of the society of that time? In this end of the Second

Empire there is a general indifference, and anxiety as well; nobody believes

in anything much any more. The forces of the future already exist. They

are preparing themselves, re grouping, and soon will burst out. But as

yet there is nothing for them but ignorance and scorn. What is pathetic

about Monet's struggle against adversity is the fact that a little more

understanding on the part of his family would have made it unnecessary.

His parents do not lack money and they could have given way, if not to

the already assured qualities of their son, then at least to his courage

and perseverance.

His position becomes almost untenable when,

in 1867, his companion Camille, whom he was unable to marry before 1870,

bears him a son. There are times when Monet is without even a fire, or

bread. His family will only consent to help him if he eats humble pie

and returns under their wing. He is offered food and shelter, but only

for himself and not for Camille and their child. He endures almost martyrdom

to try to produce, under so many difficulties, the work in which he believes.

His sole support is Bazille, who never tires of being asked for help,

in whose studio Monet sometimes takes refuge for long periods, and who

tries all ways of finding buyers for Monet's paintings and, when he fails,

sometimes buys a rejected work himself on instalments. (But read about

Monet's next patron, the art dealer Paul

Durand-Ruel.)

Related Articles

Later works by Monet include:

• La

Grenouillere (1869) Metropolitan Museum, NY.

• The

Beach at Trouville (1870) Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford CT.

• Impression,

Sunrise (1873) Musee Marmottan-Monet.

• Poppy

Field (Argenteuil) (1873) Musee d'Orsay.

• Gare

Sainte-Lazare (1877) Musee d'Orsay.

• Rouen

Cathedral paintings (1892-4) Various art museums.

• Water

Lilies (Nymphéas) (1897-1926) series of paintings, various

museums.

• The

Water Lily Pond: Green Harmony (1899) Musee d'Orsay.

NEXT: (5) Impressionists

Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro, Degas, Cezanne.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the use of an excerpt from Impressionism,

by Jacques Lassaigne (1966).

|