Early Renaissance Art

Definition, History, Characteristics, Artists.

MAIN A-Z

INDEX - A-Z of the RENAISSANCE

|

Early Renaissance Art |

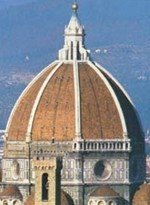

The Dome of Florence Cathedral, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi. A masterpiece of Christian art from the Early Renaissance. |

Early Renaissance Art (Italy) (1400-1490)Contents • What is the

Early Renaissance? Note: for more about the duomo - the icon of the Florentine Renaissance - see: Florence Cathedral, Brunelleschi and the Renaissance (1420-36). |

|

EARLY RENAISSANCE

HISTORY |

What is the Early Renaissance? - Characteristics Early Italian Renaissance art began to emerge in Florence during the first decade of the 15th century. Building upon Proto-Renaissance art, including the work of Proto-Renaissance artists like Cimabue and Giotto (see the latter's Scrovegni Chapel frescoes, especially The Betrayal of Christ (1305) and The Lamentation of Christ (1305) - as well as the Pre-Renaissance painting of Duccio di Buoninsegna) - Florentine and other Tuscan artists such as Filippo Brunelleschi, Donatello, Masaccio and Andrea Mantegna, instigated a series of discoveries and improvements in all the visual arts (architecture, sculpture, painting), which effectively revolutionized the face of public and private art in Italy and beyond. It even influenced the conservative Sienese School of painting in Siena. Although it eventually spread throughout Italy, the Early Renaissance was centred on Florence and patronized by the Florentine Medici family. Towards the end of the century, the movement reached its high point during the period known as the High Renaissance (c.1490-1530): notably in the works of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo and Titian. (Note: the term "Renaissance", used to describe the upsurge of Italian art and culture, during the period 1400-1530, was first coined by the 19th century French historian Jules Michelet 1798-1874.) |

|

PAINT-PIGMENTS,

COLOURS, HUES |

|

RENAISSANCE FIGURATIVE

ART EVOLUTION

OF VISUAL ART WORLD'S GREATEST

ARTWORKS RENAISSANCE: NORTH

EUROPE |

A Return to Classical Values of Humanism For reasons which remain unclear, there arose in Florence a new desire to cast off the old ways of thinking - in philosophy, religion and art - and begin anew. The model chosen by Florentine artists and intellectuals for this 'new approach' was that of Classical Antiquity. Why? Because they believed that Greek and Roman art constituted an absolute standard of artistic worth. This classicism was also consistent with the new mood of 'Humanism' which arose in Italy at this time. Humanism was a way of thinking which attached more importance to Man and less importance to God. Although Christianity remained the only religion, Humanism reinterpreted it so as to give it a human face. Thus, for example, religious figures like Evangelists, Saints, Apostles and the Holy Family were portrayed as real-life people, rather than stereotyped and idealized figures. Humanistic philosophy placed Man at the centre of things, and in the visual arts this led to a close study of the human body, a return to the nude and, leading on from this, a preoccupation with nature in all its forms. |

|

|

Developments in the Visual Arts The adoption of Classical values and the new philosophy of Humanism led directly to a series of changes in the creation of art - especially, architecture, painting and sculpture. Architecture Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) was the most influential designer of Renaissance architecture in Florence during the first half of the 15th century. His studies of Roman architecture (from the Roman architect Vitruvius) and mathematics gave him an insight into Classical methods of proportion and structure which he applied to pioneering technical achievements, such as his design for the dome of Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria Del Fiore), which was the highest of any church in Tuscany. Brunelleschi's cupola design was considered one of the finest engineering feats since Roman times. He is also credited with the revival of the classical columnar system, which he studied and mastered in Rome. Like many artists of the Early Renaissance, he excelled in several artistic activities. He was an accomplished sculptor and was also famous for his pioneering work into mathematical or linear perspective, which influenced many later painters of the period. See also: Greek Architecture (900-27 BCE). |

|

|

Greater Realism in Painting In keeping with the importance of Humanism, Early Renaissance painting strove to achieve greater realism in all their works. In contrast to the flat, stiff images of Byzantine art, faces now became more life-like, bodies were painted in more realistic postures and poses, and figures began to express real emotion. At the same time, great efforts were made to create realistic 'depth' in paintings, using scientific perspective. Although Giotto made advances in perspective, it wasn't until the arrival of the architects Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) that it was formalized as a creative technique and became a major preoccupation for many painters. Greater realism in fine art painting also necessitated proper study of light, shadow, and human anatomy. Although significant advances were made in these areas during the early and mid-15th century, it wasn't until the end of the century that light and shade (sfumato) was fully mastered by such great High Renaissance artists as Leonardo Da Vinci.

Subject matter also changed. Although most works were religious paintings illustrating Judeo-Christian stories from the Bible, Early Renaissance artists also introduced narratives and characters from Classical mythology, such as Venus and Mars, in order to illustrate their humanistic beliefs. It is noteworthy that whereas during earlier Medieval times, everything about Greek art and mythology was perceived as being pagan or associated with paganism, in the Renaissance it was identified with enlightenment. Sculpture In their quest for greater realism, Early Renaissance sculptors took inspiration directly from Classical Roman and Greek sculpture. But they were not slavish imitators. They imbued their free-standing figures with a range of emotions and filled them with energy and thought. Symbolism was often added to give extra meaning, in line with the new idea that sculptors (like painters) were the new creative intellectuals. The greatest sculptor of the period was Donatello (1386-1466), who along with the architect Filippo Brunelleschi and the painter Tommaso Masaccio made up the three dominant figures of the Florentine Renaissance. History of the Early Renaissance The Early Renaissance began arguably in Florence in 1401. In that year, a contest was staged to decide who would be given the commission to create a pair of bronze doors for the Baptistry of St. John - one of the oldest surviving churches in the city. Seven sculptors were selected: each was to design a bronze panel depicting the story of the Sacrifice of Isaac. Of the entries, only two have survived: those by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455) and Brunelleschi. In each, key elements of the new Renaissance style are already unmistakably present. Ghiberti's submission, showing a muscular Isaac derived from Classical originals, won the competition and he was duly awarded the commission for the doors, which took him 27 years to finish. A second similar commission followed, detaining Ghiberti for another 25 years. However, his gates became a visible symbol of Florentine art, causing Michelangelo to refer to them the Gates of Paradise. In 1425, Tommaso Masaccio began painting a series of fresco paintings depicting the Life of St. Peter in the chapel of the Brancacci family, at the Santa Maria del Carmine Church in Florence. Masaccio's dignified monumental style - dramatic but stripped of all ornament - portrayed intensely real-life characters exuding dignity and self-assurance. His figure painting of Adam and Eve being expelled from Eden is famous for its realistic depiction of their bodies and heart-rendering emotion. In 1428, he left the chapel before the series was finished (it was later completed by Filippino Lippi), and died suddenly in Rome three months later at the age of 27. Although he left behind only a small number of works, they were considered milestones in the history of art, and inspired many artists throughout the quattrocento. In later years, the Brancacci Chapel frescoes became a sort of gallery and training school for painters, including Michelangelo Buonarroti, whose Sistine Chapel frescoes were greatly influenced by Masaccio's work. In addition to his bold realism, Masaccio was also the first painter to understand and use scientific perspective. In his Holy Trinity fresco, painted around 1428 in the church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Masaccio implemented some of Brunelleschi's ideas about linear perspective, and created a convincing illusion of a chapel - the first major example of linear perspective of the Renaissance. Perspective was taken up by many of Masaccio's contemporaries of Masaccio, including Paolo Uccello (1397-1475), whose works such as, The Battle of San Romano (1438-40) and The Hunt in the Forest (1465-70), while dominated by artificial techniques of depth, still retain a joyous decorative enthusiasm. In this sense, Uccello combines International Gothic decoration with the more scientific Renaissance idiom. |

|

Piero della Francesca (1420-92) was another artist of the early Renaissance who experimented continually with perspective. He had a passionate interest in mathematics which he used to construct geometrically exact spaces and strictly proportioned spaces. His technique is best seen in The Flagellation of Christ (1450s), in which he combined tempera and oil painting - being one of the first to adopt the new medium of oils. His shorter-lived contemporary Andrea del Castagno (c.1420-57) also developed Masaccio's idiom, both in its pictorial perspective and the sculptural quality of its figures. Another early oil painter was the Sicilian portraitist Antonello da Messina (1430-1479), who allegedly learned the method of oil painting used by Jan Van Eyck, and then introduced it to the Venetian Renaissance. Other important early Renaissance artists include: Gentile da Fabriano (c.1370-1427), the influential International Gothic style painter noted for his masterpiece The Adoration of the Magi; the innovative Giovanni di Paolo (1400-82); the enigmatic Domenico Veneziano (1410-1461) noted for the St Lucy Altarpiece; Fra Angelico (c.1400-55) the religious Religious painter, best-known for his frescos in San Marco convent - see, for instance The Annunciation (1450) - Fra Filippo Lippi (c.1406-69) another artist monk, best known for his frescoes in Prato and Spoleto cathedrals; and Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-94), the most popular fresco painter in Florence during the 1480s, and also an outstanding portraitist - see, for instance, his wonderful humanistic work Old Man with a Young Boy (1490, Louvre, Paris).

The Second Generation of Renaissance Painters Realism, linear perspective and new forms of composition were all further developed and refined by the next generation of Renaissance Old Masters, including Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1432-98), the Padua-born Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), the quadraturista Melozzo da Forli (1438-94), and the Florentine Alessandro Botticelli (1445-1510). Antonio del Pollaiuolo studied the complexity of human anatomy: see, for example, his masterpiece work, the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (1475). Andrea Mantegna, (taught by the antiquarian Francesco Squarcione) who was active in Verona, Rome and Mantua, devoted most of his time to the ruling Gonzaga family in Mantua. His Camera degli Sposi frescoes completed between 1465 and 1474 in the Ducal Palace, are considered to be among his greatest works. A master of illusionistic frescoes, the round ceiling mural painting in the Camera degli Sposi was a milestone in trompe l'oeil technique known as quadratura. Another example is the dramatically foreshortened figure of the dead Jesus in his masterpiece The Lamentation Over the Dead Christ (c.1470-80). The third major second generation painter was the sickly Alessandro Botticelli, whose style diverged from the fashionable realism, being instead dreamy, sentimental, and almost decorative in nature. In his paintings of the Madonna and her mythogical equivalent Venus, he created an unmistakable feminine ideal: slim, blonde, modest and slightly sad. Eschewing scientific perspective, Botticelli's paintings are characterized by dreamy unreality and distortion. His figures are instantly recognizable for their dignity and detachment. His two most renowned paintings are the Birth of Venus (c.1485) and La Primavera (c.1477-82). His later works were influenced by the fundamentalist preaching of Savonarola (1452-98). Other late figures in the Early Renaissance were the Perugian painter known as Perugino (1450-1523) - noted for his fresco Christ Handing the Keys to Saint Peter (1482), in the Sistine Chapel - who had a formative influence over the young Raphael, and Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522), whose fantasy realism was influenced by Flemish painters. In Venice, the leading figures of the Early Renaissance included Jacopo Bellini (1400-70), known mostly through his sketchbooks, and his sons Gentile Bellini (1429-1507) and Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516). It was Giovanni - one of the first major pioneers of oil painting in Venice - who became the father of Venetian painting and the teacher of both Giorgione and Titian, the supreme masters of 16th century art in the city. See, for instance, Bellini's wonderful Ecstasy of St. Francis (1480, Frick Collection, New York); his powerful study of Doge Leonardo Loredan (1502, National Gallery, London) and the richly coloured San Zaccaria Altarpiece (1505, Church of San Zaccaria, Venice). |

|

Early Italian Renaissance Sculpture The two greatest sculptors of the early Italian Renaissance sculpture were the Florentines: Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, more commonly known as Donatello (1386-1466), and Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-88) - the latter being somewhat overshadowed both by the earlier Donatello and by the later Michelangelo. Donatello, the indisputable pioneer of modern Italian sculpture, was (along with Brunelleschi and Masaccio) a pivotal figure in quattrocento fine art. He reinvented the medium of sculpture in much the same way as Masaccio, Piero della Francesca and Mantegna revolutionized painting, and in the process became famous throughout Italy. He could bring a statue to life by investing it with intense realism, and emotion. His masterpiece, the five feet tall bronze sculpture David (1440s), created for the Medici family and errected in the Palazzo Medici in Florence, was the first life-size nude since Antiquity. Wearing only a hat and boots, the slender almost feminine Biblical shepherd boy seems hardly capable of the violence needed to slay Goliath, yet he retains a hypnotic mystery for the spectator. The new Renaissance style is evident in both the Classical nudity and the use of Classical contrapposto (twist of the hips), as well as the boldness of interpretation. For more, see: David by Donatello (1440s, Bargello Museum, Florence). Andrea del Verrocchio's finest works rank with the statues of Donatello that inspired them. His David (c.1475) is more refined but less deeply thoughtful than Donatello's statue, while his equestrian statue of the condottiere Bartolommeo Colleoni (1480s) is less heroic but conveys a greater sense of movement and swagger than Donatello's statue Gattamelata statue of Erasmo da Narni (1444-53) in Padua. As well as sculpting, Verrocchio was an accomplished painter who ran one of the largest studio-workshops in Florence, with numerous pupils including a young artist called Leonardo Da Vinci. In many ways, the many talents of the early Italian Renaissance are personnified in the figure of Leon Battista Alberti (1404-72), one of the leading intellectuals of the period. Based in Rome for most of his career, where he held a post in the Papal Secretariat, he was a humanist philosopher, a Latin scholar, and the foremost art theorist of the Renaissance. His first treatise on painting, De Pictura (Della Pitura) (1435) in which he explained the concept of disegno, was followed by a second on architecture, De re aedificatoria (1440s) and a third on sculpture called De Statua (1460s). These books brought together all the innovations of his Renaissance contemporaries, and their publication helped to propagate the new ideas throughout Europe. A practical man as well as a theorist, Alberti was also a painter, sculptor and an inventive architect. His influential designs included the facades of Santa Maria Novella and the Palazzo Rucellai in Florence. Alberti also designed a number of churches in Mantua, including S. Andrea and S. Sebastiano. Although his direct contribution to painting and sculpture was relatively minor, Alberti's importance as a thinker and disseminator of ideas was no less important to the spread of the Renaissance than that of other more famous artists.

For details of how the movement developed in different Italian cities, see: • Renaissance

Art in Florence (eg. Masaccio, Brunelleschi, Leonardo Da Vinci); See also: Spanish Renaissance Artists. |

|

• For styles of painting and sculpture, see: Homepage. Art

Movements |