Portrait Art

History, Characteristics, Types of Portraiture.

MAIN A-Z INDEX - A-Z of PAINTING

|

Portrait Art |

|

|

Portrait Art (2,500 BCE - present)Contents • About Portrait

Art |

|

WORLD'S TOP PORTRAITURE THE VISUAL ARTS |

In fine art, a portrait can be a sculpture, a painting, a form of photography or any other representation of a person, in which the face is the main theme. Traditional easel-type portraits usually depict the sitter head-and-shoulders, half-length, or full-body. There are several varieties of portraits, including: the traditional portrait of an individual, a group portrait, or a self portrait. In most cases, the picture is specially composed in order to portray the character and unique attributes of the subject. Among Western Art's great exponents of portraiture are the Old Masters of the Renaissance such as the Florentines Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Michelangelo (1475-1564), and Bronzino (1503-72), the Tuscan Raphael (1483-1520), and the Venetian Titian (1487-1576). North of the Alps, there was Jan van Eyck (1390-1441), the founder of Flemish painting from Bruges, and the German portraitists Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) and Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543). Later exponents included the immortal Dutchman Rembrandt (1606-69) and the Baroque painter Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641), the Spanish court painter Velazquez (1599-1660), and the Englishman Thomas Gainsborough (1727-88). Modern portraiture is exemplified by Theodore Gericault, Edouard Manet; Paul Cezanne, Vincent Van Gogh, John Singer Sargent, Paul Gaugin, Pablo Picasso, William Orpen, Amedeo Modigliani, Otto Dix, Graham Sutherland, Lucien Freud, Chuck Close, and Frank Auerbach. The largest collection of portraiture can be seen in the National Portrait Gallery (London), which has some 200,000 examples. |

|

|

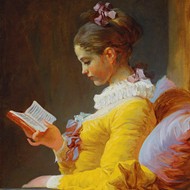

A Young Girl Reading (c.1776) By Jean-Honore Fragonard. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. A masterpiece of 18th century French painting by one of the great exponents of Rococo art. |

Ancient Portraiture Portrait painting can be considered as public or private art. In ancient Mediterranean civilizations, like those of Egypt, Greece and Rome, and Byzantium, portraiture was mainly a public art form, or a type of funerary art for Gods, Emperors, Kings, and Popes. Portraits were executed as sculpture in bronze, marble or other stone, or as panel paintings or mural frescoes. Although private artworks - typically for royal families - were commissioned during the Sumerian, Egyptian, and Greek era, most ancient portraiture was public art, designed to decorate public areas and reflect the morals and religious values of the day. |

|

Twiggy (1967) |

Examples of portraiture from early Egypt include: the sculpture, Menkaure and His Queen (c.2470 BCE); the sculptures, Pharaoh Akhenaten (c.1364 BCE), The Daughter of Akhenaten (c.1375 BCE), the bust of Nefertiti (c.1350 BCE); and the Mummy Portraits (c.200 CE). Greek sculpted portraits included: the marble bust, Socrates (c.340 BCE); as well as numerous busts, reliefs and statues of Greek Gods, from Aphrodite to Zeus. Important sculptors during the Classical Greek period were Polykleitos, Myron, and Phidias. Portraits were also painted on panels, although almost none of these have survived. A famous exception is the series of Fayum Mummy Portraits (c.50 BCE - 250 BCE) found in the Faiyum Basic near Cairo, in Egypt. Roman Portraiture Roman Art was based on practical political necessity. Portrait busts of all Emperors, from Julius Caesar to Constantine, were sculpted in marble or bronze. These statues and busts were displayed in public throughout the empire, to celebrate Roman power. A huge arts industry grew up in the capital, attracting sculptors, painters and artizans from all over Italy and Greece, simply to cope with this demand for imperial portraits. There are, for instance, more than 250 surviving busts of Emperor Augustus. Roman portraits continued the tradition of public art. |

|

Portraiture During Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages With the coming of the Dark Ages after the sack of Rome (c.450 CE), public art took a less conspicuous form. Portraiture as well as other types of paintings were created mainly for the insides of churches and monasteries, (typically in the form of fresco murals or encaustic panel paintings), or used to illustrate illuminated gospel manuscripts, like the Garima Gospels (390-660) from Ethiopia and the Book of Kells (c.800) from Ireland. The sole major patron of the arts for most of the Medieval era was the Church. Examples of works from this period include: encaustic panel portraits and icons from Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai, such as, Throned Madonna with Child (c.600 CE); portraits of the Evangelists and Apostles in Celtic Christian illuminated manuscripts and Carolingian gospel texts, like John the Evangelist (c.800). During the Romanesque and Gothic periods to the fourteenth century (c.1000-1300), portraiture widened to include stained glass art - much of it still visible today in architectural masterpieces like Chartres Cathedral and Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Giotto's Naturalism and Jan Van Eyck's Realism (c.1300-1450) The Byzantine style of portrait painting which dominated throughout the period 450-1400, was not compatible with true-life pictures. Instead, painters adhered to an hieratic style of art, in which the spiritual and human characteristics of a figure were to be inferred from symbolic motifs. This non-naturalistic approach went largely unchallenged until the arrival of Giotto (1266-1337) whose Scrovegni (Arena Chapel) frescoes were the first pictures to feature realistic, ordinary-looking people, with solid three-dimensional shapes. This new style soon made itself felt in portrait art proper: first, among oil painting experts of the Netherlandish Renaissance (c.1400-1580) and German Renaissance including Jan van Eyck, Roger van der Weyden, Lucas Cranach and Hans Holbein - oil paint being especially conducive to realistic looking pictures - and later France, with works like Portrait of Charles VII of France (1445-50) by Jean Fouquet (1420-81). By 1500, portraiture had become a major painting-genre. The Influence of the Italian Renaissance (c.1450-1530) Renaissance art introduced several new ideas into painting. These included technical concepts, such as linear perspective, light and shade (chiaroscuro and sfumato) and 3-D modelling, as well as narrative concepts, such as humanism. These ideas provided portrait artists with greater resources, which soon led to a noticeable rise in the quality of Renaissance portraits. Meantime, the Church maintained its hold over fine art patronage, commissioning works for cathedrals, churches, chapels, monasteries and convents. Indeed the Vatican almost went bankrupt during the 16th century as successive Popes spent fortunes decorating Rome. It goes without saying therefore, that most portraits during this time were of members of the Holy Family, Martyrs or Apostles. The influence of the Renaissance on portraiture endured for centuries, as artists continued to emulate the style of Leonardo, Raphael, Titian and Michelangelo. See also Venetian Portrait Painting (1400-1600). Post Renaissance Period (c.1530-1700) Two important developments occurred during the Mannerist (c.1530-1600), and Baroque (c.1600-1700) periods. During the 16th century, a clear hierarchy of paintings was established by the main arts academies - based on a picture's perceived 'inspirational' qualities. Five genres were ranked, as follows: (1) Historical, religious or mythological pictures (containing a 'narrative' or 'message') were seen as the worthiest genre, followed by (2) portraits, then (3) genre-paintings, that is pictures of everyday scenes, (4) landscapes and finally (5) still life paintings. Because of this, many portrait artists tried to enhance the standing of both their painting and their subject by giving their portraits an historical, religious, or mythological setting. In addition, during the mid-16th century, following the European-wide schism between the Catholic Church in Rome and the Protestant movement - caused by Luther's Reformation (c.1520) - the Catholic Council of Trent decided to launch a huge campaign to win back disillusioned worshippers. This campaign, known as the Counter-Reformation, used art as a propaganda weapon, and so commissioned a huge number of religious paintings and sculptures - many executed on a monumental scale - including some iconic portraits. See, for instance, El Greco's wonderful masterpieces Portrait of a Cardinal (1600) and Portrait of Felix Hortensio Paravicino (c.1605). See also: Baroque Portraits. For 17th century painters who specialized in portraits of kings, see for example Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743), noted for his portraits of Louis XIV. Dutch Realism School - A Unique Period of Portraiture Coinciding with the upsurge in Catholic painting, there emerged a mini-Renaissance in protestant Holland, fuelled by a new, highly materialistic type of customer - the rich middle-class merchant, or professional - who wanted to buy paintings that made him and his family look good. They had to be small enough to hang on the wall of his house, and detailed enough to appear true-to-life. Thus the inimitable style of Dutch Realism painting was born. The greatest Dutch Realist artists included wonderful portraitists like Frans Hals (1582-1666), Jan Vermeer (1632-75) and of course, Rembrandt.

Expansion of Portraiture: Yesterday's Photography (c.1700-1900) Portraiture greatly expanded as a genre during the 18th and 19th centuries. This was due to several factors, including: the universal use of oils and canvas; the increase in commerce which in turn created a large group of wealthy middle-class businessmen and landowners; and the use of portraiture as a way of making a permanent visual record of individuals and families. In any event, there was a significant growth in portrait art during this period, which was only halted with the introduction of the camera in the 20th century. For 18th century works, see: Rococo/Neo-Classical portraiture. Probably the two finest female portrait painters of the eighteenth century, were the Swiss artist Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807), who was active in London and Rome, and Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun (1755-1842), court painter to Queen Marie-Antoinette. Other exceptional eighteenth century portraitists include Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805) noted for exquisite Rococo works like The White Hat (1780, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). For 19th century paintings, see: Nineteenth century portraits. As far as specific schools are concerned, the features of English portraiture are discussed in: English Figurative Painting 18th/19th century, while you can also see examples of notable Impressionist portraits by the likes of Edouard Manet and others.

20th Century Portraiture The twentieth century showed little interest in the classical hierarchy of genres, and became absorbed with new ways of representing reality in an era of world wars and moral uncertainty. After a series of Expressionist portraits, advances in photography, film and video, made classical portraiture seem anachronistic and of little value. Instead, 20th century portrait artists simply used the genre as another means of promoting their style of art. Exceptions include Picasso's portraits such as Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906), and those by the expressionist Modigliani: see, for instance, Portrait of Juan Gris (1915) and Portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne (1918). Post-war developments have also been influenced by additional art materials, computer-based media and new forms of printmaking, permitting new works in acrylics, aluminium paint, collage form, silk screen prints, computer prints and mixed media, as well as a variety of new sculptural media. This trend is exemplified in Pop-Art portraits by Andy Warhol (1928-87), whose print portraits of Elvis, Marilyn Monroe, Jacqueline Kennedy, Elizabeth Taylor and Mao-Tse-Tung became icons of the later twentieth century. The latest contemporary style of portraiture, known as photorealism (hyperrealism) is exemplified by artists like the American Chuck Close (b.1940). |

|

Characteristics of Portrait Art Like any genre of painting, portrait art reflected the prevailing style of painting. In early Egypt, painted portraits and relief sculptures only showed the subject in profile. A portrait painted during the Baroque era would be more exuberant than the dignified Neo-Classical pictures, but neither was as down to earth as those of the Realists. Likewise, Romantic portraiture was more animated than Impressionist portraits, while Expressionist portraiture from the early twentieth century is typically the most garish and colourful of all eras. That said, in very simple terms one can detect two basic styles or approaches in portrait-painting: the 'Grand Style' in which the subject is depicted in a more idealized or 'larger-than-life' form; and the realistic, prosaic style in which the subject is represented in a more down to earth realistic manner. Styles of Individual Portraitists Although the greatest portraitists, like Leonardo, Michelangelo and Rembrandt mastered both styles, most artists tend to exemplify one tradition only. For example, those who painted in the Grand Classical style included: Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Sir Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641), Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92), Goya (1746-1828), and John Singer Sargent (1856-1925). William Orpen (1878-1931), one of the great Irish portrait artists also painted in the grand 'academic style'. Others specialized in a more down to earth portraiture, such as Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) and Jan Vermeer (1632-75), both of whom painted quiet precise works. The realist style was explored by Theodore Gericault (1791-1824), who produced realistic pictures of mentally ill patients, by the Russian genius Ivan Kramskoy (1837-1887) - noted for his humanistic realism - and by other Russians like Vasily Perov (1833-82). Impressionist portraitists include Frenchmen Edouard Manet (1832-83), Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Edgar Degas (1834-1917) and Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), as well as the Russian Valentin Serov (1865-1911) and the American John Singer Sargent - see his Portrait of Madame X (1884). Expressionist portraiture is exemplified by the emotionalism of Van Gogh (1853-90), the urban portraits of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), the lyrical primitivism of Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920), and by the black humour of Otto Dix (1891-1969) and Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980). More modern portrait painters include Graham Sutherland (1903-80), noted for his mood-portraits; David Hockney (b.1937) for his precision and form; and Lucien Freud (b.1922) for his raw naturalism. Meanwhile, the master of impasto Frank Auerbach (b.1931) continues to produce works of extraordinary intensity. |

|

During the history of Western Art, portrait artists have been employed for numerous reasons. First, in ancient Greece, Egypt and Rome (as well as in Mycenean, Minoan and other Mediterranean cultures), painters and sculptors were used to portray a wide range of Gods and Godesses, in a range of public artworks. Examples include: Aphrodite (c.350 BCE) by Praxiteles; the Venus de Milo (c.100 BCE); the Pergamon Frieze (c.180 BCE) as well as busts of Zeus, Pan, Eros and others. The Renaissance maintained this type of religious art through its fresco murals of Christianity, featuring the Prophets, Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary and the Apostles. Meanwhile, Leonardo Da Vinci's The Last Supper and Michelangelo's Genesis fresco (1508-12) and Last Judgment fresco (1536-41) - on the ceiling and walls of the Sistine Chapel in Rome - contain some of the greatest religious portraits ever created. Other noteworthy religious and mythological portraits of the Renaissance, including: Jan van Eyck's portraits of Adam and Eve in his masterpiece The Ghent Altarpiece (1425-32); Mantegna's Lamentation Over the Dead Christ (c.1490); Leonardo's Virgin and Child with St. Anne (1502); Raphael's Sistine Madonna (1514); and Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538). Although many of these works are not limited to a single face or figure, and some are viewable only at a distance, their aim was to pictorialize Christianity in personal form, and therefore should be regarded as part of the portrait genre. One should also note that the Renaissance attached the greatest importance to painting that portrayed a narrative or message. Thus artists typically included their 'portraits' within large narrative scenes. Portrait artists also depicted revered historical human figures. For example, all the Roman Emperors (eg. Julius Caesar, Augustus, Marcus Aurelius) were portrayed in public art forms, like statues, busts and friezes, in order to glorify the Roman Empire. Egyptian Pharaohs were also widely portrayed in various media, such as portrait busts, tomb carvings and Mummy portraits. Later Popes, Kings and Presidents were also commemorated in portraits, a process which flourished from the High Renaissance onwards. Examples include: Doge Leonardo Loredan (1502) by Giovanni Bellini; Pope Leo X with Cardinals (1518) by Raphael; Sir Thomas More (1527); Thomas Cromwell (1534) and Henry VIII (1536) by Hans Holbein. Emperor Rudolf II as Vertumnus (1591) by Giuseppe Arcimboldo; King Charles I of England Out Hunting (1635) by Anthony Van Dyck; Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650) and the complex Las Meninas (1656) by Diego Velazquez; The Suicide of Lucretia by Rembrandt; George Washington (1796) by Gilbert Stewart; Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801) by Jacques-Louis David; Wellington (1816) by Francisco Goya; Theodore Roosevelt (1903) by John Singer Sargent; American Gothic (1930) by Grant Wood; Study After Pope Innocent X by Velazquez (1951) by Francis Bacon. Another type of historical portrait - the 'political portrait' - is exemplified by Weeping Woman (1937, Tate Modern, London), the universal symbol of female suffering. |

|

Famous people have always been a sought after subject (or target) of professional artists, from the Renaissance to Pop-Art. Examples of portraitists and their pictures of celebrities include: Jan van Eyck: The Arnolfini Portrait (1434); Lucas Cranach the Elder: Diptych with the Portraits of Luther and His Wife Katherina von Bora (1529); John Singleton Copley: The Three Youngest Daughters of George III (1785, Buckingham Palace London); Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tisschbein: Goethe in the Campagna (1787); Joseph Lange: Mozart at the Pianoforte (1789); Sir Henry Raeburn: Sir Walter Scott (1823); Ilya Repin: Portrait of Leo Tolstoy (1887); Juan Gris: Portrait of Pablo Picasso (1912); Graham Sutherland: Portrait of Somerset Maugham (1949); Willem De Kooning: Marilyn Monroe (1954); Andy Warhol: Eight Elvises (1963). Other paintings of famous people include: the poet Anna Akhmatova painted by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin; the actor Charlie Chaplin by Fernand Leger; and Bolshevik leader Lenin by Isaak Brodsky.

From Classical Antiquity, through the Renaissance to the 20th century, both the male and female nude have featured in portraiture, in painting, sculpture and engraving - Botticelli's Birth of Venus (1485) being one of the greatest. Other celebrated nude portraits include: The Sleeping Venus (1510, Dresden) by Giorgione; The Venus of Urbino (1538, Uffizi) by Titian; The Rokeby Venus (1647) by Velazquez; The Valpincon Bather (1808, Louvre) and La Grand Odalisque (1814, Louvre) by JAD Ingres. For other famous examples, see: Female Nudes in Art History (Top 20) and Male Nudes in Art History (Top 10). Portrait artists were also commissioned by lesser nobles, cultural figures and businessmen to create a flattering likeness of them, reflecting their position in society. This type of easel-art flourished during the High Italian Renaissance, and in the Northern Renaissance among the Dutch and Flemish schools, as portable art media like panel paintings and canvases began to replace mural frescoes. Examples include: Duke Federico da Montefeltro and His Spouse Battista Sforza (c.1466) by Piero Della Francesca; The Family & Court of Ludovico II Gonzaga (c.1474) by Andrea Mantegna; Leonardo's Lady with an Ermine (Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani) (c.1490), and Mona Lisa (c.1503), wife of Francesco del Giocondo; Raphael's Baldassare Castiglione (1515); Jan van Eyck's Virgin of Chancellor Rolin (1436); Holbein's Erasmus of Rotterdam (1523, National Gallery, London); The Merchant Georg Gisze (1532, SMPK, Berlin); and The Ambassadors (1533, National Gallery, London); The Laughing Cavalier (1624) by Frans Hals; The Night Watch or The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq (1642) and The Syndics of the Clothmakers Guild (The Staalmeesters) (1662) by Rembrandt; Master Thomas Lister (1764) by Joshua Reynolds; Mrs Richard Sheridan (1785) by Thomas Gainsborough; Portrait of Monsieur Bertin (1832) and Portrait of Madame Moitessier (1844-65) by Ingres. Portrait of Miss Amelia Van Buren (1891) by Thomas Eakins; and Portrait of Miss Dora Wheeler (1883, Cleveland Museum of Art) by William Merritt Chase (1849-1916). Review of the Development of Portraiture There are many portraits among the masterpieces of European painting from the fifteenth century to recent times and they are an important feature of the work of masters who excelled in other genres. Goya (1746-1828), the painter of Spanish life, of the bull-fight, of popular festival, of sinister omen, of the disasters of war, even of religious subjects would yet be incomplete in our view without his brilliant studies of the individual personality. For the greater part of the medieval period, in an art dedicated to religion, such studies (had it been possible to make them) would have seemed an intrusion on the ground belonging to faith, an impertinence if nothing more. The sculptured effigies of kings and queens were memorial abstractions of authority. Manuscript illumination provided symbols rather than likenesses, until the later Middle Ages. The beginnings of characterization appear in royal portraits of the fourteenth century, the Wilton Diptych providing an example. Yet, beautiful work as it is in a delicate miniature style, seemingly related to that of the Franco-Flemish artist Andre Beauneveu (c.1330-1403), it poses a problem in the image it gives of the young and beardless Richard II. There is some evidence to show that the panel was painted at a later date when Richard was bearded and prematurely aged. Whatever the reason, this would imply that likeness was not such a primary concern as attitude and devotional content. In Flemish painting of the fifteenth century the realistic portrait comes into being with a startling suddenness. The practice of including the likeness of the donor - prelate, noble or wealthy merchant - in the altarpiece destined for church or convent exercised the superb skills of Jan van Eyck (1390-1441), Roger van der Weyden (1400-64) and Hans Memling (1433-94). They painted purely secular portraits with the same power, foreign visitors to the Flemish cities being among their clients. The agent of the Medici at Bruges, Tommaso Portinari, appears with his wife and children in the great Adoration, now in the Uffizi, by Hugo van der Goes (1440–82). Sir John Donne, knighted by Edward IV during the Wars of the Roses, was portrayed with his wife and daughter in the Donne Triptych (1477) by Hans Memling, now in the National Gallery, London. An Englishman abroad, Edward Grimston of Rishangles, Suffolk, had earlier been the subject of a purely secular painting by Petrus Christus (c.1410-1473), the follower of Van Eyck at Bruges. The fellow-feeling between England and the southern Netherlands thus extended to art was to have a sequel in the long succession of Flemish painters settling in London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Humanism, the Renaissance and the Reformation all contributed to the development of portraiture as an independent genre. The principle of the humanist philosophy that the proper study of mankind was man - logically gave the portrait a place of importance. The artists of the Renaissance were not only in accord with this view but by technical advance they improved the representation of character. The oil medium brought to Venice by Antonello da Messina (1430-1479) gave a new warmth and strength of modelling to the art. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) demonstrated how light and shade could add to the suggestion of personality and psychology (sfumato). The Reformation gave an impetus to portraiture of another kind. The suppression of religious imagery in the reforming lands made painters more willing to offer their services as portraitists. The career of Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) shows the effect of the three forces. Born at Augsburg, he chose to work when young in the German-Swiss city of Basel which as well as being prosperous was a centre of scholarly humanism. It was there he made his illustrations for the Praise of Folly by Erasmus. He had the Renaissance capacity for varied undertakings, from mural decoration and altarpieces to designs for goldsmith's work and stained glass, though his bent towards portraiture was already marked. But in the upsurge of Protestant feeling at Basel, employment of a Catholic nature came to an end. Like other artists he was 'without bread', as Erasmus observed in commending him to Thomas More in London. The interest of these friends (which he repaid by superb portraits of them) enabled Holbein to meet and portray in paintings and drawings a considerable sector of Tudor society in the two years of his first stay in England, 1528. His second stay of eleven years from 1532 to his death in 1543 brought him more definitely into the court sphere. He became painter to Henry VIII in 1536. No face in history is better known than the formidable visage with suspicious eyes and small cruel mouth painted by Holbein in the one picture (Thyssen Collection) - among a number of versions - that is certainly from his own hand. In this century of shifting relations and alliances between despotic rulers, the portrait had its diplomatic function. Besides providing a reminder at home to officials and courtiers of the governing power, the ruler-image was a symbol of international exchange, the artist himself an international figure. This was the position of Titian (1485-1576), the portrayer of Charles V and Philip II of Spain: and of Anthonis Mor (1519-1576), the Latin 'Antonio Moro', who later became Sir Anthony More and painted Mary Tudor and Sir Thomas Gresham. Before photography was invented - or personal acquaintance considered a necessary preliminary even to a royal marriage - the painted portrait served to convey the physical suitability of the prospective bride. Holbein was despatched to the continent to bring pack his pictorial report on the young but widowed Duchess of Milan and Anne, daughter of the Duke of Cleves, to assist Henry in making his choice. More than a description, his painting of the Duchess (London, National Gallery) became a masterpiece adding to the attraction of feature a splendid simplicity of design. Another purpose of the court portrait was to indicate power and rank by the splendour of costume and profusion of jewellery. This was strongly characteristic of the Elizabethan period, and perhaps a requirement of the patron that features should have a stiff and ceremonially expressionless aspect while the wealth of accessories gave evidence of status. The queen herself seems to have thought along these lines in her injunctions against shadow conveyed to Nicholas Hilliard, against, that is, the facial modelling shadow would produce. The almost Byzantine formal richness of such a work as the Ditchley Portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (1561-1636) was sought by court ladies in their lesser degree. The Flemish painters who came to England to escape religious persecution in the Netherlands and formed a Flemish colony in London were craftsmen supplying a requirement which limited their independence as artists. The genre of miniature portrait painting by its intimate scale avoided the heaviness of restriction, the art of Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619) in its clarity of colour, vivacity of delineation and emblematic poetry coming to the eye as melodiously as the Elizabethan sonnet to the ear. In turn Hilliard passed on his secrets to another of England's best miniaturists, the more modern Isaac Oliver (1568–1617). The seventeenth century was a great age of portraiture in Europe. The status of the painter was altered, he could claim a greater degree of independence in method and conception. The respect in which Titian had been held by the most powerful of rulers had left an abiding impression. The artist moved in court circles not as a hired workman but as one who added to their lustre. Where no court existed - in the United Provinces of the northern Netherlands - newly gained wealth and national freedom called for portraits in plenty. It has been said that every Flemish artist was a born portrait painter and to survey the course of Flemish painting from Van Eyck to Rubens and Van Dyck is to realize how much truth there is in this observation. Even so, the portraiture of Renaissance Italy had set a standard by which the seventeenth century profited. The Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione by Raphael (1483-1520) which Rembrandt (1606-69) saw at Amsterdam, suggested the style of composition he adopted in the self-portrait of 1640 (London, National Gallery). The eight years spent by Rubens (1577-1640) in Italy in the service of the Duke of Mantua, when he copied the great Venetians for the Duke and also for his own satisfaction, were years in which his originality was fostered by Italian example. During the six years spent by Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641) in Italy, painting portraits and studying the Venetians, he derived much from the dignity of pose and rich colour of Titian. Van Dyck can be viewed in two distinct aspects. There is the Baroque painter of emotional religious compositions that vie with those of Rubens in the churches of Antwerp, and there is the portrait painter more sensitive to psychological atmospheres than his master, Rubens. The coolness and restraint of England exerted their influence. The elegance and refinement of Van Dyck's art dominated the century in England, though William Dobson (1610-46) arrived independently at a vigorous style based on study of the Venetians, and Samuel Cooper (1609-72) stands out as one who could exquisitely reduce the effect of a large oil portrait to miniature scale. The decline of a 'court art' can be traced in the work of Sir Peter Lely (1618-80) and Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723). A race of aristocratic Parliamentarians and country gentlemen were the patrons in the period of England's greatest excellence in the portraits, the 18th century. The 18th century produced an informality and intimacy that Europe had not known before. The 'conversation pieces' practised by a number of artists - William Hogarth (1697-1764) foremost among them - give an example. Consisting of a family group or group of friends, they differed from such groups in Dutch or French art by showing the subjects informally engaged in some customary occupation or diversion in their usual surroundings. The pleasures of owning a country property are suggested by the portraits in open-air setting painted by Thomas Gainsborough (1727-88). The freshness of English beauty made its wholesome contrast with the elaborate make-up of the court ladies of old, while children were no longer portrayed as small effigies encased in ceremonial dress but in natural movement and expression. Instead of courtiers, a wide range of types and character appears. Hogarth for preference paints the middle-class philanthropist Captain Coram or a group of his own servants. Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92) paints the actor, the actress, the man of letters - Garrick, Mrs. Siddons, Dr. Johnson - as well as lords and ladies. George Stubbs (1724-1806) and others paint the sporting squires out hunting or shooting. There were still strong links with the past in the eighteenth century. Gainsborough came to the point when he rediscovered Van Dyck and re-fashioned the Flemish master's elegance in an English style, as the Scottish master Allan Ramsay had done before him. Reynolds gave his learned pictorial commentary on Rembrandt and Titian. The nineteenth century, less secure of its moorings, was more fitful and varied in style in the portraits that can be considered as works of art - leaving aside the large accumulation of works of an undistinguished and quasi-photographic character, product of growing population and middle-class wealth. The eighteenth-century tradition disappears in the temperamentally romantic brilliance of Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830). The Victorian Age presents such variations as the early portraits of Sir John Millais (1829-96) with their astonishing Pre-Raphaelite minuteness; the portraits of George Frederick Watts (1817-1904) which with some idealization well represent the intense earnestness of the Great Victorians; and the aesthetic conception of James McNeill Whistler (1824-1903) who viewed the portrait as an 'arrangement' of colours and shapes, rather than as a revelation of character. Of the Impressionists, Edgar Degas and Renoir excelled at poprtraiture - see: The Bellelli Family (1858-67) and the controversial Portraits at the Bourse (1879). See also the wonderful late portraits of Cezanne, such as: The Boy in the Red Vest (1889-90), Man Smoking a Pipe (1890-2), Woman with a Coffee Pot (1890-5), Lady in Blue (1900), Young Italian Woman Leaning on her Elbow (1900). NOTE: For an explanation of modern portraiture produced during the 19th century, please see: Analysis of Modern Paintings (1800-2000). The 20th century has witnessed the rapid decline of the painted portrait and the accompanying rise of the photographic portrait. Despite its technological background, the artistic value and aesthetics of this type of portraiture are in no way inferior. For a selected list of the greatest photographers involved in photograhic portraits, please see the following: • Julia

Margaret Cameron (1815-79) The next article covers Renaissance Portraits. |

|

• For other types of painting (portraits,

genre-scenes, still-lifes etc) see: Painting

Genres. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ART |