Russian Art

History of Icon Painting, Mosaics, Goldsmithing

and Architecture.

MAIN A-Z INDEX - A-Z of ART MOVEMENTS

|

Russian Art |

|

|

Russian Art (c.22,000 BCE - 1920)Contents • Oldest Russian

Art • For a list of the greatest painters

and sculptors from Russia, |

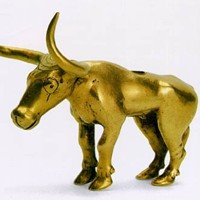

Maikop Gold Bull (c.2,500 BCE) Beautiful Russian goldsmithery from the Black Sea Bronze Age. For more modern Russian statues, reliefs and other 3-D objects, see: Russian Sculpture (c.1740-1940). |

|

EVOLUTION

OF VISUAL ART WORLD'S GREATEST

ARTWORKS |

Fine art in Russia dates back to the Stone Age. The earliest known work of Russian/Ukrainian art is the Venus of Kostenky (c.23,000-22,000 BCE), a mammoth bone carving of a female figure, discovered in Kostenky (Kostienki), dating from the Gravettian culture. A similar piece of prehistoric sculpture, carved out of limestone rock was discovered at the same site. Other items of Russian prehistoric art from the Gravettian era include the Venus of Gagarino (c.20,000 BCE), the Avdeevo Venuses (c.20,000 BCE), and an ivory carving known as the Mal'ta Venuses (20,000 BCE) from near Lake Baikal in Siberia. Magdalenian era art in Russia is exemplified by the Kapova Cave Paintings in the Shulgan-Tash Preserve, Bashkortostan, in the southern Urals and also by Amur River Basin Pottery (14,300 BCE). |

|

|

Bronze and Iron Age Russian Art Almost two thousand years before the Ancient Greeks stunned the civilized world with their architecture, marble statues, pottery, science and democracy, and roughly the same time that British and Irish tribesmen were building their megaliths at Newgrange and Stonehenge (see also megalithic art), Russian goldsmiths and silversmiths in the Caucasus region were creating exquisite metalwork in a variety of precious metals. This Iron Age art is exemplified by the famous Gold Bull of Maikop (2,500 BCE, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg), which was discovered by archeologists in 1897 near the northern edge of the Caucasus mountains. Standing roughly 3 inches high, and made of gold using the lost-wax process, it was excavated from what was believed to be a royal burial chamber. The gold bull and its twin, together with two silver bulls, made up a quartet of animal sculptures which decorated the four supports of a bed canopy. The bull is carefully ornamented with incised concentric circles between its curved horns, as well as lines highlighting the eyes, nose, mouth, hooves and tail. Art historians believe that the Caucasus obtained its artistic know-how and traditions from Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), probably via Lebanon and the maritime trade route into the Black Sea. Fifteen centuries later, that is around 1000 BCE, the Caucasus and Steppes of southern Russia gave birth to the first of several tribal migrations of Celts into eastern and central Europe. Metalworking was a Celtic specialty, although being a practical, semi-nomadic people, they preferred working in iron rather than gold or silver. Indeed it was largely because of the high quality weaponry produced by their blacksmiths, that the Celts managed to establish themselves on the European continent.

Following the decline and fall of Rome in about 450 CE, the centre of Christianity shifted to Byzantium (Constantinople) in present-day Turkey. This Eastern Orthodox Church, as it was known, became the next great patron and sponsor of the arts. When, in 988, Prince Vladimir of Kiev adopted Christianity for himself and his subjects, he too began employing Byzantine architects to build his churches, and artists to endow them with magnificent fresco paintings and mosaic art. One of the oldest and finest is the cathedral of St Sophia in Kiev, planned by St Vladimir and built, between 1020 and 1037, by his son Jaroslav. The cathedral was reconstructed in the style of the Ukrainian baroque, and does not now convey much idea of the original plan, with its five naves. It never, of course, competed with the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople; but with its shallow main cupola, and other secondary cupolas, and its two flanking towers at the west front, it was at that time the finest and richest church built in Russia under Byzantine influence. Most churches were made of wood, which made fresco painting impractical. So instead, religious images were painted on wooden panels (icons), which were typically displayed on a screen separating the sanctuary from the body of the church. This screen, a feature of Byzantine art, eventually evolved into the iconostasis, an elaborate partition adorned with icons. One of the most famous surviving examples of this early form of icon art, is The Virgin of Vladimir (c.1100), now in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. (For more about Icons, see below.) At first, Russian medieval painting followed closely all the developments of the Byzantine. The representations of the Last Supper, for instance, in the conventual church of St Michael in Kiev, finished in 1108, have the same over-elongated figures, with small faces, that are characteristic of Byzantine art at the same period. In the frescoes in the monastery of St Cyril, near Kiev, founded in 1140, the first Slavonic faces appear. Purely Russian elements appear more obviously in the miniature-painting of the period, as soon as it ceased to be practised exclusively by Greeks. There are clear differences; lifelike animal and plant motifs appear together with conventionalized Byzantine faces, and bright reds and blues - always favourite colours of the Russians - emphasize the national character of these manuscript illuminations, which lasted into the thirteenth century. The oldest which can be called truly Russian is the Ostromir Gospel of 1057, but for the time being there was no continued elaboration of a Russian style, for after 1054 the kingdom of Kiev had split up into various independent, and often hostile, principalities. In 1222 the Mongols, under Genghis Khan, seized the Crimea in the south; and in 1237 the Tartars entered into northern Russia, capturing and destroying the cities of Ajasan, Vladimir, Kolomna and Moscow. In 1240 Chernigov and Kiev were taken, and by 1242 Russia had become part of the Mongol empire of the Golden Horde. The Khan of Kipchak, from his capital, Sarai, on a tributary of the Volga, ruled his Russian dominions as a despot. Under this Asiatic rule Russian art was affected by many influences, not, as before, only that of Byzantium. In the great Mongol empire, which, in the second half of the thirteenth century, stretched from the China Sea to the frontiers of Poland, and from the Himalayas to Siberia, the eastern Mongols had accepted Buddhism, and the western Mongols Islam, so that a current of Chinese, Indian and Islamic-Persian art flowed into Russia. Islamic architecture, as the next chapter shows, had taken at about this time - especially in Persia - the sensuous forms which suit the Russian temperament. Four-centred arches, onion-shaped and heart-shaped domes, blind windows, and niche-like recesses, now occurred frequently in Russian architecture, and the new, bright colouring of roofs and cupolas can also be attributed to Asiatic influences. The numerous spires of the churches shone with red, white and green, and there was an increasing tendency to cover them with gold. In cities like Rostov, which were flourishing centres in the time of the Mongols, the Tartar 'Kremlin', or fortified citadel, appeared, and when the Muscovite Grand Duke, Ivan I, moved his capital to Moscow, and in 1333 was confirmed in his dignities by the Great Khan, the first stone-built churches were built in the city, which always, even during the period of Mongol overlordship, tried to surpass all other Russian centres. The Metropolitan now moved his seat to Russia, and the Grand Ducal power established itself so firmly that in 1480 Ivan III was able to free all Russia from the Tartar yoke. In 1453 the Ottomans, under Mahommed II, besieged Constantinople with a great army and a powerful fleet, and in forty days reduced the ancient city, massacred its dignitaries, and made it the capital of the Ottoman Empire. Only in the monasteries of Mount Athos, on the easternmost of the three prongs of the Chalcidician peninsula, in northern Greece, did Byzantine art feebly continue in the hands of Greek and Russian monks. Otherwise, the Byzantine inheritance fell to Russia. By his marriage to the Princess Sophia, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor, who had taken refuge in Rome, Ivan III formed contacts with Byzantium and Europe. It was he who added the two-headed eagle, the badge of the Greek emperors, to St George of Moscow, and styled himself Grand Duke and Autocrat of all Russia. Under him, and his son Ivan the Terrible (Ivan IV), a new Russian empire was created, and with it a national art. Ivan IV, who in imitation of Caesar was crowned as 'Czar', regarded himself as the rightful heir of the Roman and the Byzantine empires. The clergy at once invented an ideology which placed the Czars of Moscow at the head of the new world state: all Orthodox countries were to unite in a single Russian czardom, and the Czar would be the only Christian emperor on earth. No fourth Rome could follow the third, but only the kingdom of Christ, which was eternal. In the legend of Constantine Monomach, who had separated the Orthodox from the Roman church, the majesty of the title of Czar was constantly repeated. Wearing the Hat and Pallium of Monomach, and dressed in brocade and covered with gold, the Czar sits immovably on his throne. Ivan IV was 'Terrible' only to the unorthodox peoples; for the Orthodox Russians he was the stern and god-fearing ruler. Religion became, as it had been in Byzantium, a powerful factor in political life; richly endowed stone-built churches and cathedrals were built in all parts of the country. When the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Holy Virgin, which had just been begun by inexperienced native architects, collapsed, the autocrat summoned the Italian Aristotile Fioraventi from Venice, who built the cathedral, in the years 1475-79, on the lines of the old cathedral of St Demetrius of Vladimir. He gave it, as a foretaste of the new Russian style, five shining onion-shaped domes (the so-called 'imperial roofs') with gilded spires and crosses with chains, while the interior was decorated in the Italian style. He was soon followed by other Italians, among whom were Pietro Antonio Solari, Alevisio Novi and Marco Rufo. Between 1484-1507 they built, at the highest point of the Kremlin, the Cathedral of the Annunciation, while Marco Rufo, about 1487, began the so-called 'Faceted Palace', as the chief residence of Ivan IV. In this way the crystalline fashion of cutting and polishing masonry, known as faceting, first practised in the early Renaissance, was introduced in Russia. In Moscow, in so far as the Italians could influence it, there was a Byzantine Italian renaissance; but in spite of this the interiors of the churches remained in the Russo-Byzantine style, as in the third great cathedral of the Kremlin, that of the Archangel Michael. The well-known Pokrovsky Cathedral (Vasili Blazhenny), at the lower end of the Red Square, was designed by Barma and Postnik. It is not really typical of its period, for such fantastic complexity is an exception; too many things have been crowded in, to produce an effect of the greatest possible magnificence, and no less than eleven chapels are clustered in a disorderly way under the turrets. The only fundamental features of Russian art are the division of the many internal compartments into two storeys, and the replacement of the original wooden gable-roof by pyramidal roofs of stone. Even in the days of purely Byzantine art these abstract forms had proved entirely in accordance with its spirit. A characteristic type of Russian Christian art, the Icon was originally derived from Byzantine mosaics, frescoes and miniatures. The desire to preserve popular legends in permanent form resulted, in Russia, in its development from the Greek image (eikon), and from the icon was developed an original Russian form, the painted screen or iconostasis, which was established everywhere by the fifteenth century. It became the chief ornament of the Orthodox church, assuming the function of the altar-rail, or of the curtain in an Oriental church. Like the proscenium of the Greek theatre, the iconostasis has three doors; through the centre one only priests may go. It divided the holy of holies from the faithful, in much the same way as the rood-screen in the Western church; but it played a much bigger part in the liturgy, and each individual painting on it had a definite meaning. The icon-painters were anonymous monks, whose work, accompanied by prayer and fasting, was itself a form of worship. With great care they prepared their panels of birch, pine or lime-wood, or more rarely, of cypress, scraping a flat surface in the centre, so that the protruding outside edges made a protective frame. The surface was primed with chalk and size, and the colours were mixed with egg yolk in the technique of tempera painting. Strict rules regulated the palette; in early icons the background was gold or silver, but later, white, green and blue were added. As a preservative, the painting was coated with white of egg, which has an unfortunate tendency to darken. The finest icons came from the Novgorod School of icon painting, which escaped the troubles of Mongol rule. When Prince Andrei Bogoljubski besieged the city in 1198 an icon was carried round the walls, and when the image of the Mother of God was pierced by enemy arrows she began to weep; this incident is the subject of the Holy Virgin of Vladimir (c.1131) one of the finest of the many splendid icons in the Novgorod museum. Probably the three greatest Russian icon painters - all trained in the Novgorod tradition of icon painting - are: Theophanes the Greek (c.1340-1410), Andrei Rublev (c.1360-1430) - see his masterpiece the Holy Trinity Icon (1411) painted for the Trinity Monastery of St. Sergius, now in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow - and Dionysius (c.1440-1502). After the Novgorod school, attention shifted to the Moscow school of painting represented by the likes of Procopius Chirin, Nicephorus Savin, and Simon Ushakov (1626-1686). For more about Byzantine-style iconography, see: Icons: Icon Painting. Parsunas: Non-Religious Portraiture Up until the mid-16th century, icon-painters confined their imagery to figures from the Old and New Testaments - notably, Christ, the Virgin Mary, Saints, Apostles and Angels. Then in 1551 Tzar Ivan the Terrible called a Stoglav (religious council), which approved the inclusion of Tzars, as well as legendary or historical figures, within the pantheon of permitted images. As a result, icon-painting widened its scope considerably. A century later, this issue triggered a major schism in the Russian Orthodox Church, but by then the concept of non-religious painting was well established, and painters simply moved onto portraiture, leading to a vogue for Parsunas (from the Latin word persona) - pictures of people similar to icons, but of a non-religious nature. Typically painted on wooden panels, rather than canvas - their emphasis was not on the sitter's character but rather his place/rank in society. An example is the Portrait of Jacob Turgenev* (before 1696, Russian Museum, St Petersburg) by an unknown artist. [*Peter the Great's jester] Russian Art in the 18th Century To help him build/decorate his new capital St Petersburg, Peter the Great lured many architects and sculptors to Russia during the era of Petrine art, such as and also paid for many Russian artists to acquire the necessary skills in foreign Arts Academies. (Others came to Russia of their own accord, like the Italian architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli (1700-71) and Charles Cameron (c.1745–1812). His intention was to set up a special art department in the newly established Academy of Sciences, but death intervened. However in 1757, his successor completed his plan by founding the Russian Imperial Academy of the Arts. Russian painting of the 18th century was dominated by portrait art, one of the few painting genres that made money, and also various forms of folk art. Famous Russian portraitists of the time include: the Italian-trained Ivan Nikitin (1688-1742); the Dutch Realist-trained Andrei Maveyev (1701-39); the formal Alexei Antropov (1716-95); the more decorative, rococo-style Ivan Vishnyakov (1699-1761); the full-blown rococo painter Dmitri Levitsky (1735-1822) - see his awesome Portrait of Ursula Mniszech (1782, Tretyakov Gallery Moscow); Ivan Argunov (1727-1802) patronized by the powerful Count Sheremetyev; the Russian Gainsborough Vladimir Borovikovsky (1757-1825); and the court painter and sfumato expert Fyodor Rokotov (1735-1808). Russian Art in the 19th Century Russian painting of the nineteenth century was strongly influenced by European Romanticism, as exemplified by the romantic portraiture of Orest Kiprensky (1782-1836) - see his Portrait of Alexander Pushkin (1827). Another important figure was Vasily Tropinin (1776-1857), a serf until he was 47, who produced celebrity portraits as well as exquisite genre-paintings - see Lacemaker (1823, Tretyakov Gallery) - becoming a full member of the Academy of Arts in 1824. The realism of Alexei Venetsianov (1780-1847) represented an important step in the evolution of Russian painting. After beginning as a portraitist he turned more and more to genre-painting. Among his contemporaries, the most fashionable portrait painter was the Italian-trained romantic Carl Bryulov (1799-1852) - see Italian Midday (1827, Russian Museum, St Petersburg). Russian history painting (named after the Italian "istoria" meaning story or narrative) was closely linked to religious painting and only broke away from the canons of icon-painting around 1700. However, it didn't come to prominence until the formation of the Academy of Arts, after which it was regarded as the leading painting genre. Early styles were classical in nature, due to the Academy's extreme reverence for classicism. An excellent example is Briullov's The Last Day of Pompeii (1830-33, Russian Museum, Petersburg) which won the Grand Prix at the Paris Salon. Two other noted history painters were Fyodor Bruni (1799-1875) and Vasily Timm (1820-95). Although Russian art had broadened considerably during the 18th century, the Church remained a major patron of the arts, and religious painting was still an important source of influence and revenue. Russian painters who produced major religious (and historical) works, included: the Ukrainian Anton Losenko (1737-73) who became Professor of History Painting at the Academy; and the highly influential Alexander Ivanov (1806-58), whose works included The Appearance of Christ to the People (1837-57, Tretyakov Gallery) a gigantic picture which took 20 years to complete. Authentic Russian landscape painting didn't take off until the early part of the 19th century. Although before this, many artists - including Fyodor Alexeyev (1753-1824), Fyodor Matveyev (1758-1826), Maxim Vorobiev (1787-1855) and Silvester Shchedrin (1791-1830) - had produced a number of masterpieces of landscape painting - these works were very heavily influenced by the Italianate pictures of Lorrain Claude, Poussin and Canaletto. It wasn't until works by Alexei Venetsianov (1780–1847) and followers such as Nikifor Krylov (1802-31) and Grigory Soroka (1823-64), that the real Russian landscape appeared. Meantime, the Italianesque romantic tradition was maintained by Mikhail Lebedev (1811-37) and Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900). The architecture and streets of Russia were also gaining admirers. Andrei Martynov (1768-1826) and Stepan Galaktionov (1778-1854) were dubbed "the poets of St Petersburg" for their atmospheric views of the city's avenues, houses, gardens and quays. Still life emerged as an independent genre in Russia from around 1850. Its finest exponent was Ivan Khrutsky (1810-85), who was greatly influenced by the Dutch Realist masters in the Hermitage Museum. Other still life artists were Kapiton Zelentsov (1790-1845), Alexei Tyranov (1808-59), and Count Fyodor Tolstoy (1783-1873), who excelled at pen-and-ink dawings and gouache miniatures. The Academy's interest in peasant life helped to propel genre-painting onto the curriculum from the 1770s onward. Talented Russian genre painters of the late 18th and early 19th century included: the Russian landscape pioneer Alexei Venetsianov (1780–1847), Yevgraf Krendovsky (1810-53), IA Ermenev (c.1746-1791), and the astute social commentator Pavel Fedotov (1815-52). A minor revolt by some of Russia's most talented art students against the conservatism of the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1863, led to the formation of the Society for Itinerant Art Exhibitions. Seeking to reach out to a wider audience, members of the society (known as peredvizhniki, itinerants, or wanderers) travelled around Russia preaching social/political reform and holding art exhibitions of works completed en route. Leading artists included the genius portraitist and genre-painter Ivan Kramskoy (1837–1887); the stylistically quieter Vasily Perov (1834–1882); the outrageously talented portrait/landscape/genre and history painter Ilya Repin (1844-1930), and the equally stunning history painter Vasily Surikov (1848-1916) - see Repin's Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1883, Tretyakov Gallery) and Surikov's The Morning of the Execution of the Streltsy (1881, Tretyakov Gallery). Other Wanderers included Nikolai Gay (1831–1894) and Grigory Miasoyedov (1834–1911). Many of the Itinerant artists - like Kramskoy, Repin, Polenov and Nikolai Gay (1831–1894) - also painted religious pictures, and did so with a new realism and emotional intensity. Landscape was also a major part of the Itinerants' agenda. Among its greatest exponents were: Feodor Vasilyev (1850–1873); Ivan Shishkin (1832-98) dubbed the "Tsar of the forest" - see his magnificent Oak Grove (1887, Museum of Russian Art, Kiev); the traditional and religious landscape painter Vasily Polenov (1844-1927), the luminous landscape painters Arkhip Kuindzhi (1842-1910) and Nikolai Dubovskoy (1859-1918); and the light/colour expert Isaac Levitan (1860-1900) - see his Secluded Monastery (1890, Tretyakov Gallery). Meantime, itinerant genre painters include Vasily Pukirev (1832-90), Grigory Miasoyedov (1834–1911), Vasily Maximov (1844-1911), Konstantin Savitsky (1844-1905) - see his extraordinary work Repairing the Railway (1874, Tretyakov Gallery), Vladimir Makovsky (1846-1920).

Modern Russian Art - 1890s Onward The Art Scene From 1890 to 1917, Russian art entered a period of both turmoil and creativity. Just as it was becoming really established The Society for Itinerant Exhibitions began to fall apart because of internal dissension. A host of new societies emerged, including the World of Art - founded in 1899 by a group of artists and writers including Alexander Benois, Konstantin Somov, Leon Bakst, Yevgeny Lanceray and Sergei Diaghilev. Much of its subsequent success was due to the remarkable promotional talents of Diaghilev. A rival group, set up in 1903, was the Union of Russian Artists. Other groups included: the Blue Rose, which launched its own magazine The Golden Fleece. Golden Fleece-organized exhibitions in 1908 and 1909 were renowned for the participation of several major French artists. Yet another group, the Knave of Diamonds, staged an important show in 1910, while two Russian avant garde painters - Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) and Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962) staged seminal exhibitions like: the Donkey's Tail (1912), Target (1913) and No 4 - Futurists, Rayonists, Primitives. Although the arrival of abstract painting in the late 1900s caused something of a stir, as it did everywhere, the vast majority of Russian painters during the period 1890-1917 were naturalistic. The former-Itinerant, now World of Art member Valentin Serov (1865-1911) was a brilliant semi-Impressionist portraitist - see his Girl with Peaches (1887, Tretyakov), In Summer (1895, Russian Museum, St Petersburg), Portrait of Isaac Levitan (1893, Tretyakov), and Portrait of Ida Rubinstein (1910,, Russian Museum, St Petersburg). Other Impressionist-style portrait artists included the great Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910) and Konstantin Korovin (1861-1939), while Alexander Golovin (1863-1930), Leon Bakst (1866–1924), Konstantin Somov (1869-1939) and Zinaida Serebriakova (1884-1967) were more classical.

Still life, a genre which fitted well with the decorative and aesthetic philosophy of the World of Art movement, was also popular. Under the influence of post-Impressionists, works became more colourful. Russian still life painters included: Igor Grabar (1871-1960) and Boris Kustodiev (1878–1927), Alexander Kuprin (1880-1960), Yotr Konchalovsky (1876-1956), Ilya Mashkov (1881-1944), Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1878-1939) and the Armenian Martiros Saryan (1880-1972). Russian landscape art was also energized by French Impressionism, notably its plein-air painting techniques. Of those artists already mentioned Valentin Serov and Igor Grabar were consummate landscapists, as was Vasily Surikov. Others included Vasily Baksheyev (1862-1958), as well as Union of Russian Artists members Konstantin Yuon (1875-1958) and Nikolai Krymov (1884-1958). Marc Chagall (1887–1985) produced his own views of the "shtetl" - see View from the Window, Vitebsk (1914, Tretyakov). Rural genre paintings were especially powerful ways of depicting the life of the people. The genre was exemplified by Russian artists like Abram Arkhipov (1862-1930) - see his awesome colourist work Visiting (1915, Russian Museum, St Petersburg); Sergei Ivanov (1864-1910) - see his evocative On the Road: The Death of a Migrant Peasant (1889, Tretyakov); Nikolai Kasatkin (1859-1930) - see his memorable Poor People Collecting Coal in an Abandoned Pit (1894, Russian Museum, St Petersburg). Expressionism was mainly practised abroad. Leading expressionist painters from Russia included: Alexei von Jawlensky (1864-1941) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944). Paris Oct 1906: "Two Centuries of Russian Painting and Sculpture" The year 1906 was a landmark in the history of Russian art thanks to the irrepressible Sergei Diaghilev, the promoter of the giant exhibition of Russian painting at the Autumn Salon in Paris. An impressario with endless energy, Diaghilev turned to Paris to escape the confines of St. Petersburg. His Russian backers, all of them art collectors, included Vladimir Argutinsky-Dolgorukov, Sergei Botkin, Vladimir Girshman, Vladimir von Mekk and also Ivan Morozov, who loaned paintings from his vast collection for the massive Russian retrospective comprising almost 750 works. The exhibition - entitled, Two Centuries of Russian Painting and Sculpture - which opened in October 1906, occupied twelve halls of the Grand Palais of the Champs-Elysee. The interior designs were by Lev Bakst (1866-1924), Diaghilev's most influential artist. Visitors were stunned by the ancient icons laid out on gleaming golden brocades, and by paintings from the Petrine era of Peter the Great and Catherine the Great. Other highlights included portraits by Borovikovsky, Brullov, Kiprensky and Levitsky. But the real point of the show was to showcase modern Russian art by the likes of Isaac Levitan, Valentin Serov, Mikhail Vrubel, Konstantin Somov, Lev Bakst, Philip Maliavin, Nikolai Roerich and Konstantin Yuon. In 1909, Diaghilev - in collaboration with his set designers Leon Bakst and Alexander Benois - launched his most famous venture, the Ballets Russes (c.1909-29), which took Europe and the Americas by storm. 20th Century Russian Abstract Art A number of abstract and semi-abstract movements sprang up in the second decade of the 20th century. All influenced in varying degrees by avant garde ideas coming out of Paris and, to a much lesser extent Milan, they included Russian Futurism (c.1912-14) started by David Burlyuk (1882-1967), later joined by Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930), Velimir Khlebnikov and Alexei Kruchenykh (1886-1968); Rayonism (1912-15) invented by Mikhail Larionov and his partner Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962); Constructivism initiated by Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) - see his extraordinary work Monument to the Third International (1919, Pompidou Centre Paris) - and practised by the painter and photographer Aleksandr Rodchenko (1891-1956), Lyubov Popova (1889-1924), the painter and illustrator El Lissitzky (1890-1941) and Konstantin Medunetsky (1899-1935); and Suprematism (c.1915-1921) founded by Kasimir Malevich (1878-1935). The Russian Revolution 1917 All the above art movements were driven by Utopian ideas, and placed enormous faith in the liberating power of science and technology. As it was, science's first act was to slaughter millions of men in World War I, which triggered the Russian Revolution. Suddenly artistic expression was a political matter, controlled by the Bolshevik Institute of Artistic Culture INKHUK (Institut Khudozhestvennoi Kulturi). Within a couple of years, INKHUK banned easel art and obliged painters and sculptors to switch to industrial designwork. This caused many artists to leave Russia. These emigrants included the expressionists Alexei von Jawlensky, Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall and Chaim Soutine (1893-1953), the sculptors Alexander Archipenko (1887-1964), Ossip Zadkine (1890-1967), the brothers Antoine Pevsner (1886-1962) and Naum Gabo (1890–1977), the Cubist Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973), and many others. After a decade of political argument (1922-32), during which time many 20th century painters and sculptors in Russia abandoned fine art in favour of applied art and design work, Stalin closed down all surviving art groups and decreed the compulsory application of Socialist Realism - a naturalistic style designed to exalt the Soviet worker and his over-fulfillment of the government's 5-Year Plans. The best art museums in Russia include: • The State Hermitage

Museum: Saint Petersburg Phone: (812) 571-34-65, 571-84-46, 710-90-79 • The Pushkin

Museum of Fine Arts Phone: (495) 697-79-98, 697-95-78 • The State Tretyakov

Gallery: Moscow Phone: 8 (499) 230-7788, 238-1378, (495)

951-1362 • The State Historical Museum • The Vladimir and Suzdal Historical,

Architectural and Art Museum For details of European collections containing works by Russian painters and sculptors, see: Art Museums in Europe. |

|

• For more about visual arts in Russia and the Ukraine, see: Homepage. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ART HISTORY |